OUT OF SIGHT

BY SUSAN VAN WYK

Senior Curator, Photography, at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

What is fashion photography? Fashion photography is generally an ideal, not a reality. It is an illusion created with flattering garments and beautiful models. At its simplest, a fashion photograph is an image whose principal function is to show, and sell, clothing; however, fashion photography is not only about the clothes but also about the conventions and the attitudes of the people who wear them. It can be an index to culture and society, to people's aspirations, limitations and taste.

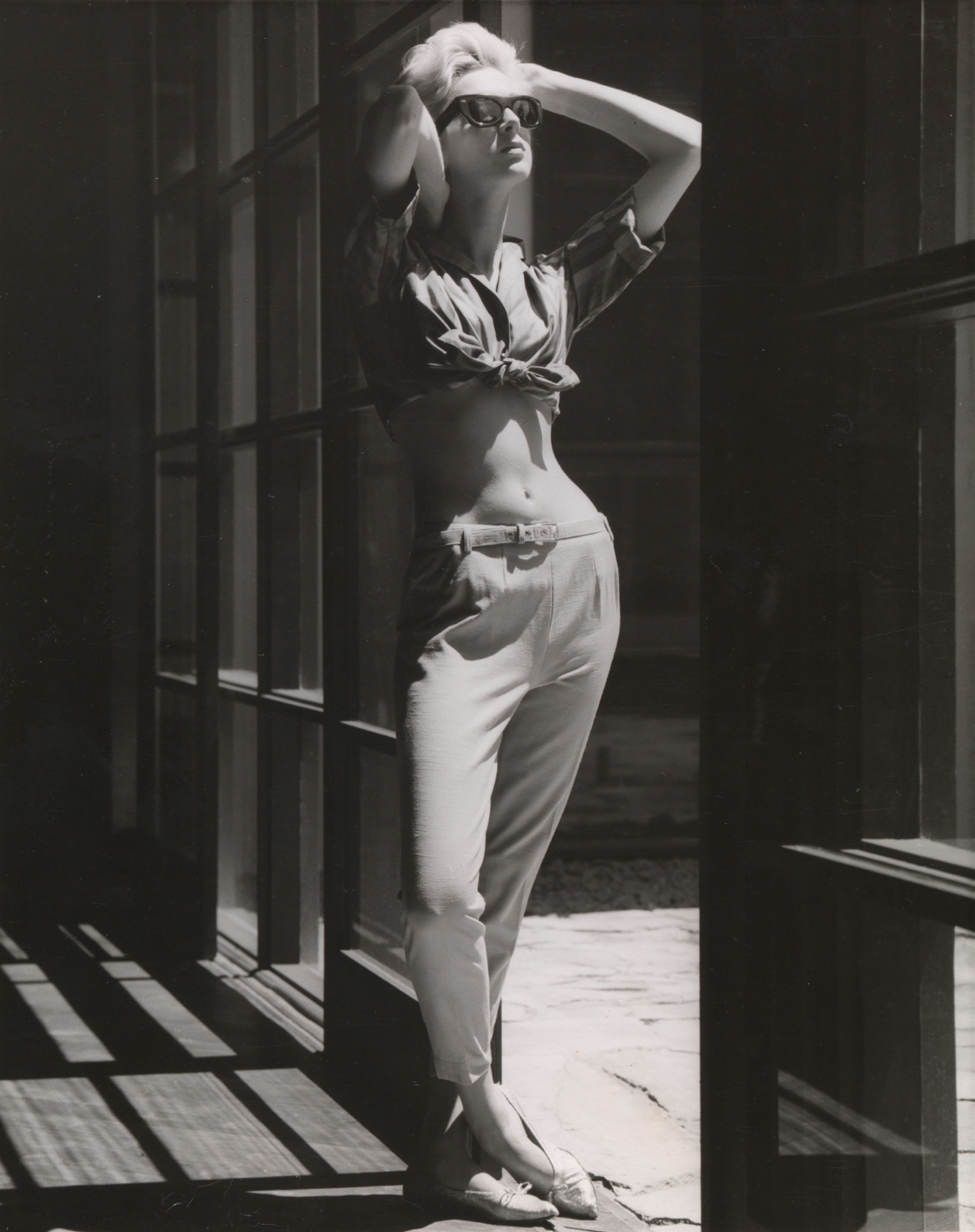

The 1960s was a period of social turbulence when youth-led movements changed the world. In Australia, it was a time of prosperity: employment rates were high and, for many, the opportunities must have seemed boundless. The fashions of the day, including miniskirts and hipster pants, reflected the 'youthquake' that was shaking up the status quo in Australia and internationally. Following the high-glamour fashion photography of the 1950s, studios in the 1960s increasingly started working on location, rather than in the studio, to create images with a fresh, contemporary edge.

