Welcome to the online conservation treatment diary for Nicolas Poussin’s Crossing of the Red Sea. Over the course of this year-long treatment we will be presenting a series of informal updates designed to keep the public informed about the restoration of one of the NGV’s most prized paintings.

Carl Villis has been a conservator of European Old Master paintings at the NGV since 1995. Alongside his primary focus on the restoration process, he likes to participate in interdisciplinary studies involving the technical and scientific analysis of paintings with traditional art history research to resolving unanswered questions about works of art.

An introduction to the project

The main aim of this diary is to provide you with the opportunity to look in on the many steps required to bring such a treatment to completion. Large scale conservation treatments can take months, sometimes even years. They require patience, discipline and planning. We hope the real-time release of news about this treatment while it is in progress will enable you to experience something of the journey the painting and the conservator take as the treatment unfolds.

What does the term “conservation treatment” mean? Broadly speaking, the treatment of paintings falls into two main categories: structural and superficial. Structural work involves the repair of components of the picture which can no longer properly serve their physical function, such as a canvas that is torn, a panel which is split, or paint layer which is flaking.

Superficial treatment concerns work to the surface of the painting, for example the removal of old varnish and restorer’s overpaints, the application of a new varnish, and the retouching of lost or worn areas of paint. Both structural and superficial treatments are time-consuming and demand a ongoing process of adjustment and decision-making to reach the best balance between the demands of the artwork and its material condition. The Poussin treatment will mainly involve surface work.

Any canvas painting as old as the Crossing of the Red Sea – which we know was painted around 1634 – is bound to have its share of conservation issues. Few paintings emerge unscathed even after a century. For that reason, and also on account of its size, a full year has been set aside to complete the restoration and return the painting to the Gallery walls.

This is the first time we have undertaken an informal online record of a major treatment like this, so it will undoubtedly take time for us to exploit this medium, but we shall try at the very least to accompany the written posts with photos and where possible, with audio-visual content.

Map of treatment

Examination

Examination of the painting takes place before conservation treatment commences. In this process all available information about the condition and manufacture of the painting is recorded and assessed. It usually involves a number of imaging techniques such as x-radiography and infrared reflectography which provide additional information not detectable by the naked eye. Examination is a step which is ongoing throughout the conservation treatment.

Photography

The painting is photographed many times throughout the conservation treatment: Before treatment, after varnish removal, after re-varnishing, during retouching and after completion of the treatment, and several times in between those stages. Additionally, it is photographed in many other ways: under UV light and under raking light. Photography is considered one of the fundamental forms of documenting an artwork.

Scientific

Throughout the year the Crossing of the Red Sea will undergo scientific analysis. Microscopic paint samples will be examined to learn more about the materials Poussin used for this painting. In particular we will analyse his pigments and binding materials. This part of the project will be carried out with CSIRO Australia.

Technique

Throughout this treatment we will learn more about how Poussin painted this picture: how he planned, what stages he had to go through to get the final result, and what revisions he made along the way.

Cleaning

The cleaning of the Crossing of the Red Sea will involve the removal of old varnish and retouchings left by previous restorers. This will take place in two or three stages once the preliminary examination is completed.

Retouching

Retouching, also called inpainting, will be the most time-consuming part of the Poussin conservation project. This is done only on areas of the painting which are lost or worn. Although the painting is in acceptable condition for its age, it has nonetheless suffered some surface wear and tear which needs to be addressed.

Varnishing

The painting will be given new layers of varnish at varied stages of the treatment. The first – applied with a brush – will take place after the old varnish and retouchings are removed. Further selective brush applications may be needed at later stages, depending on how well the varnish covers the paint. The last will be done by spray gun after the retouching is complete.

Research

Because technical examinations often uncover new information, conservation treatments are often perfect opportunities for research into the painting. This can cover broad areas of historical, scientific or technical investigation relating to the artist or the painting.

Re-installation

When the conservation of the painting is complete the painting will return to display on the walls of the National Gallery of Victoria and will be reunited with its frame, which is considered a masterpiece of French eighteenth-century decorative art.

Getting Started

No conservation treatment ever begins by getting straight into the physical act of cleaning or repairing the picture. It is always preceded by a phase of looking, learning and recording. These simple-sounding steps are some of the most important things a restorer needs to do to ensure a successful outcome to a treatment. They are also continuous from the beginning to the end of the job.

The amount of time needed before treatment can begin will depend on the amount of information available about the work and complexity of the problems the painting presents.

Looking

Paintings are objects created expressly for looking and contemplating. Understanding the painting as an image left to us by the artist is the first part of the conservator’s duty. Equally important is the need to assess the painting as a physical object on its journey through history. Time can cause permanent changes to the look and structure of a painting, so it is therefore essential for the conservator to be aware of these changes. A thorough examination enables the whole process to take place from a foundation of knowledge and sensitivity to the requirements of the painting.

The work needs to be observed from all vantage points: up close, from a distance, and under different lighting conditions; with the naked eye, the magnifier and the microscope. There is also much to be learnt from examining the sides and the reverse of the picture. A lot of hidden information is contained there which can reveal its history.

Learning

The learning takes place with the aid of examination, surveying the relevant historical literature, conservation research and records and online sources. Discussions with curators, conservators, scientists and art historians are also important in understanding the breadth of issues surrounding the painting.

Recording

The recording is done with documentation, photography, scientific analysis, radiography, infrared reflectography and any number of analytical tools available to the conservator. All of this material is compiled and retained in the department’s records for reference, and is eventually fed into the wider body of conservation research.

When a painting is as old and significant as the Crossing of the Red Sea, there will inevitably be extra information to absorb. Over the past few months we have been able to bring the picture to the NGV conservation studio to familiarise ourselves with it and the literature surrounding it.

Like many regular visitors to the Gallery I looked at the painting for decades in awe of its imposing grandeur and its flow of bodies and colour, but I have also been able to observe it for a long time from the conservator’s critical perspective. It is one of the privileges (and perhaps one of the curses) of conservators that they are able to see in an artwork not just what history has left to us, but also what it has taken away. With Poussin generally, and with Crossing of the Red Sea in particular, it is critical to know that the painting in its present state does not appear as it did in the seventeenth century. There have been considerable changes to the picture, some of which are irreversible.

In the next few posts we will look more closely at some of these things we have learned about the painting.

Pentimenti

Though we are rarely able to perceive it with our own eyes, paintings are always in a state of transition. Scientific and technical analysis can enable us to understand how the materials used by the painter have aged over the years. It can also shed light on the path of transition the painting took while Poussin was still at work on it: the alterations he made to parts of the picture to bring it to completion.

It is not uncommon to find artist-made revisions to paintings, even when the painter has laid out a detailed preparatory drawing on the unpainted surface. These revisions, more commonly known aspentimenti, can even be found in the work of painters such as Jan van Eyck and Raphael, who were renowned for their careful planning, while there have been many others – foe example the sixteenth century Italian painters Andrea del Sarto and Dosso Dossi – who often made radical changes midway through the painting process, with the finished work ending up substantially different from its original intended appearance.

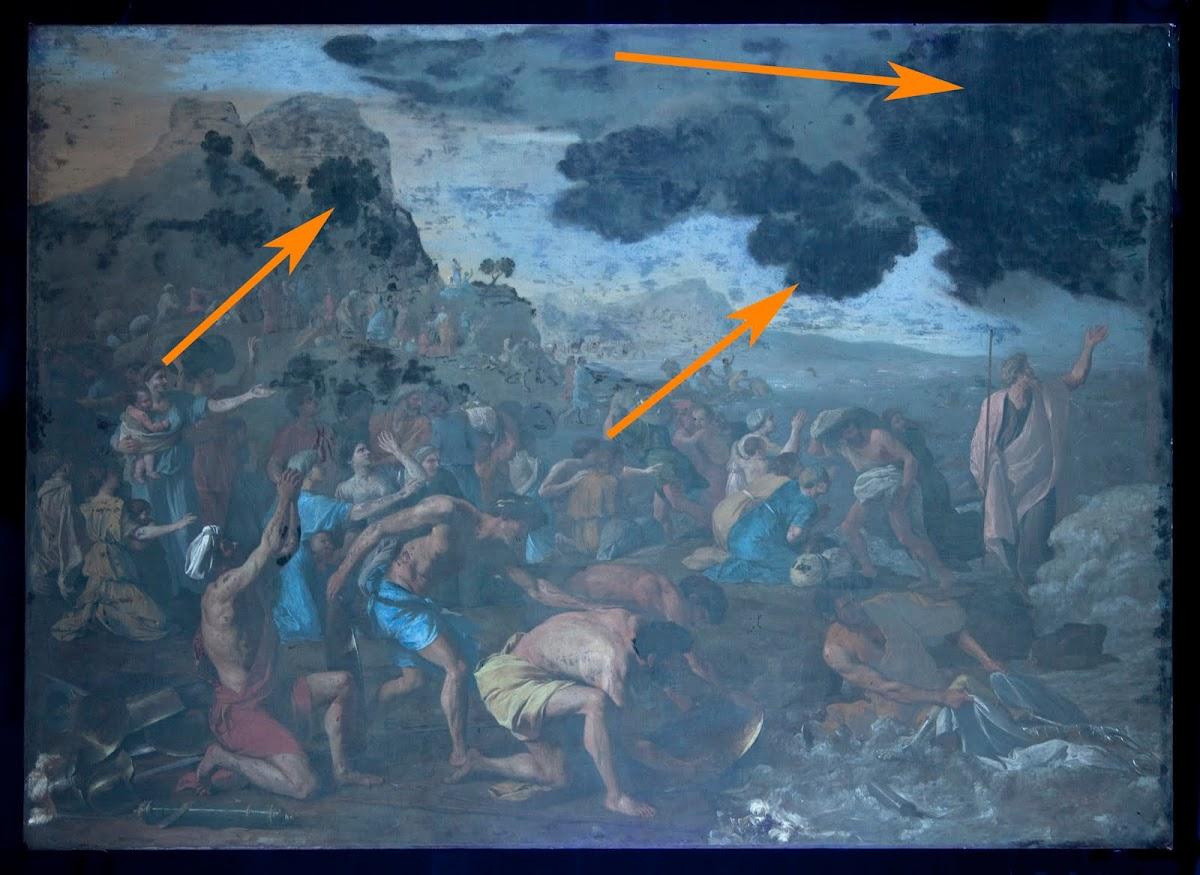

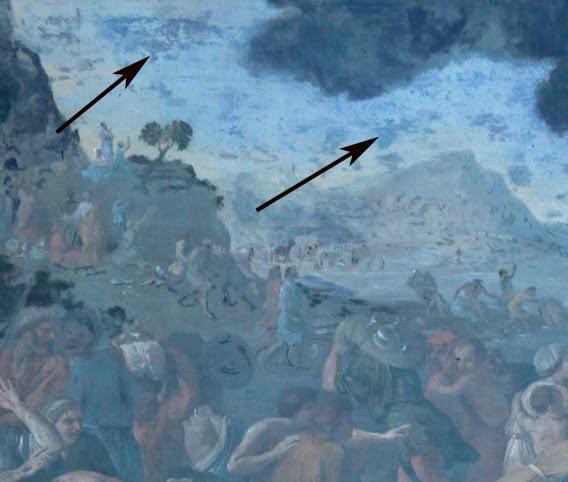

A pentimento in the landscape

Poussin’s preparatory technique was famously rigorous and highly planned, yet he too frequently made adjustments as he went along. The Crossing of the Red Sea is full of changes to both the landscape and the figures.

