The NGV was founded in 1861 and has been presenting performance works since the mid twentieth century. The processes through which these artworks enter the Gallery, and how they are documented and cared for while on site, are developing rapidly as understanding of what caring for them entails. This interview, conducted in July 2023 between Louise Lawson, Head of Conservation, Tate, London, and MaryJo Lelyveld, Manager, Conservation, NGV, explores why this might be the case and how conservation staff, or those entrusted with collection care in art museums, might better support and care for performance art–based works.

Louise Lawson (LL) Can you describe the place of performance and choreography artworks at the NGV?

Maryjo Lelyveld (ML) The NGV has a long history of staging performance. It offers a platform for local and international choreographers and performers to present their work to new audiences as well as engage with the NGV as a building and as a collection. Over the past few years, we are more actively commissioning, presenting and representing works in partnership with other organisations to understand how we can enable and support the ongoing lifecycles of performance art within the museum context. It is timely that we examine what documentation exists for these works and how they are captured across the various roles and memory repositories of the institution, given the historical variability of what falls under the terms ‘performance’ and ‘choreography’.

Choreographic or performance works developed for the art museum context that have been staged at the NGV include Gilbert and George’s The Singing Sculptures, 1973 (performed 1973); Jill Orr’s Marriage of the Bride to Art, 1994; Simone Forti’s Huddle, 1961 (reperformed 2018 while on loan to the NGV as part of MoMA at NGV: 130 Years of Modern and Contemporary Art); and Angela Goh’s Body Loss, 2017– (reperformed 2022). Similarly, there has been ongoing curatorial interest in this area of practice, with exhibitions routinely incorporating trans- and post-humanist works or performativity; for example, Stelarc’s The Extended Arm, 1999–2000, or Wade Marynowsky’s The Hosts: A Masquerade of Improvising Automatons, 2014.

Over the past few years, the offering of choreographic and performance works has grown substantially, with a strong focus not only on exhibitions but also connecting with local festivals. This includes Melbourne’s RISING festival, which featured local choreographer Lucy Guerin’s Pendulum, 2021, and Luke George and Daniel Kok’s Still Lives: Making a Mark, 2019 (reperformed 2022), as well as the NGV’s own exhibition-based performance program for Melbourne Now, which in 2023 included four new commissions by artists Alicia Frankovich and APHIDS, and choreographers Jo Lloyd and Joel Bray. As part of Precarious Movements: Choreography and the Museum the Gallery is commissioning and documenting two new works by international artists that will feature in the NGV Triennial 2023 program.

This is a very brief overview and doesn’t include various performances that fall under cultural or ceremonial performances, which take place at the NGV but draw upon deeper temporalities and specific cultural contexts. These works bring in different voices and considerations, but there are some very practical overlaps when it comes to working within our museum environment to support performance works.

LL What are you noticing when these works come into the museum? What’s emerging for you from a conservation perspective?

ML In our experience, the performance work is either commissioned or contracted by curators or Audience Engagement staff and coordinated as a public-facing program. This event-led process allows performances to be presented very efficiently. The museum’s Audience Engagement staff are familiar with the art museum’s audiences, work with a range of creative practitioners across media types and cultural practices, and routinely work with front-of-house, security, multimedia and marketing teams to stage performances and events. The focus is given to event delivery, logistics and compliance, and media requirements, with a temporal front-ending to produce and present the performance. Compared to object and other variable and time-based media that enters the museum, I feel there is less time given to understanding, supporting and documenting the artists’ intentions for the performance work, the conditions and impacts of the performance, evaluating the art–public interface or the artwork’s intended legacy and trace, and what forms its archiving should take. Material-based and digital-born artworks, whether collection or loan material, that are brought into the art museum are documented, recorded and vetted to ensure their care within the museum accords with industry ‘best practices’. These best practices consider the physical environment of the work, the artist’s intent for its presentation and ongoing maintenance needs for the display and life cycle of the work.

My own involvement with choreographic and performance works at the NGV began as part of a risk walk-through in the lead up to Angela Goh’s Body Loss, 2017–. The work was re-performed in 2022 in a public foyer space at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, which also had a collection furniture piece on display. Body Loss is very physical. The artist moves through the museum singing a single note, feeling her way through the space, which takes her into close proximity to other artworks and culminates in berries being eaten in the space. Conservation staff were invited to the risk walk-through to advise on how close the artist could perform in relation to the decorative art item on display and whether or not food was allowed in the space. These are standard practices when discussing public-facing and catered events in gallery spaces; however, given that Body Loss itself was an artwork, I found it interesting that NGV Conservation staff were not engaged in discussions about the care of the performance artwork. This example highlights the disjunct between standard workflows (Conservation advising on and being engaged with artwork care and its preservation) and the nature of the artwork, whether a physical object or the ecosystem that enables that artwork (for example, the performers, the building, the audience), being presented for that care.