Although Henry Talbot began working in fashion photography in the 1950s, it was in the 1960s that he established himself as a leading force in Melbourne's fashion industry. He worked for designers and manufacturers, department stores and boutiques, as well as on the job for the Australian Wool Bureau.1 Like a number of other eminent practitioners at that time, Talbot was an émigré artist who brought the influence of European modernism to Australian photography. Of particular note was his use of 'active' models and outdoor locations which had been pioneered in Europe as early as the 1930s.

Hungarian-born Martin Munkácsi is often credited with pioneering fashion photography using active models, creating images that represented the modern woman and her lifestyle. Munkácsi's works were published in German picture magazines in the 1930s and it is probable that Talbot, as a young design student studying in Reims, was aware of this new way of photographing fashion. In the 1960s Talbot continued to employ such tactics and his work's innovative pairing of contemporary fashion and popular culture captured the exuberant spirit of the times. By the end of the decade he was established as a significant name on the local fashion scene. Talbot's photographs were originally taken for commercial purposes, however, with the benefit of time, the fresh modern look of his work can be seen as exemplifying the emerging youth culture and widespread social changes that characterised the decade.

Establishing a studio

Henry Talbot was born in Germany in 1920, and as a young man studied graphic design and photography at the Reimann School in Berlin. He left Germany in 1939, on the eve of the outbreak of the Second World War, relocated to England and briefly continued his studies at the Birmingham College of Art. Talbot arrived in Australia in 1940 and, following an initial period of internment because he was a German national, served in the Australian army for four years until 1946.2

After the war Talbot relocated to Bolivia, where his parents had settled. Although he recommenced studies in photography and established a successful studio in the Bolivian city of Cochabamba, Talbot was convinced that his future lay in Melbourne. At that time Melbourne was the most important centre of fashion in Australia because of the abundance of textile and garment manufacturers located in Flinders Lane, the many boutiques in the 'Paris End' of Collins Street and the city's major department stores including Georges and Myer.

After his return to Melbourne in 1950, Talbot worked in some of the foremost photographic studios of the day – including Peter Fox Studio and La Trobe Studios where he was a replacement for Hans Hasenpflug – and quickly established a reputation as one of the city's leading fashion photographers. In 1956 he was invited to go into partnership with fellow fashion photographer Helmut Newton, whom he had befriended when the pair was stationed near Albury while serving in Australian Army. By the mid 1950s Newton was renowned locally for his innovative fashion images, and this partnership offered Talbot both recognition for his talent in the field and an opportunity to further establish himself as a dynamic force in Australian fashion photography.3

Newton left Australia in 1957 to work for British Vogue, after which he moved to Paris. He did not return to Melbourne until 1960, and in the interim Talbot ran their studio.4 Talbot credited this as a very influential time during which he was able to learn firsthand about the techniques and trends emerging in Europe. The studio of Helmut Newton and Henry Talbot was a great success, securing major clients including Sportscraft, Fibremakers and the Australian Wool Board.

Vogue Australia

For Talbot and other fashion photographers working in Australia, magazine work allowed greater creative independence than other commercial work did. 'Editorial' fashion shoots enabled photographers to collaborate with fashion editors and stylists, and to create photographs in series rather than single images, as was more often the case in advertising work. Magazine commissions, particularly with Vogue Australia, were highly sought after. Talbot explained:

Unfortunately there are so few Australian fashion magazines in the true sense. It's simply Vogue and Flair who have openings for editorial fashion work here. I mean I'm thinking of occasions when you get a free hand with a collection as compared with fashion work for advertising.5