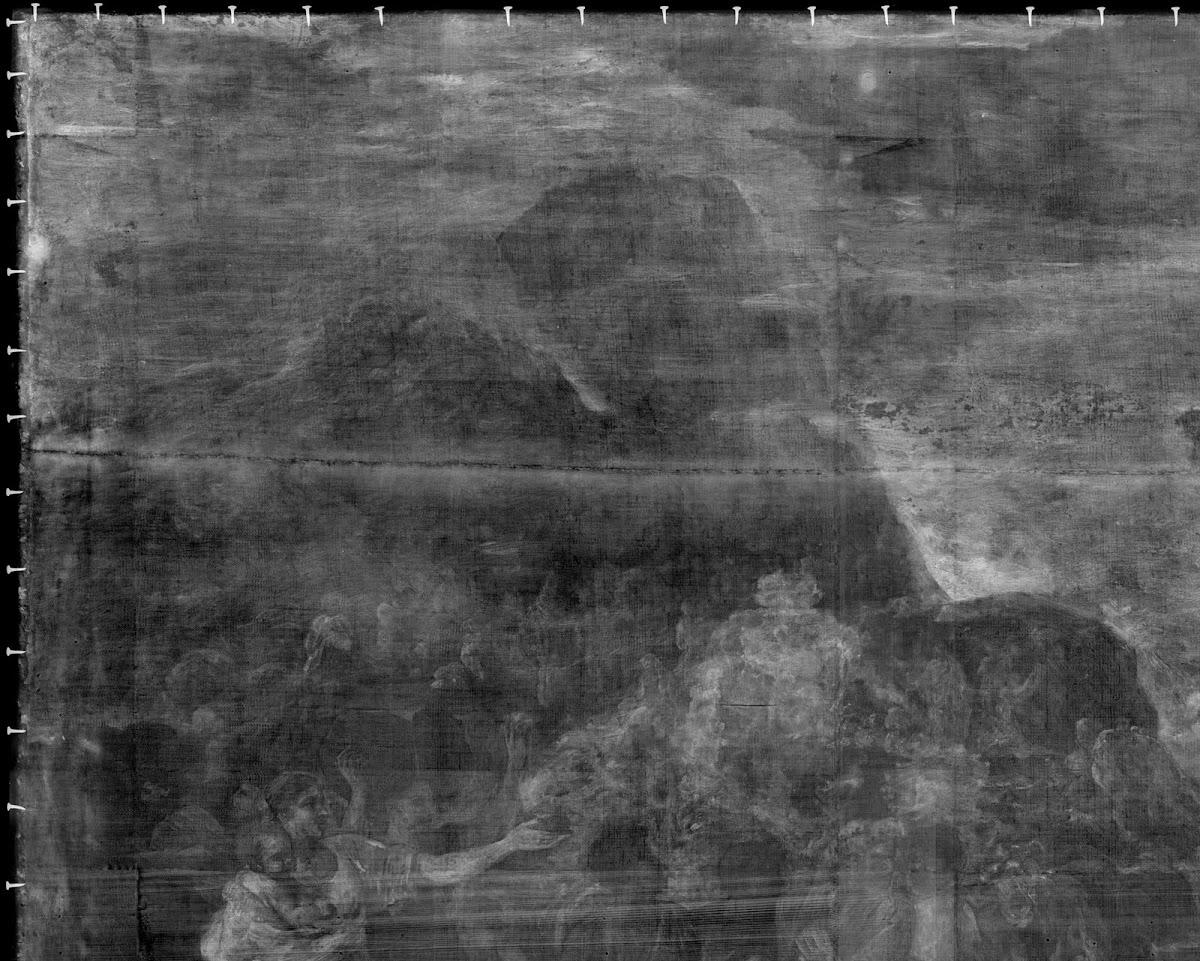

The upper photograph shows the top left corner of the painting. The lower photo is the x-radiographic image for the same area. The radiograph, or shadowgraph as it was once more descriptively called, reveals that Poussin seems to have originally planned for just the one tall mountain peak.

The dark areas of the radiograph are not caused by dark paint, but rather by the absence of the x-ray-absorbent paler pigments which were used for the sky. When laying in the paint of the sky Poussin painted around the area he intended for the mountain, and the area he left unpainted was the space he left for his intended mountain. The radiograph suggests that when he painted the left peak he had to paint over an area originally intended to be sky.

Pentimenti in the figures

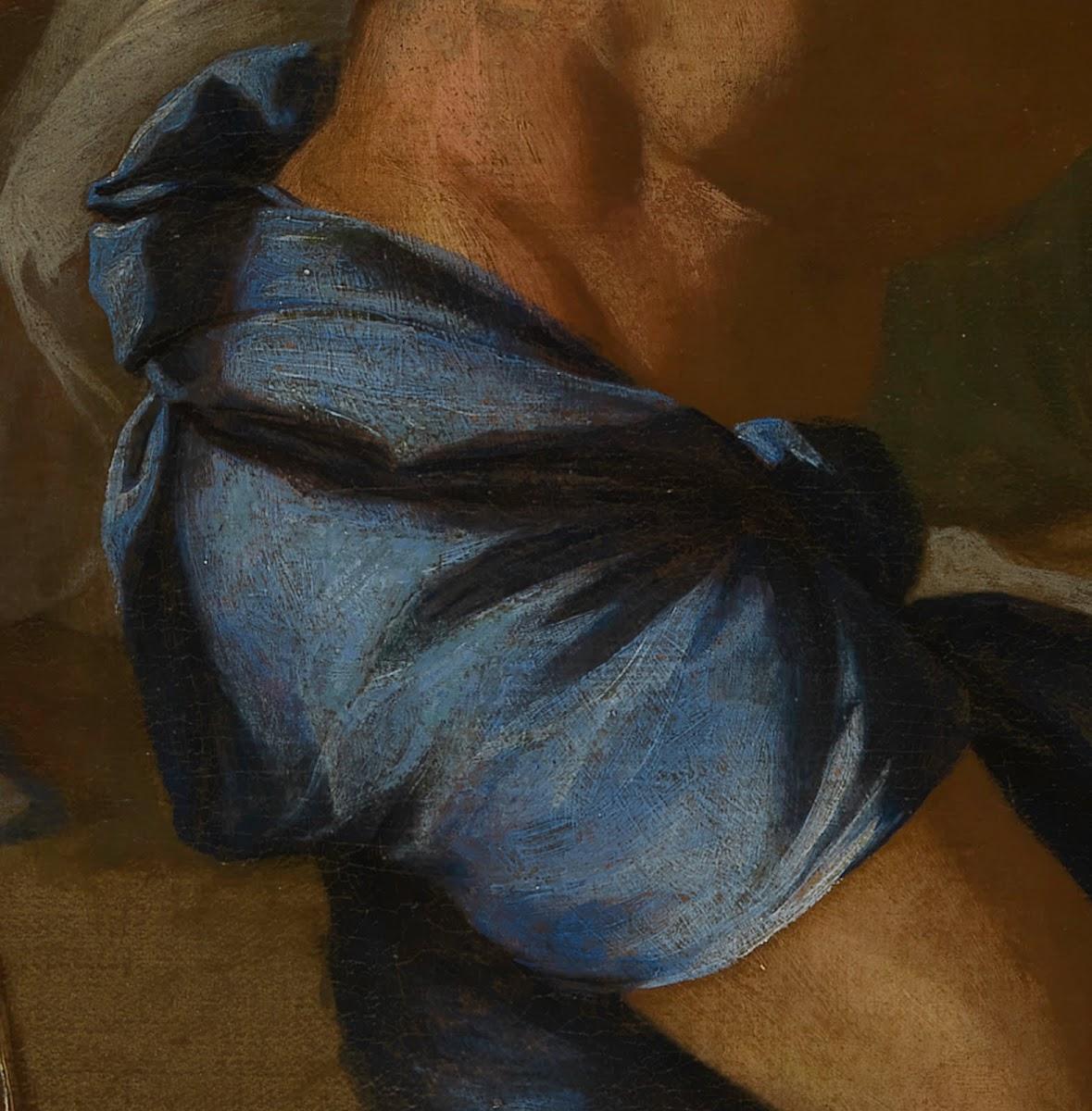

Another type of pentimento common to Poussin is the addition of draperies to figures he first painted nude. The three primary figures of the painting were all painted nude and were “clothed” after the figures were complete. This was not done out of prudery but as part of his process to create harmony of groups of figures by arranging them first in their most elemental form, unencumbered by heavy clothing. In the following images you can see a detail of the central figure and its corresponding radiograph.