Although the NGV has commissioned choreographic works, it is yet to acquire one, an activity that would trigger collection management workflows that involve other teams, such as Conservation and Registration. As such, there are limited collection management system (CMS) database records documenting performance and choreographic works that have been activated within our galleries. There is also limited supporting Conservation documentation that describes the scope and detailed parameters of the work, an evaluation of its condition (or the effectiveness of the work to communicate the artists’ intent, at a given time and place), along with supplementary documentation, such as artist questionnaires or artist’s notes for the work. Some documentation can be found in curatorial archives, but these tend to be focused more on correspondence leading up to the performance than the artwork itself. More recently, we have started recording these works through photographic and video documentation.

From a conservation perspective, having performance-based and choreographic works enter the Gallery is exciting because it prompts us to review our workflows and ambitions for preservation practice, not only for these works but also for the collection more generally. For example, how do we adapt our collection management system to meet the needs of choreographic works, and how does this impact the care practices for other works already in the collection and on loan? How does the institution undertake such an adaptation? Who is involved with the development of these new processes and what knowledges do they draw on? What methodologies and technologies are available to the institution for supporting the documentation, preservation or future activation of the work, given the distributed knowledges that constitute the work over time? Such knowledge carriers include not only those involved in the development, production and presentation of the work, but may also include the embodied or tacit knowledge of the dancers, the implicit knowledge of the choreographer in realising a work, the explicit knowledge required for production coordination, and the declarative knowledge that defines our collection management systems. The complexity of these works stretch these systems and connecting artists and art workers in new and exciting ways.

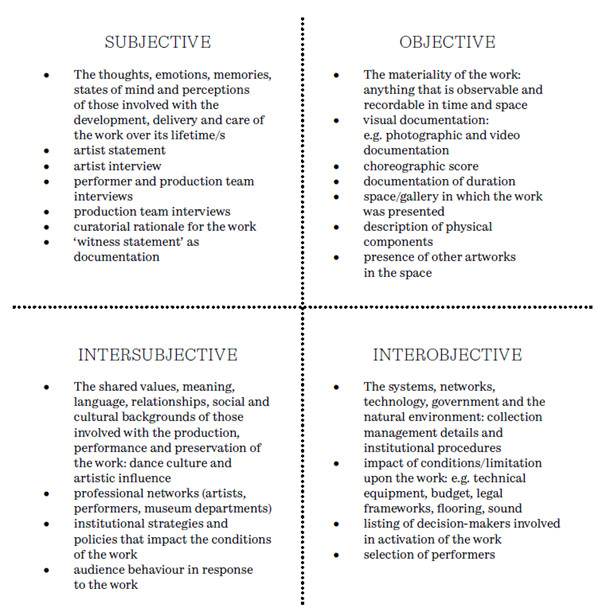

Conservators at contemporary art museums such as Tate have been grappling with the practical problem of ‘capturing’ performance art for well over a decade. Projects such as Documentation and Conservation of Performance at Tate (2016–21), Performance at Tate: Collecting, Archiving and Sharing Performance and the Performative (2014–16); Collecting the Performative (2012–13); and Performance and Performativity (2011) highlight the variability, instability and changeability of performance art and, most importantly, how its preservation is dependent on being attentive to the interobjective and intersubjective relationships such works entail.1 Louise Lawson, Acatia Finbow & Helia Marcal, ‘Developing a strategy for the conservation of performance-based artworks at Tate’, Journal of the Institute of Conservation, vol. 42. no. 2, pp. 114–34. This work has revealed the limitations of ‘objectivity’ within conservation by guiding us towards the documentation of interobjectivities – for example, the location and relationship of the dancers within the space and in relation to other artefacts and viewers, and the resulting effect on the performance. The Tate’s research projects have also mapped how conditions, procedures and policies have affected the work through shifting subjectivities and inter-subjectivities (see Table 1).

This alertness to documenting and preserving the work in its realisation across concurrent temporalities (for example, as a present performance and as future activations under different contexts) feeds the growing interest in conservation that seeks to synthesise rather than compartmentalise the various components and contexts of a work – to guide its preservation needs and expand preservation possibilities to incorporate ‘people, objects, place and time’2 Nicole Tse et al., ‘Preventive conservation: People, objects, place and time in the Philippines’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 274–81. and support the ‘becoming’ and ‘liminality’3 Helia Marcal, ‘Becoming difference: On the ethics of conserving the in-between’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 67, no. 1–2, pp. 30–37. of ‘active matter’.4 Peter N. Miller & Soon Kai Poh, Conserving Active Matter: Cultural Histories of the Material World, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2022. It suggests a dialogic approach that understands conservation as both a noun (profession) and verb (practice of care and protection that supports persistence). This has resulted in better support for preservation practices across all artwork and collection types.