The arrival of Vogue Australia was hugely important for the local fashion industry as it enabled local designers, such as Norma Tullo and Prue Acton, to have their collections seen by a broad audience. Initially published in 1955 as an Australian supplement to British Vogue, the first standalone issue of Vogue Australia hit the newsstands in 1959. Its inaugural editor was Rosemary Cooper, an English woman who arrived from London bringing the formal 'ladylike' tone of the British issue with her. Cooper was succeeded in 1961 by Joan Chesney, and in 1962 Sheila Scotter was appointed as Vogue Australia's editor-in-chief.6 The importance of working for Vogue, and the calibre of its creative staff at the time, should not be underestimated. Talbot claimed that Vogue's standards were so high that for a single image published in the magazine he would take up to 150 shots.7

Talbot's work for Vogue Australia has an informal sophistication in step with the changing times, and apparently Talbot himself displayed a similar quality. In an interview with Australian Photography magazine, when questioned about his personal style and dress sense, Talbot replied:

Well man this is 1966. And in this game you have to be open to, and live, contemporary influences to a certain degree. The younger generation is very strong in fashion – very much in command. They're spending a great deal of money in the garment industry so fashion is geared to the young. There is, of course, in this 'with it' idea itself, a certain conformity to non-conformity, to a non-conformity standard. But, as a photographer, you must accept this idea as far as you can and that probably reflects to some extent your own behavior and dress.8

Under Scotter's editorship Australian Vogue promoted an ideal of sophisticated elegance; however, some photographers, most notably Helmut Newton, Henry Talbot and Laurie Le Guay, were able to bring a youthful vitality to its pages by working on location rather than in the studio. Beyond being open to current trends, Talbot freely acknowledged the influence of Newton and other photographers on his magazine work. Talbot also admired the work of Richard Avedon, David Bailey, Irving Penn and Bert Stern. Each of these photographers expressed the élan of the times by working on location to create dynamic, 'active' images of modern women. Talbot applied these ideas and made them his own.

Location, Location, Location

There is little an Australian fashion photographer can do that has not been done overseas, and often better. But one thing they do not have is our Australian environment. I use it a great deal because the idea makes it possible to come up with something uniquely different. Henry Talbot9

The locations used by Talbot were an important aspect of his image-making and played a significant role in constructing the narratives implicit in his fashion photography. Talbot's work, like most fashion photographs, presents an aspirational ideal: in his case, a picture of the modern woman. We see her at an opening night; arriving at the airport; on the streets of London; visiting an art gallery; or in a beatnik coffee bar; always wearing the perfect outfit and looking effortlessly up to date and glamorous.

Despite Talbot's assertion that using Australian settings gave his images an edge, some of his most successful photographs artfully disguise the familiar streets of Melbourne. Fashion historian Jess Berry elaborates on this aspect of his work:

While the practice of street photography had been established in international fashion media since the 1940s, the influential working habits of Newton, Talbot and Benini pushed Australian fashion photography beyond studio-based practices concerned with the details of garments, and instead created an 'atmosphere' for fashion staged on Melbourne's street, nightclubs and parks.10

Talbot's use of Melbourne as a backdrop that looked like New York City was a purposeful styling tool used to create a sense of international glamour. In his photograph of a gown by Alouette, Talbot successfully recreated the illusion of New York on the streets of Melbourne: the backdrop, featuring a sports car and city street at night, could just as easily be Fifth Avenue as Bourke Street. The model's confident pose and direct gaze suggest that she is a woman of sophistication and independence.

Similarly, in an image created for Sportscraft around 1961, Talbot successfully created the illusion of a grand garden in London or Paris within the confines of Melbourne's Treasury Gardens. Showing Australian fashion in an 'international' setting was a prerequisite of many of Talbot's Melbourne clients. According to Berry,

Benini, Newton and Talbot were clearly responding to the demands of the market. This is evidenced by the desire of Melbourne boutiques and fashion labels to portray their garments within the aesthetic context of the major fashion cities, as well as the requests of local fashion magazines for photographers to supply versions of their international counterparts ... Benini, Talbot and Newton were able to cast Melbourne in well-established and characteristic roles by alluding to previous iconic images of global cities that had been captured by [Willy] Maywald, [Louise ] Dahl-Wolfe and [Norman] Parkinson in the 1940s and 50s.11

Not all of Talbot's work, however, disguised his Melbourne locations. In his 1961 photo shoot for Melbourne brand Sportscraft, for example, he used an unmistakeably local setting – the banks of the Yarra River at Princes Bridge.