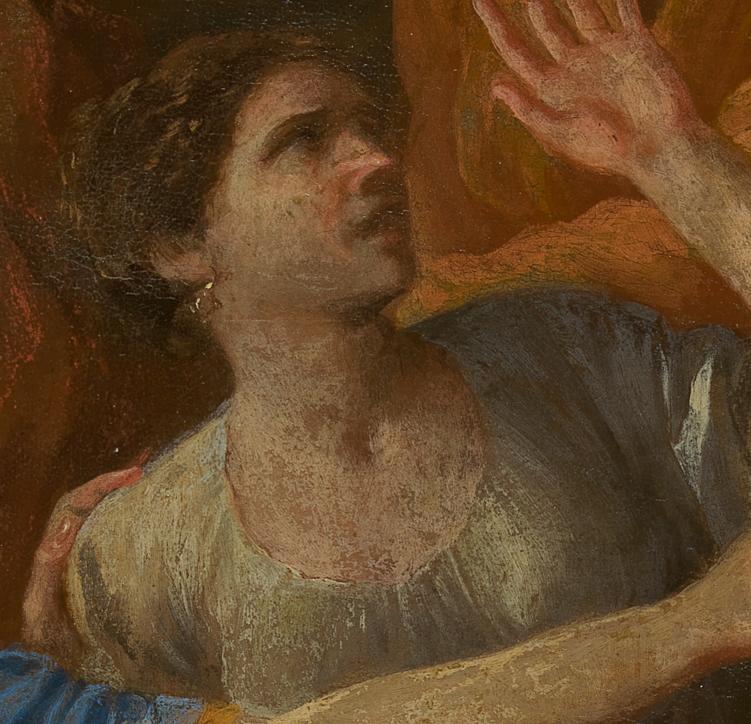

The naked form of the figure is clearly visible in the radiograph, with the streaky brushstrokes of the upper leg and hip visible beneath the almost horizontal brushstrokes of the blue drapery. Finally, there are plenty of smaller pentimenti scattered throughout the picture which are visible to the naked eye, such as in the headscarf of this female figure below. For some reason Poussin decided to extend it down further than he originally painted it, so he was obliged to cover part of the head of a background figure, with the ear of the male figure visible beneath.

In the next post I will show you some of the changes to the painting that have been brought about by the passage of time.

Some changes in the painting

Because many paintings survive for generations some may think they are resistant to the effects of time. This is not so. Paintings age much like people, albeit at a slower rate. While they both might retain their essential features over time, their appearance changes markedly from their youthful prime. Certain parts change colour, wear out or fall away; overall shape changes, surfaces become worn and creased. Without constant maintenance both become increasingly fragile.

Pigment Change

We can be sure the Crossing of the Red Sea does not look the way it once did. All paintings are affected by the passage of time, in both structure and appearance. There is one aspect of change in Poussin’s work which has been frequently commented on: a shift in the painting’s tonal values. By this we mean that the visual balance between the light and dark tones seems to have changed over the centuries. The belief is that many of Poussin’s paintings are darker in appearance than they once were as a result of the increasing transparency of some of his pale pigments and the artist’s technique, with his paint applied in rather thin layers.

It is quite possible that the water washing against the shore in the lower right of the painting is less prominent than it once was, and that the earth colours of the foreground shore area are also darker than originally intended. Several pigments are known to change appearance over time: some blues can turn black, others turn grey, some greens can change to brown. The blues in the Crossing of the Red Sea appear much darker than the same blues seen in a seventeenth-century replica of the painting, but for the moment we cannot quantify this change. Scientific analysis later in the year may help give us some indication about how much change has taken place.

Knowing about these types of changes can help us get a more informed understanding about Poussin’s intentions and can perhaps steer us away from any misconceptions which might otherwise arise.

Changes in the painting’s structure

There are other changes in the painting which are not apparent to the general viewer.

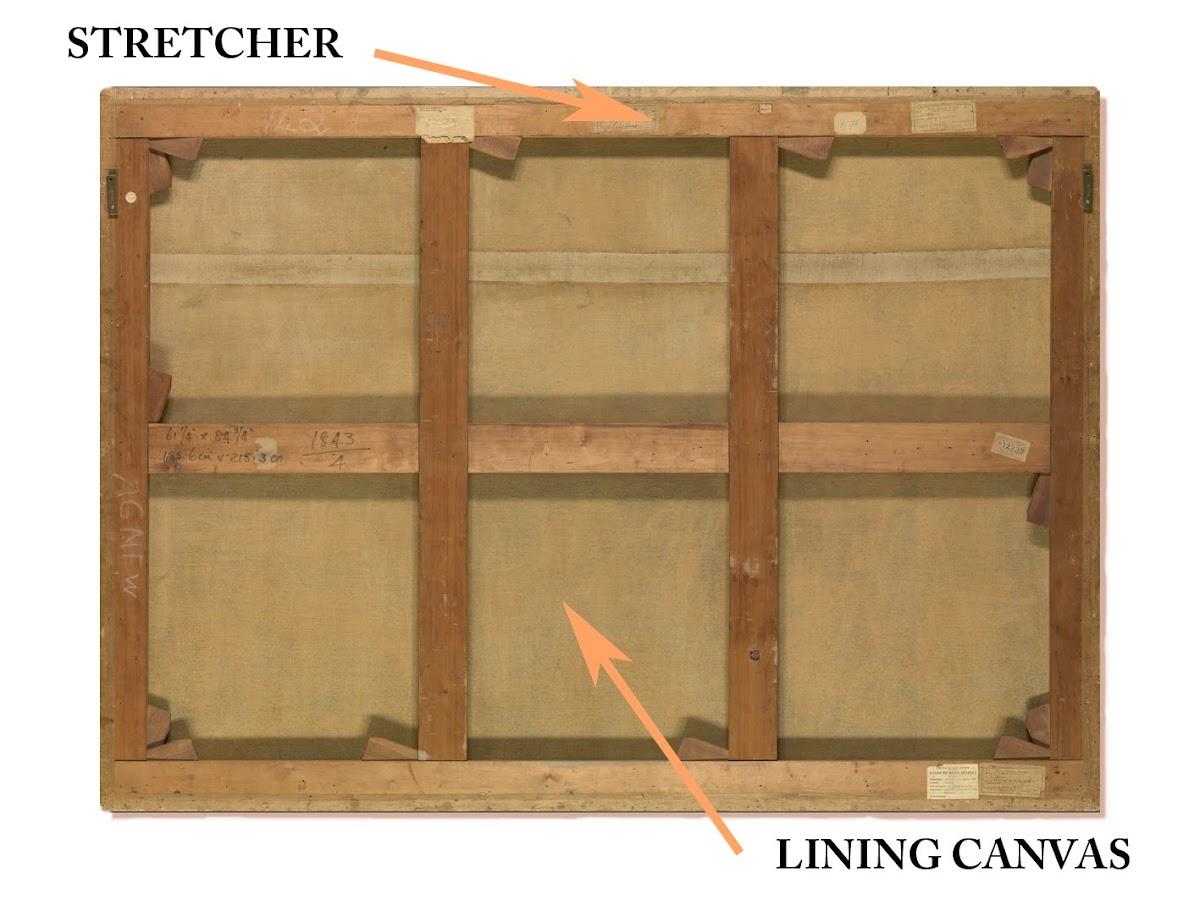

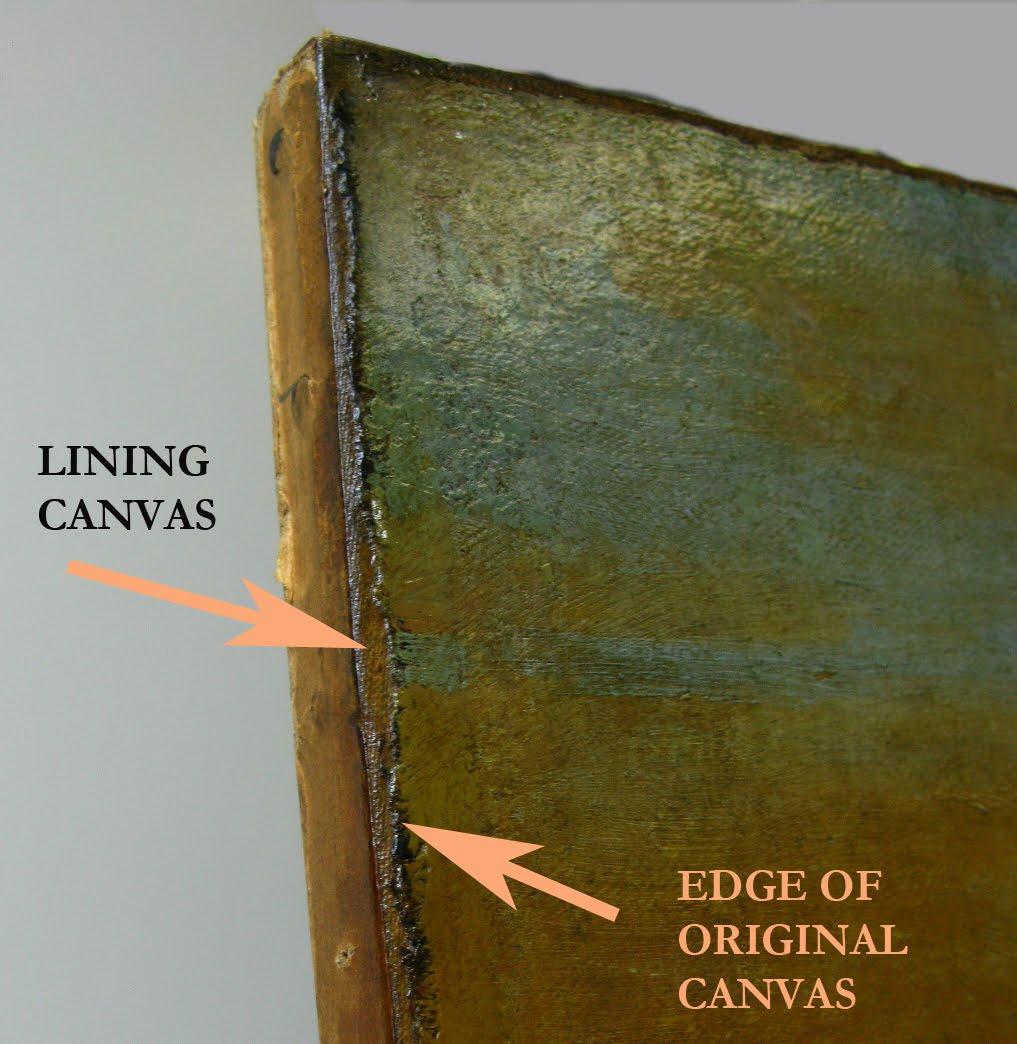

This photograph shows the reverse of the Crossing of the Red Sea. No visible part of it is original to the painting. The wood stretcher which holds the canvas probably dates from the second half of the nineteenth century. Stretchers are replaced when the previous one is damaged or inadequate to support the weight and shape of the picture. It is quite possible that the stretcher it replaced was also not Poussin’s original.