Table 1: Aspects of a choreographic work that may be documented5This table draws from tools such as Tate’s ‘Performance specification’ and ‘Tate activation report and map of interactions’. See Louise Lawson, et al., ‘Strategy and glossary of terms for the documentation and conservation of performance’, Tate, <https://www. tate.org.uk/about-us/projects/documentation-conservation-performance/strategy-and-glossary>, accessed 17 Sep. 2023. to help map out the parameters of the work and its variability with each presentation, set within an Integral framework.6Ken Wilber, A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science, and Spirituality, Shambhala, Boulder, 2000.

LL Where are the tensions, where are the challenges in conserving performance works in the museum?

ML Internationally since the 1960s, public art museums generally, and conservation practice specifically, have been focused on professionalisation through the creation of definitions, specialist roles and the development of industry standards and museum ‘best practices’ in the acquisition, presentation, research and preservation of collections. Addressing some of the more restrictive or maladaptive aspects of this professionalisation, involving some unlearning by conservators and others within the institution, is required. There are many conservation guidelines, such as no food or drink in gallery spaces, that contradict what is needed for performance to thrive in the museum environment. Many of these guidelines, which may have started out as helpful standards for risk management, have become prescriptive rules that choreographic and performance works challenge. At best, these restrictions may be seen as an inconvenience for the artist, but at worst they diminish support for the artist and the choreographic work so that they receive less care than other artworks and artforms in the museum. Greater nuance and a dialogic approach are needed to deal with some of the perceived risks that presenting and preserving performance work presents.

The NGV is moving away from reliance on ‘expert care’ and leaning into more system-dependent preservation practices or networks of care where the conservator (or those entrusted with the longevity or trace of the works) acts as a facilitator between the choreographer and the institution.7Pip Laurenson & Vivian van Saaze, ‘Collecting performance-based art: New challenges and shifting perspectives’, in Outi Remes, Laura MacCulloch & Marika Leino (eds), Performativity in the Gallery: Staging Interactive Encounters, Peter Lang, Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2014, pp. 27–41; Annet Dekker, ‘Networks of care: Types, challenges and potentialities’, Networks of Care. Politiken des (Er)haltens und (Ent)sorgens, Berlin, 2022. The conservator is then engaged in understanding the parameters of the work and under what conditions it might be reactivated. This goes beyond good communication and documentation to involve developing an awareness and empathy for the different logics at play within those care networks, and honouring the collective responsibility for its preservation.

LL Where is your focus, and how would you like to progress in this area?

ML The NGV will be opening its third site, The Fox: NGV Contemporary (NGVC) in coming years. Planning for a dedicated contemporary art site and the works that will activate it is something we’re already thinking about, and I expect that choreographic art will be well represented. And although the building will feature the work of local and international artists, recent NGV exhibitions and involvement with festivals highlights the museum’s commitment to supporting the local creative landscape. I would like to continue presenting such work and facilitating its preservation. As we work through our own in-house documentation and workflows, I expect we’ll be drawing on the rich performance and choreographic art scene here in Victoria to establish our own networks of care, and developing our own conservation practice.

MaryJo Lelyveld is Manager, Conservation at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Louise Lawson is Head of Conservation at Tate.

Notes

Louise Lawson, Acatia Finbow & Helia Marcal, ‘Developing a strategy for the conservation of performance-based artworks at Tate’, Journal of the Institute of Conservation, vol. 42. no. 2, pp. 114–34.

Nicole Tse et al., ‘Preventive conservation: People, objects, place and time in the Philippines’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 274–81.

Helia Marcal, ‘Becoming difference: On the ethics of conserving the in-between’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 67, no. 1–2, pp. 30–37.

Peter N. Miller & Soon Kai Poh, Conserving Active Matter: Cultural Histories of the Material World, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2022.

This table draws from tools such as Tate’s ‘Performance specification’ and ‘Tate activation report and map of interactions’. See Louise Lawson, et al., ‘Strategy and glossary of terms for the documentation and conservation of performance’, Tate, <https://www. tate.org.uk/about-us/projects/documentation-conservation-performance/strategy-and-glossary>, accessed 17 Sep. 2023.

Ken Wilber, A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science, and Spirituality, Shambhala, Boulder, 2000.

Pip Laurenson & Vivian van Saaze, ‘Collecting performance-based art: New challenges and shifting perspectives’, in Outi Remes, Laura MacCulloch & Marika Leino (eds), Performativity in the Gallery: Staging Interactive Encounters, Peter Lang, Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2014, pp. 27–41; Annet Dekker, ‘Networks of care: Types, challenges and potentialities’, Networks of Care. Politiken des (Er)haltens und (Ent)sorgens, Berlin, 2022.