The descriptive caption for this image reads:

Cunningly, Sportscraft emphasises the smoothness of a straight skirt in pure wool... with side buttoning which you can see ... with a Dior pleat at the back which you can't. A Gold Medal winner in the 1961 Australian Wool Awards.12

This suggests that the international styling of the garments shown in a local context was also important to manufacturers, as it positioned Melbourne as a fashion capital.

Talbot also took advantage of atypical locations for fashion shoots across Melbourne. A prime example is a 1966 series of photographs he made set in the Altona Petrochemical Company. In the years leading up to the first manned moon landing in 1969, there was a global fascination with the possibilities of space travel and exploration. In an editorial fashion shoot published in Australian Fashion News, Talbot employed an industrial backdrop to create a futuristic setting.

The series was captioned:

Fibres for fashion's future. Its theme was fibres for the present and the future ... pictures taken by Melbourne photographer Henry Talbot – a man who is as sophisticated as James Bond and always a jump ahead of 'now'. The visiting 'Venusians' in Mr. Talbot's photographs (Maggie Eckardt and Jackie Holme) are gyrating at the Altona Petrochemical Company in Victoria.13

As his reputation grew, Talbot increasingly had opportunities to work on fashion shoots at overseas locations. Then, as now, leading fashion magazines such as Vogue Australia would sometimes select international settings for fashion features. Talbot also worked for the Australian Wool Board who actively promoted Australian wool producers internationally, publishing trade journals and calendars illustrated with photographs of high-end fashion made with fine Australian merino wool.

During the 1960s Talbot worked on assignments in locations as diverse as Papua New Guinea, Hong Kong, India, France and England. In an era when international travel was less accessible than it is today, opportunities to work internationally added to a photographer's cachet. While working on an assignment in Europe Talbot was invited to a party at the prestigious Darien Leigh Model Agency in Paris. Reflecting on this experience, Talbot said,

It's really something for a boy from Melbourne to get the chance of talking with the world's greatest fashion photographers and magazine editors... with our keenness tending to get a little blunted by being so far away from where fashion originates, I found the occasion very stimulating.14

The jet-set lifestyle also played a role as a setting within Talbot's oeuvre. International air travel in the 1960s was relatively expensive and for most people was only a dream.15 Airlines and their handsomely outfitted crews were seen as incredibly glamorous. By using Qantas planes, crews and signature travel bags in his photographs, Talbot was making a link between fashion and the sophistication of the jet set. The use of Qantas imagery was to enhance the status of the garments it was providing an exciting backdrop or context for.

Girls on film: working with models

For Talbot, working with the right model was as important to the success of the pictures as choosing the right location. Like most photographers, he had his favourite models and often worked with Janice Wakely, Maggie Tabberer, Helen Homewood, Maggi Eckardt and Margot McKendry.

Henry Talbot directs models on location at the National Gallery of Victoria 1969

Talbot's philosophy was simple, as he explained:

I've always held that if you can establish a definite emotional rapport with a model you're halfway toward producing good photographs. My own favourite method of fashion working is to explain roughly what I am after then leave the model more or less free to interpret the garment she's to show. A good model will absorb and become part of what she is wearing almost completely. Whilst shooting away I may suggest minor changes, the model senses what I'm after, and then really good shots happen.16

Although he continued to photograph fashion in the studio, Talbot particularly liked to work outside when possible. As he described it, his approach was to

always ... show the models in a free-moving fashion (though not always possible). I avoided stiff (modally) poses... I tried to keep up with what the great fashion photographers overseas were doing. I tried to avoid gimmicks.17

1960s fashion photography can be viewed as reflecting broader social changes for women occurring at the time. Models were increasingly photographed in active rather than passive roles. According to fashion historian Martin Harrison:

Women's fashion magazines were the first medium to present images of women for the consumption of women, rather than men, and the women depicted in these photographs – who after all represented their readers – began to be cast in active as opposed to the passive roles traditionally assigned to them in art.18

The model in action proposes that the modern woman participates in the dynamism of city life, and images of women captured on the move became synonymous with the burgeoning youth culture of the period.