The canvas visible on the reverse also probably dates from the nineteenth century. This is a lining canvas, which was bonded to the back of the original to give it greater strength and the rigidity needed to prevent the paint and priming layers from breaking up.

The thin horizontal strip of canvas in the upper part of the reverse is an additional piece of canvas added to provide further rigidity over the seam of a join in the original canvas. Poussin’s original canvas is made up of two pieces of canvas sewn together – as we will see in a later x-radiograph. With time and movement, the join line has caused a horizontal crack line visible from the front of the painting, so the strip was applied over the reverse of the lining to prevent further weakening of this vulnerable area.

A detail of the top left edge of the painting.

The photo above shows how the original unpainted edges of the canvas have been trimmed, so that the painting is held onto the stretcher only by the lining canvas. We always check this feature during the examination to determine whether the painting has been cut down. If the original edges are intact, then we can say that the painting retains its original proportions. Sadly, it is not uncommon to find paintings which have been cropped into a smaller size. Though the edges of the Poussin have lost their original unpainted edges, we know by other means that there has been no cropping of the painted surface. In the next post we will look at how the painting was x-rayed.

Exodus 14

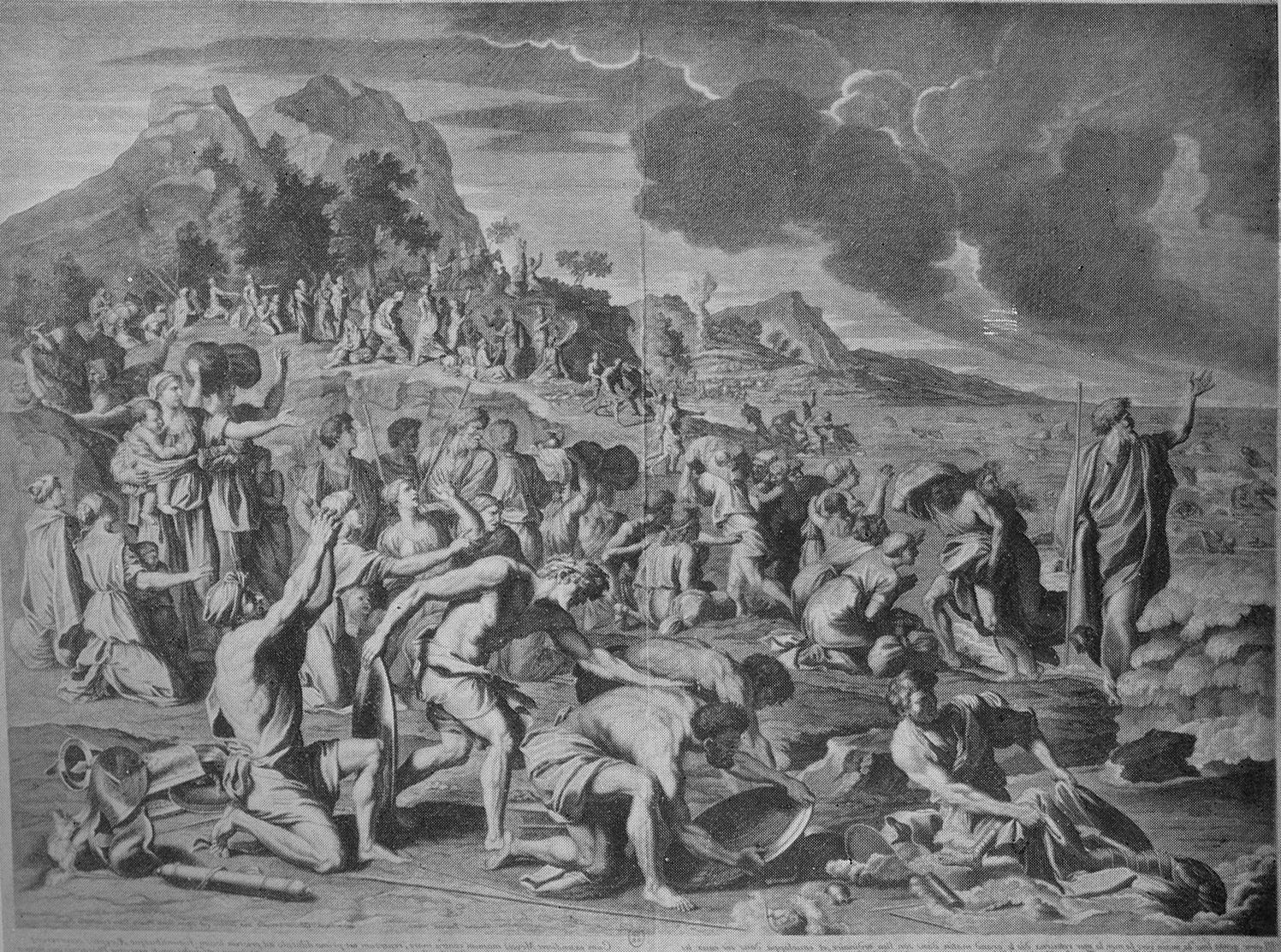

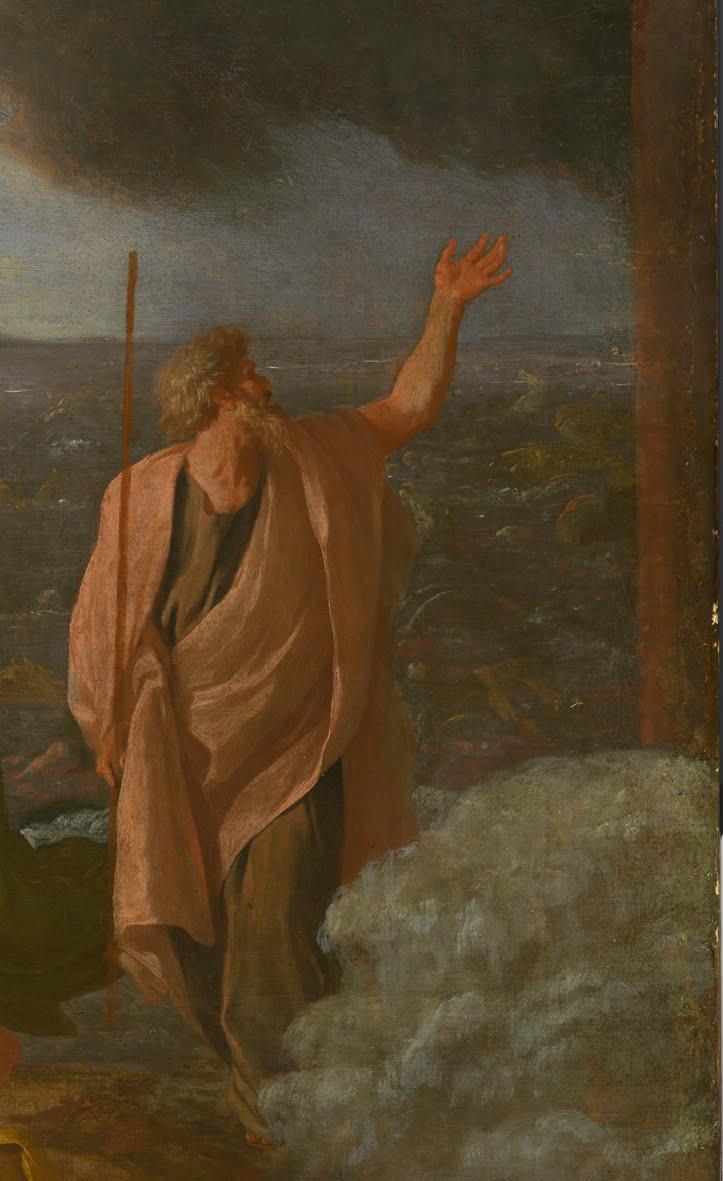

Moses stretching his hand out over the sea to close the water over Pharoah’s men. The “pillar of fire” is at the right edge of the painting.

Exodus 14 is the source text for Poussin’s Crossing of the Red Sea. This highly cinematic passage of the Old Testament provides a wealth of details and scenes for narrative painters to draw on, and it is clear that Poussin studied it closely when he began devising his version.

For many people, the Crossing of the Red Sea is memorable for the scene of Moses’ miraculous parting of the waters before the Israelites began to head out from the shore. However, in Poussin’s time the theme was more often depicted a later stage of the story, with the Israelites safely back on shore and the pursuing Pharoah’s army drowned after the waters had closed in on them.

Though Poussin also chose to use this same part of the story, he referred closely to the text for guidance on how to describe the scene. In the painting you can see Poussin has taken note of Moses’ carrying a staff (16) and holding his arm outstretched (27). The painter also included the “pillar of fire” (24), and drowned Egyptians upon the shore (30). The “pillar of fire” is a detail which is not not commonly found in many previous interpretations of the story by painters such as Bronzino, Mazzolino and Cosimo Rosselli.

Here is the text:

Exodus 14

1 Then the LORD said to Moses, 2 “Tell the Israelites to turn back and encamp near Pi Hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea. They are to encamp by the sea, directly opposite Baal Zephon. 3 Pharaoh will think, ‘The Israelites are wandering around the land in confusion, hemmed in by the desert.’ 4 And I will harden Pharaoh’s heart, and he will pursue them. But I will gain glory for myself through Pharaoh and all his army, and the Egyptians will know that I am the LORD.” So the Israelites did this.

5 When the king of Egypt was told that the people had fled, Pharaoh and his officials changed their minds about them and said, “What have we done? We have let the Israelites go and have lost their services!” 6 So he had his chariot made ready and took his army with him. 7 He took six hundred of the best chariots, along with all the other chariots of Egypt, with officers over all of them. 8 The LORD hardened the heart of Pharaoh king of Egypt, so that he pursued the Israelites, who were marching out boldly. 9 The Egyptians—all Pharaoh’s horses and chariots, horsemen and troops—pursued the Israelites and overtook them as they camped by the sea near Pi Hahiroth, opposite Baal Zephon.

10 As Pharaoh approached, the Israelites looked up, and there were the Egyptians, marching after them. They were terrified and cried out to the LORD. 11 They said to Moses, “Was it because there were no graves in Egypt that you brought us to the desert to die? What have you done to us by bringing us out of Egypt? 12 Didn’t we say to you in Egypt, ‘Leave us alone; let us serve the Egyptians’? It would have been better for us to serve the Egyptians than to die in the desert!”

13 Moses answered the people, “Do not be afraid. Stand firm and you will see the deliverance the LORD will bring you today. The Egyptians you see today you will never see again. 14 The LORD will fight for you; you need only to be still.”

15 Then the LORD said to Moses, “Why are you crying out to me? Tell the Israelites to move on. 16 Raise your staff and stretch out your hand over the sea to divide the water so that the Israelites can go through the sea on dry ground. 17 I will harden the hearts of the Egyptians so that they will go in after them. And I will gain glory through Pharaoh and all his army, through his chariots and his horsemen. 18 The Egyptians will know that I am the LORD when I gain glory through Pharaoh, his chariots and his horsemen.”

19 Then the angel of God, who had been traveling in front of Israel’s army, withdrew and went behind them. The pillar of cloud also moved from in front and stood behind them, 20 coming between the armies of Egypt and Israel. Throughout the night the cloud brought darkness to the one side and light to the other side; so neither went near the other all night long.

21 Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and all that night the LORD drove the sea back with a strong east wind and turned it into dry land. The waters were divided, 22 and the Israelites went through the sea on dry ground, with a wall of water on their right and on their left.

23 The Egyptians pursued them, and all Pharaoh’s horses and chariots and horsemen followed them into the sea. 24 During the last watch of the night the LORD looked down from the pillar of fire and cloud at the Egyptian army and threw it into confusion. 25 He jammed the wheels of their chariots so that they had difficulty driving. And the Egyptians said, “Let’s get away from the Israelites! The LORD is fighting for them against Egypt.”

26 Then the LORD said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the sea so that the waters may flow back over the Egyptians and their chariots and horsemen.” 27 Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and at daybreak the sea went back to its place. The Egyptians were fleeing toward it, and the LORD swept them into the sea. 28 The water flowed back and covered the chariots and horsemen—the entire army of Pharaoh that had followed the Israelites into the sea. Not one of them survived.

29 But the Israelites went through the sea on dry ground, with a wall of water on their right and on their left. 30 That day the LORD saved Israel from the hands of the Egyptians, and Israel saw the Egyptians lying dead on the shore. 31 And when the Israelites saw the mighty hand of the LORD displayed against the Egyptians, the people feared the LORD and put their trust in him and in Moses his servant.

THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2010 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

X-raying the Poussin

Paintings have been examined by radiography ever since x-rays were first discovered by the German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895. Today, over a hundred and fifteen years later, there is still no more useful tool for the conservator than radiography because it can provide information about so many components of the painting. Other valuable examination tools, such as infrared imaging or microscopy tend to be more specific in their application.

At the NGV, paintings in the collection are routinely x-rayed as part of the documentation process carried out by the conservation department. The process is usually straightforward but must be carried out according to strict health and safety regulations. Paintings are laid out onto a special lead-lined table containing the x-ray unit. Once the painting is in position large photographic plates in lightproof envelopes are placed on the surface, then covered with a lead-lined cover to ensure that the hazardous x-rays are safely contained. The unit is activated for a short time – like a camera shutter exposing the photographic film -causing the x-rays from the unit to pass through the painting and onto the x-radiographic plate. Once the plate is exposed it is then taken to the x-ray processor for developing. With larger paintings many plates are required to get the whole work radiographed. The Poussin needed thirty separate plates.

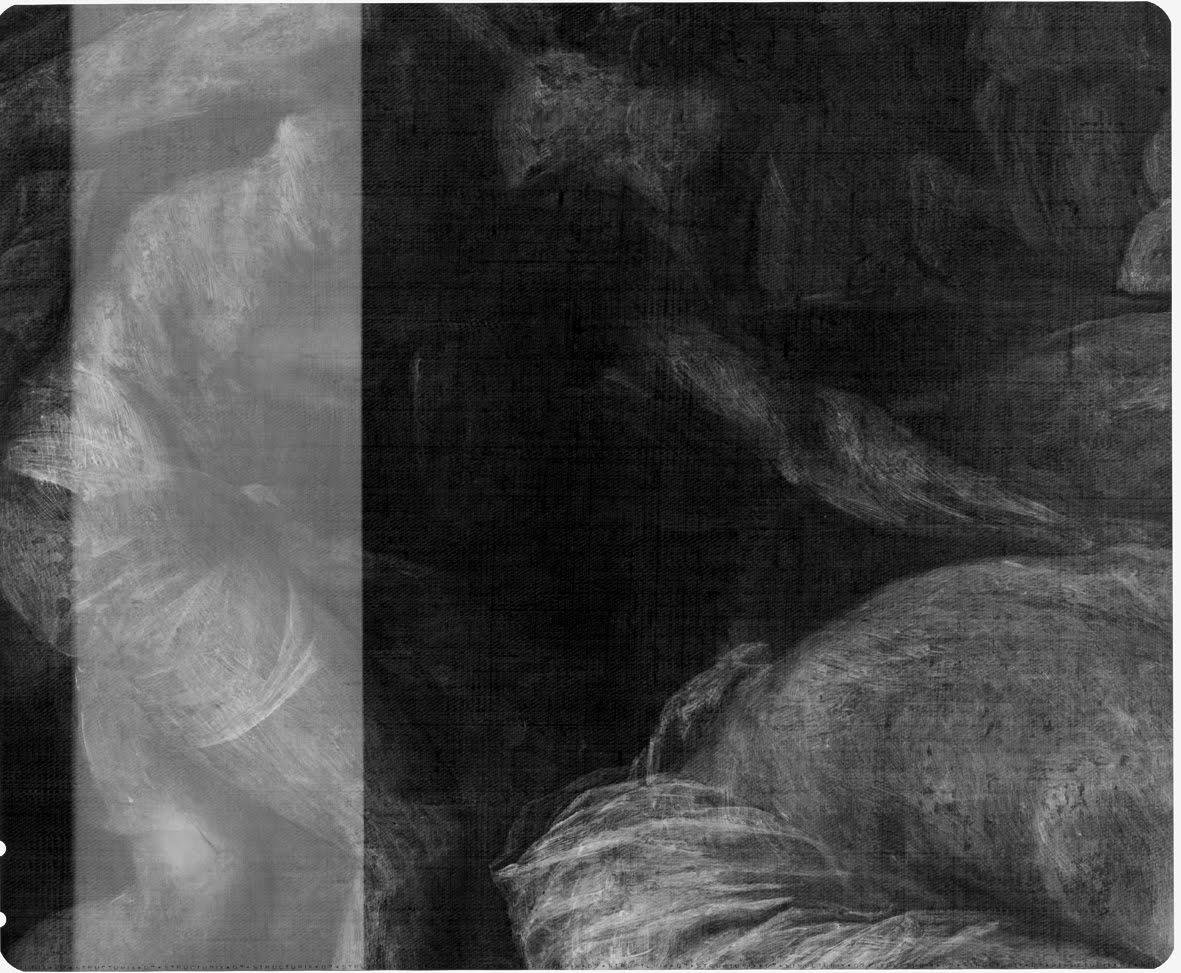

This is what a single plate looks like once it is processed. To get the most value out of the technique it is usually preferable to join all the other plates together so that the image for the whole painting can be read in one go. In the past this used to be done on large light boxes, but it is now done with digital imaging technology. To do that, each plate is digitally scanned. The scanned images are then assembled on a computer, using imaging software to form a large composite image.

The above image is the digitally assembled radiograph for the painting. It reveals not just the painting on the canvas but also the wood stretcher and all the other components which hold the work together. Radiographs can be very useful for determining the condition of those structural components, particularly for paintings on wood panels. However, there are other times when the image of the stretcher can impede our examination of the painted surface. In these cases we are able to digitally adjust the radiographic image to reduce the effect of the stretcher, as we see in the image below.

Now we are able to recognize the image of the painting and can make some assessment about the artist’s technique. The fact that the radiograph corresponds with the painting as we normally view it tells us that Poussin did not make wholesale changes to the painting while he was at work.

We saw in the earlier post about Poussin’s modifications that some of the smaller changes – such as adding clothing to naked figures – were visible in close up details of the radiograph, but on the whole no large scale alterations are present.

On some paintings radiographs will reveal radical changes or even an earlier painting underneath the final image. Here is an example: In this detail of a painting by the eighteenth-century painter Joseph Wright of Derby you can see another face. This is from a much older portrait which sits beneath Wright’s.

We will return to the Poussin radiograph throughout the year as questions about different parts of it come into focus, whether they concern the materials or technique or damage. In the next post we will look at the painting under ultraviolet light.

A strategy for cleaning

With the documentation and examination of the painting now well underway, the time has approached to develop a strategy for cleaning the painting, that is, the removal of the discoloured varnish and restorer’s overpaints. While every cleaning must follow the particular demands of each individual painting, the steps we will take for the Crossing of the Red Sea are typical for the treatment of many old master paintings.

Before cleaning can commence, tests will need to be carried out to ensure that it can be done with the minimum of risk. Here are some of the steps we’ll take:

Tests under magnification

The first stage will involve testing of the solubility of the varnish and potentially the paint films. During an examination it usually clear what type of varnish lies on the surface and what type of paint medium has been used by the artist. With that knowledge a suitable varnish removal solution is selected and tried out on a tiny area of the surface of the painting, usually near an edge. This is generally done with the aid of a magnifier or microscope to see how the varnish and paint respond to the cleaning solution. If problems occur the choice is clear: stop or otherwise find another an alternative cleaning mixture, or perhaps a different method of cleaning. In most cases, when the varnish and paint layers are properly understood it does not take long to arrive at a suitable method.