In the early 1960s Talbot was already employing these activation tactics, creating fashion and advertising photographs that sold the ideals of youth, beauty and vitality as much as they sold fashion and products. In the April/May 1963 issue of Vogue Australia, a five-page spread titled 'Moderns on the move' paired the Ford Car Company and the Melbourne garment manufacturing company Pelaco. Model Margot McKendry and swimmer Murray Rose were shown in a series of photographs in which they appear almost bursting with joie de vivre. The advertising copy accompanying Talbot's photographs build further on the narrative:

No matter how whirlwind the schedule our Pelaco Pair never loses their composure. Getting them there calm and collected: a gleaming white Falcon Deluxe Sedan, its trend-setting straight-lined silhouette inspired by the fabulous Ford Thunderbird. Two more assets to any arrival are the shirts they're wearing: His Pelaco Blendene business shirt looks as fresh at midnight as it did at 8 a.m. They're going places, the Pelaco Pair – and riding the crest all the way. They live their life with a style and carefree assurance that many envy. They know and demand the best this modern world has to offer, a personal formula for success that shows in everything they do. You can see it in the clothes they wear (he doesn't own a shirt that isn't Pelaco; she collects Lady Pelaco, secretly feels they were created especially for her). You can see it in the cars they drive – always, a trim, taut, terrific Falcon. With the verve, the confidence, the good taste of these two, any two can be a Pelaco Pair – they could be you!19

Later in the decade, on an international assignment in London in 1967, Talbot produced a series of photographs for the Melbourne firm Sportscraft. London was established as a centre of contemporary fashion and youth culture and Talbot's photographs reflect the 'London look' coming out of the city at that time. In Talbot's image, photographed at Picardilly Circus in London, he again 'activated' his models, placing them among a crowd of young people gathered at the famous landmark. It is not only a successful fashion photograph, showing the garment to great effect, but also an image that captures the spirit of the times.

Across the 1960s, Australian fashion shifted from the more formal elegance that characterised the 1950s to a youthful informality in dress, accessories and manners, and Talbot's photographs trace this transition. His most engaging images were always made on location; he was a master at working on the street and combining garments, models and unexpected elements. His images have a sense of liveliness and energy, and perfectly reflected the 'modern woman' of the 1960s.

- Notes

- 1. From 1953 to 1962 the peak body for Australian wool growers was named the Australian Wool Bureau; from 1963 to 1972 the name changed to the Australian Wool Board; and since 1973 it has been named the Australian Wool Corporation.

- 2. Henry Talbot was among the 1984 German and Austrian refugees deported from Britain in 1940 on the HMT Dunera.

- 3. Helmut Newton is best known for his long career in Europe as an innovative and provocative fashion and advertising photographer. What is less well-known is that he operated a very successful studio in Melbourne that specialised in fashion photography from the mid 1940s until 1961, when he permanently relocated to Paris.

- 4. Helmut Newton's return to Melbourne was short-lived, by 1961 he had permanently relocated to Europe. However, Henry Talbot continued to operate the studio under the name Helmut Newton and Henry Talbot.

- 5. Talbot quoted in Gene Verstraten, 'Henry Talbot: a profile', Australian Photography, Dec. 1966, p. 21.

- 6. Joan Chesney was Australian; Sheila Scotter was born in India, educated in England and arrived in Australia in 1949, aged twenty-nine. Scotter remained editor-in-chief of Vogue Australia until 1971.

- 7. Verstraten, p. 21.

- 8. Talbot quoted in Verstraten, p. 21.

- 9. Talbot quoted in Verstraten, p. 20.

- 10. Jess Berry, 'The metropolis in masquerade: Melbourne through the looking-glass lens of fashion photography', Streetnotes, no. 20, 2012, p. 36.

- 11. Berry, p. 47.

- 12. Typed caption attached to the rear of the photograph held in the NGV Collection.

- 13. Australian Fashion News, March 1967, p. 22

- 14. Talbot quoted in Verstraten, p. 46.

- 15. In 1961 return airfares from Sydney to London cost around £550, equivalent to approximately AUD$14,500 in current dollar terms.

- 16. Talbot in an interview with Anne-Marie Van de Ven conducted in 1995, transcript held in the archives of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney.

- 17. Talbot, interview with Van de Ven.

- 18. Martin Harrison quoted in Hilary Radner, 'On the move', Fashion Cultures: Theories, Explorations and Analysis, Routledge, London, 2000, p. 130.

- 19. Advertising feature in Vogue Australia, April/May 1963, pp. 9–16.