Small windows on different areas of the painting

Once the cleaning tests indicate that the old varnish can be safely removed, the next stage in the process will involve carrying out slightly larger tests in different passages of the painting. The aim of this part of the process is to determine how the cleaning solution works in different parts of the painting.

The surfaces of paintings are not uniform in their composition; certain traditional pigments – for instance lead white – often form stronger and more resistant paint films than others, such as vermilion red or azurite blue. Other colours might be more vulnerable because the artist may have added a resin (similar to the varnish medium) to the oil paint medium, making it potentially vulnerable.

Furthermore, some parts of the painting might contain a different paint medium altogether: In the seventeenth century it was customary for some painters to use a medium other than the usual linseed oil for specific pigments. It was not uncommon for blues to be painted with walnut or poppy oils, which were less prone to yellowing than linseed. Other painters used a glue-like medium for blues. Investigations into Poussin’s materials have shown that he generally used linseed oil but did employ walnut oil for some blues and occasionally added pine resin to his paint. For this reason, all potentially vulnerable areas of paint need to be tested. Once this has been done it will be time to commence the removal of old varnish and restorer’s overpaints.

With testing out of the way it is now time to commence the varnish removal. It comes as a surprise to some people to learn that the cleaning can be a relatively quick part of the restoration process. With the Crossing of the Red Sea we have anticipated that the cleaning time required will take up only one month of the twelve we have set aside for the treatment, though that will be subject to revision if we encounter any unexpected problems.

Like the testing, the varnish removal itself will take place in stages:

First stage of varnish removal

If the solubility tests suggest the cleaning will not present any particular problem, the first part will involve a first broad cleaning across the painting. The aim of this step is to remove the bulk of the discoloured varnish and restorer’s retouchings, leaving fine residues and hard-to-remove retouchings for a later secondary cleaning. Doing it this way gives you an opportunity to assess the cleaning in a gradual and considered way and allows for adjustments to be made you go along. For example the conservator can vary the proportions of the solvents used as it the varnish thins down.

Second pass of varnish and overpaint removal

The second pass allows the painting to be cleaned to a more refined level of consistency across the surface and allows for any problematic areas to be cleaned on their own terms. Quite often older restorer’s retouchings were painted in oil, making them more difficult to remove. Removing them during a second stage of cleaning enables them to be treated locally.

Mechanical removal

Sometimes old retouching paint and varnish is resistant to solvent cleaning. When this occurs, they may need to be cleaned mechanically. This is often done manually with the aid of a scalpel, delicately scraping or chipping the non-original components away from the original. This is almost always done under magnification, either with a magnifying loup or else under a stereomicroscope. It can be very time-consuming.

Final Balance

The later stages of cleaning are about ensuring that the painting has been cleaned to a consistent level of finish. Throughout the process the conservator ought to have developed a clear idea of what he or she wants to achieve with the cleaning and what is the best that can be reached given the variables involved: the condition of the original paint layers; how vulnerable they may be to the cleaning solution, the feasibility of removing the varnish and overpaints, the aesthetic implications of removing the non-original components, and so on.

Ideally the final balancing stage of cleaning provides the opportunity for final subtle adjustments to be made to reach the appearance required.

The revelations of UV photography

As we draw closer to the cleaning of the Crossing of the Red Sea we turn our attention to UV photography. A quick glance at an image of the painting under ultraviolet light is enough for a conservator to learn some of the critical issues regarding its surface, especially the condition of the old varnish and the previous restorer’s work.

When paintings are placed under UV light they fluoresce in a particular way which looks very different to their appearance under normal lights. Apart from the overall bluish tone it gives to the picture, we can often perceive a slightly milky layer blanketing the colours and tones. This effect usually comes from the varnish layers. Old tree-resin varnishes such as dammar or mastic typically fluoresce a pale green colour, and this becomes more pronounced as the varnish gets older. The fluorescence visible on the UV image of the Crossing of the Red Sea is what one would expect to see in a fifty-year old varnish.

However, what is more notable about this photo are the very dark patches which interrupt this overall pale effect. They are indicated with the arrows in the photo below:

These dark areas are patches of retouching applied by Horace Buttery – the previous restorer – in 1960. The extent of dark areas of the clouds and trees tell us that he needed to do quite a lot of work in those areas, suggesting that the underlying original paint was damaged or worn some time earlier.

When we look at a detail from the UV photograph we can see that there are also considerable smaller retouchings in the sky which are not visible under normal light:

These old damages and repair are not uncommon in canvas paintings as old as the Crossing of the Red Sea , so are not cause for alarm. What they mean in terms of the treatment ahead is that the cleaned painting will reveal the wear and tear the painting has endured, and that the upper part of the painting will require more work to reintegrate than the lower part containing the figures, which is in a better state of preservation.

Previous restorations

Has the Crossing of the Red Sea been restored before? Certainly. You could say that most Old Master paintings have been cleaned at least once during each century of their existence, so it is quite possible that our painting has been cleaned at least four times.

Do we know when and how it was cleaned? Not entirely. The thorough documentation of conservation treatments is a rather recent phenomenon. Only a handful of art museums around the world have concise records of treatments carried out before World War II, and many do not have much in the way of reporting before the 1960s. For works in private collections, conservation records have been almost non-existent.

Consequently, trying to trace the conservation history of an old painting like the Crossing of the Red Sea (which remained in private hands until 1948) inevitably becomes an exercise of searching for clues within the picture rather than looking around for information from files and correspondence.

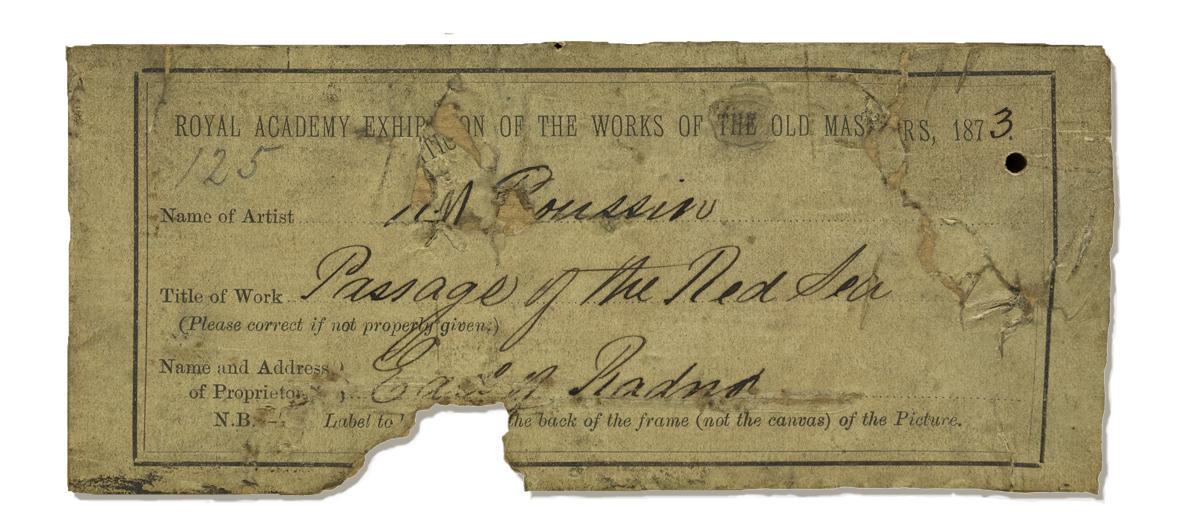

Nevertheless, we do have some information on the painting’s previous restorations. It was cleaned in London in 1947 by an as-yet unknown restorer while still in the collection of the Earl of Radnor. It was cleaned again by the pre-eminent restorer Horace Buttery in 1960.

Buttery had an illustrious career in London from 1929 to 1962. For decades he cleaned paintings for a large number of England’s most important galleries and dealers, and eventually served as picture restorer to the British Royal Collection. During this period the NGV occasionally sent some of its most valuable paintings back to London to be restored by Buttery, most famously with Giambattista Tiepolo’s Banquet of Cleopatra in 1955.

The curious decision to have the Crossing of the Red Sea restored again so soon after the 1947 cleaning will be explored in a later post, however it is likely that the decision to send the painting to the major Poussin exhibition at the Louvre in 1960 was the catalyst in prompting NGV Director Eric Westbrook to send it to Buttery. The decision appears to have been made in concert with the National Gallery in London, where the pendant Adoration of the Golden Calf was concurrently restored by Herbert Lank. The two cleaned paintings were hung side by side at the National Gallery in 1961 following the Paris exhibition.

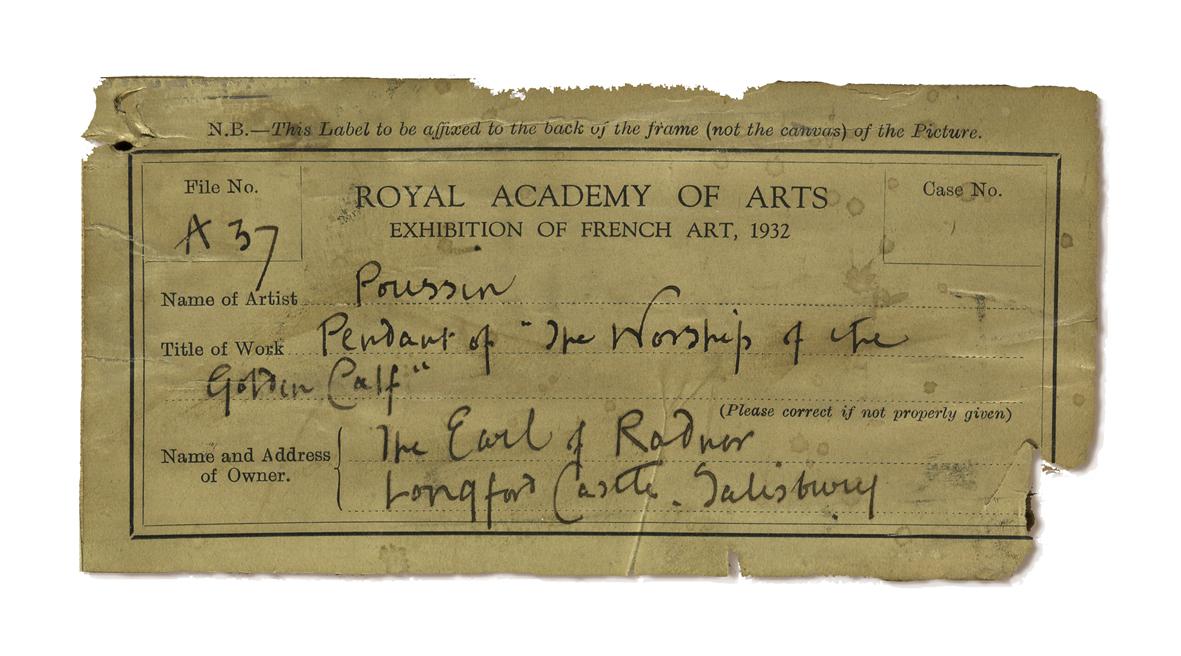

We do not have any documentation from Buttery, but we can trace his work by examining the painting. His treatment was largely confined to cleaning and retouching. He did not do any significant structural work on the painting. Certainly, he did not line the painting or fit its current stretcher: there are labels on the reverse from Royal Academy Exhibitions of 1873 and 1932, indicating that the painting was lined and fitted with its current stretcher some time before 1873.

The Royal Academy Exhibition label from 1873

The Royal Academy Exhibition label from 1832

We will have to wait until the painting is cleaned to see if there is more to learn about the treatment history.

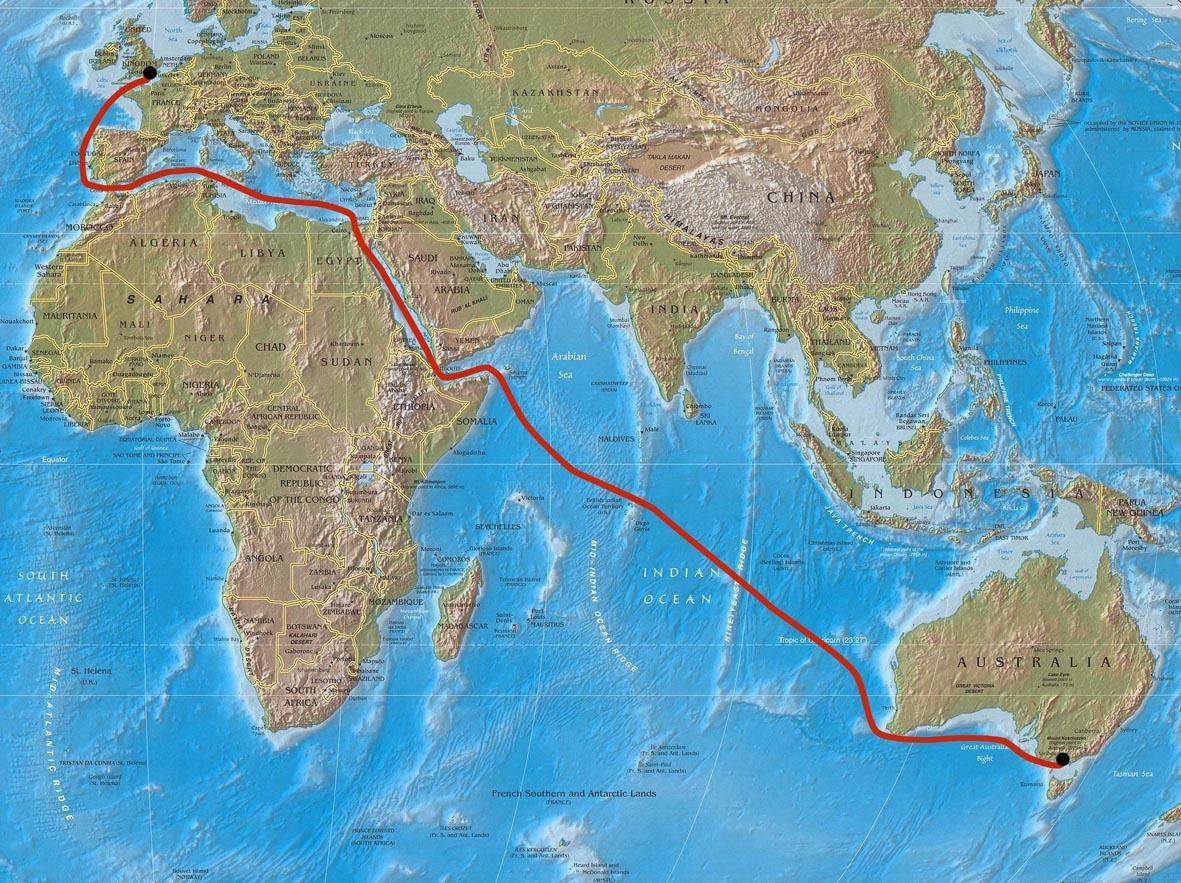

Crossing the Red Sea—literally!

It is a delightful quirk of fate that Poussin’s Crossing of the Red Sea has actually crossed the Red Sea – three times in fact.

Originally painted in Rome for a collector in Turin, the picture’s long journey took it to France and eventually England, where it stayed for two centuries before it was acquired by the NGV in 1948.

To get here it had to travel by ship, taking the route from London through the Mediterranean Sea and eastwards to the Suez Canal. From there it passed through the Gulf of Suez down through the Red Sea and onwards across the Indian Ocean. The route of the biblical crossing made by Moses and the Israelites is not known. The Old Testament does not provide locations which are known to us today, so we can only speculate which path they are said to have taken, but we can be sure it was not the long north-to-south route taken by our painting as it headed out to Melbourne.

The painting made a return journey to Europe via the same route in 1960 when it went back to London for conservation treatment and then for exhibition in Paris before its final sea journey back to Melbourne. The painting will almost certainly never pass through the waters of the Red Sea again, as it would now be transported by air.

Removal of varnish and old retouchings

Cleaning tests had revealed that the old varnish – applied by Horace Buttery in 1960 – could be removed using standard cleaning solutions without risking Poussin’s paint surface. So what do we mean by a standard cleaning solution?

Well, first it depends on the type of varnish being removed and the vulnerability of the underlying paint. Critical to the ability to safely remove varnish from most paintings is the condition that oil paint is different to varnish resin in terms of chemical structure. We can exploit this difference by selecting solvents which affect the resin without breaking down the structure of the oil.

For many Old Master oil paintings covered with a traditional varnish such as dammar, paintings conservators will frequently use a blend of an “active” solvent, such as acetone or possibly isopropanol, with a “diluent” solvent such as mineral spirits. The diluent solvent has the effect of controlling the solubilizing of the varnish by the active solvent; essentially, it slows down the rate of removal, allowing the conservator to work in a measured way.

If the paint layer underneath the varnish proves to be highly vulnerable with these types of organic solvents there are other cleaning systems available to the conservator. However, the vast majority of pre-1800 paintings are cleaned with solvent mixtures. For the Crossing , a solution of one part acetone to one part mineral spirits was used for the first pass of cleaning, in which the bulk of the varnish was removed. For the second pass, the amount of acetone was reduced, and for the third stage of scalpel removal of old restorer’s retouchings, only mineral spirits were used to help wipe away the debris.

The three main stages of cleaning were completed in about a month. This proved to be relatively straightforward as there weren’t many layers of older varnish and retouchings to remove. Clearly, Buttery had cleaned the painting thoroughly in 1960. Poussin’s thin and smoothly applied paint surface also aided a quicker varnish removal; where artists have applied paint in thick and textured brushstrokes there is a greater likelihood that old varnish will become lodged in the recesses of the textured paint, and over time these old residues can discolour and become harder to remove.

The visual impact of the varnish removal was appreciable, but not dramatic. Certainly not as stark as this recent cleaning of a sixty-year-old varnish we undertook from Giambattista Tiepolo’s & nbsp Finding of Moses :

With the Poussin, the most visually striking thing about the cleaning was not the removal of the varnish but of the old retouchings. As we had anticipated, the dark clouds on the right side of the painting were worn right down to the priming layer:

Above: the painting before treatment.

Here is the painting after removal of the varnish and old retouchings.

In addition to these we also noted the full extent of another type of old damage to many of the areas of flesh-coloured paint. Several of Poussin’s thinly applied skin tones displayed numerous small pit-like losses, leaving the surface looking broken and with less definition:

Above is a detail of one of the figures before treatment.

Here is the same detail after removal of old varnish and restorer’s retouchings

The enlarged detail above shows just how many of these losses there are in the surface, creating a visual chatter which makes it hard for the eye to read Poussin’s original brushwork.

With the varnish removed the full extent of the work which lies ahead has been revealed. The painting needs to be revarnished, and then inpainted in the areas which have suffered the most damage. In areas such as the clouds, a considerable amount of inpainting will be required to mask the damage and reconcile them with the best preserved passages, so that the painting displays a consistent level of surface condition.

Using copies to learn about lost information

When Horace Buttery cleaned the Crossing of the Red Sea in 1960, he encountered a painting which had suffered surface damage from previous cleaning attempts.

He knew his job would be to reconcile the well preserved parts of the painting with those areas which were permanently affected by paint losses and abrasion to the surface, particularly in the sky. He was faced with the task of trying to recover some of the lost appearance of that crucial component of the painting. It is possible, but not likely, that he had access to copies of the painting that were made in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

These copies could have provided him with some help in retrieving certain details which were now lost from the original.

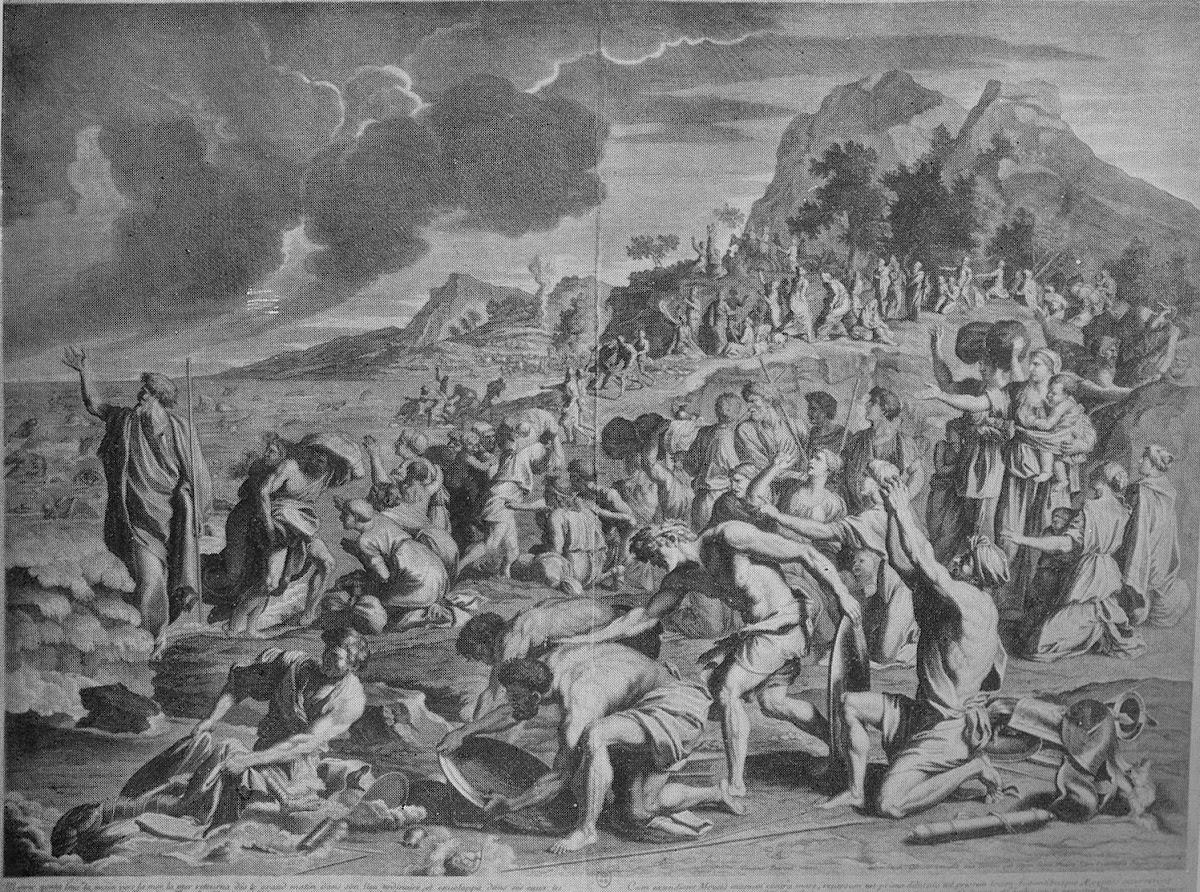

Crossing of the Red Sea was copied a number of times during the sixty years (c1680-1741) it was held in Parisian collections, a testament to the reverence in which the painting was held by French artists and collectors. Buttery might have known that the image was turned into an engraving by the French artist Etienne Gantrel (1646–1706).

The original engraving shows Poussin’s image in reverse, for Gantrel copied the image first onto a copper printing plate which would then be used for printing copies onto paper. Seen this way it is at first hard to make a direct comparison with the painting, so with the benefit of digital imaging we can flip the engraving to match the composition of the original:

Gantrel’s version of the clouds with details of lightning appears to be supported by the other version of the painting which Buttery may have known about: the tapestry made of the painting by the Gobelins Tapestry workshop between 1684 and 1691:We can see that Gantrel’s engraving closely follows Poussin’s original with one notable exception: the pillar of fire at the extreme right edge of the image has been omitted. More about this in a later post, but what is most striking about the engraving is the sky. We can see that Poussin’s sky – at least according to Gantrel – once had crackling thunder and heavy rain falling over the sea.

Moreover it appears to tell us that the lower part of Poussin’s clouds were dark and heavy, while the upper clouds were paler and lined with light. Very different indeed from the uniformly dark and heavy bank of clouds we now see hanging ominously over the top half of the painting.

It seems likely that Buttery did not have access to these copies of the Crossing of the Red Sea, or if he did, then he chose not to rely on them for his reconstruction of the damaged parts of the painting. Instead he chose to repair what remained of the image in the best way that he could, rather than attempt a reconstruction of what was lost. This circumspect approach is what most conservators feel is the most prudent thing to do where critical information is almost wholly lost from a painting. It is rarely considered advisable to reconstruct lost passages without having reliable information about what is missing.

This tapestry (seen here also digitally flipped from its original appearance) is less faithful to the original than Gantrel’s engraving, yet it too appears to show a more turbulent sky with the clouds defined by bright outlines.

The rediscovery of a “lost” replica

In the previous post we looked at Etienne Gantrel’s engraving and the Gobelins tapestry as tools for identifying some of the changes which have occurred to the NGV Poussin.

They certainly suggested that a considerable amount of change has occurred in the sky of our painting, however they are of limited use for a conservator attempting to recover or reconstruct lost passages of original paint. So though Horace Buttery may have been aware of them when he restored the painting in 1960, he may well have chosen not to rely on them for his treatment.

It is possible he may have known that a life-size painted replica had been made of Crossing of the Red Sea in the late seventeenth century. This was a copy said to be by none other than Charles Le Brun, the leading French artist at Versailles, and a painter who was directly inspired by Poussin. Unfortunately for Buttery, this replica had not been seen or recorded since 1773 and was considered lost or destroyed.

It therefore came as no small surprise when, in late 2009, Bernard Barryte, Curator of European Paintings at the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University in the United States contacted the NGV to let us know the lost replica had resurfaced. The copy, which is loan to the Cantor Center from a private collection, appears to have remained in a San Francisco Bay area collection for several decades, having been purchased in England sometime in the twentieth century.

Dr. Barryte sent us some photographs of the painting, which confirmed its high quality and faithfulness to Poussin’s original.

In May of 2011 I was able to go to California to examine the painting and arrange for high-resolution photography to be carried out.

Despite a discoloured varnish on its surface, the Stanford painting is in remarkably good condition, particularly in areas where our original is worn. Its value to our knowledge about the original is enormous. By virtue of the fact that the painting was executed with great skill and attention to detail, we are now able to use it as something like a documentary record of the painting at it appeared around 1685, some fifty years after the original was completed.

It has much to tell us about how the original has changed.

Attributed to Charles Le Brun, Crossing of the Red Sea (after Poussin) Oil painting on canvas, 158.1 x 213.4 cm

The Iris and B.Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University, USA

The NGV Crossing of the Red Sea by Nicolas Poussin Before conservation treatment.

At first glance there are two notable differences: the overall tonality of the original is much darker than the Stanford copy, and the clouds in the two paintings are now radically different. These features and other fascinating differences between the two will be examined in later posts.

The discovery of the replica has given us much to consider in light of the current restoration but also more generally in regards to Poussin and how we interpret his images.

The mystery figure in the NGV Crossing of the Red Sea

Detail of NGV Crossing of the Red Sea by Nicolas Poussin

Before the cleaning of Crossing of the Red Sea took place, there was one figure in it which had attracted attention from observant viewers. This figure in blue, nestled in among the throng of agitated Israelites, looked over her shoulder directly at the viewer. She drew attention because there was something odd about her in comparison with the figures nearby: the modeling of the paint in her face was much less refined than those of her companions, and she seemed contorted in a rather unusual way. There was a suspicion that the face was either severely worn or else the work of a restorer.

Detail from the Stanford University copy of Poussin’s Crossing of the Red Sea

When we referred to the Stanford replica, it showed a notably different figure. Though it had a similarly shaped body, the head was turned right around so that all that was visible was hair and a pair of ears. The engraving and the tapestry versions of the painting confirmed that Poussin painted the figure turned away from the viewer, so it appeared certain that the face we found on our Poussin must have been the work of a restorer. Therefore during the cleaning it came as a surprise to discover that the face was in fact original to the painting. Unlike the other areas of restoration, the paint of the face was not soluble in the cleaning solution, and when examined under high magnification it appeared consistent with the surrounding original paint with a similar craquelure, brush and pigment characteristics. But how could it possibly be by Poussin when the other copies and replicas told us the figure was turned the other way?

The answer appears to be that the face looking at the viewer was the first idea Poussin had, but after concluding that for some reason it did not work, he painted it out, replacing it with the head turned around the other way. If you look closely at the blue-clad body of the figure in the original, you can also see how the initial positioning of the body was different to its final appearance. The body was originally painted in a side-on pose, with just one shoulder visible. When Poussin decided to turn the figure’s head around he also turned the body around, adding the other shoulder which would have been obscured in profile in the first incarnation. The later-added shoulder and side of the body now appears different to the main part due to abrasion of the surface.

So how did we end up with the former head on the newer body? It is likely, during a previous cleaning, that a restorer identified the paint of the earlier face beneath the later one, and mistakenly took the later version for restoration. In cleaning off the top layer the restorer most probably believed that he was returning the image to Poussin’s original, which in fact he was, though surely unaware that the layer he was removing was Poussin’s intended version.

With the painting now cleaned, what remains to be done with the old head? There are three options:

- Leave the figure as it currently exists, that is, with the “old” head on the “new” body.

- Leave the “old” head, but paint out the added part of the body so that the older version of the figure appears in its original form.

- Re-paint Poussin’s modified head, covering over the original, thereby returning the figure to the final appearance left by the artist.

In the end, the decision is not a difficult one. In its present state the earlier head no longer sits comfortably with the body, appearing turned around in an impossibly contorted manner. Though it could be argued that the earlier head is more appealing than the final version, it is important to recognize that the artist had a problem with it and saw the need to change it. With the aid of the Stanford version of the painting it is now possible to return the head to the appearance Poussin intended, so this will almost certainly be the treatment path taken.

Fourteen months in seconds

Witness the transformation of Poussin’s Crossing of the Red Sea in this slideshow chronicling the various stages of conservation treatment: the removal of old varnish and restorations, the application of a new varnish, and the gradual process of inpainting the lost and worn passages of paint. If you look closely you will notice the changes first in the lower half of the painting, then up through the mountains and landscape, and finally throughout the sky.

Hover your mouse over the image to pause the slideshow.