French Impressionism

Artwork Labels & Didactics

Artwork Labels & Didactics

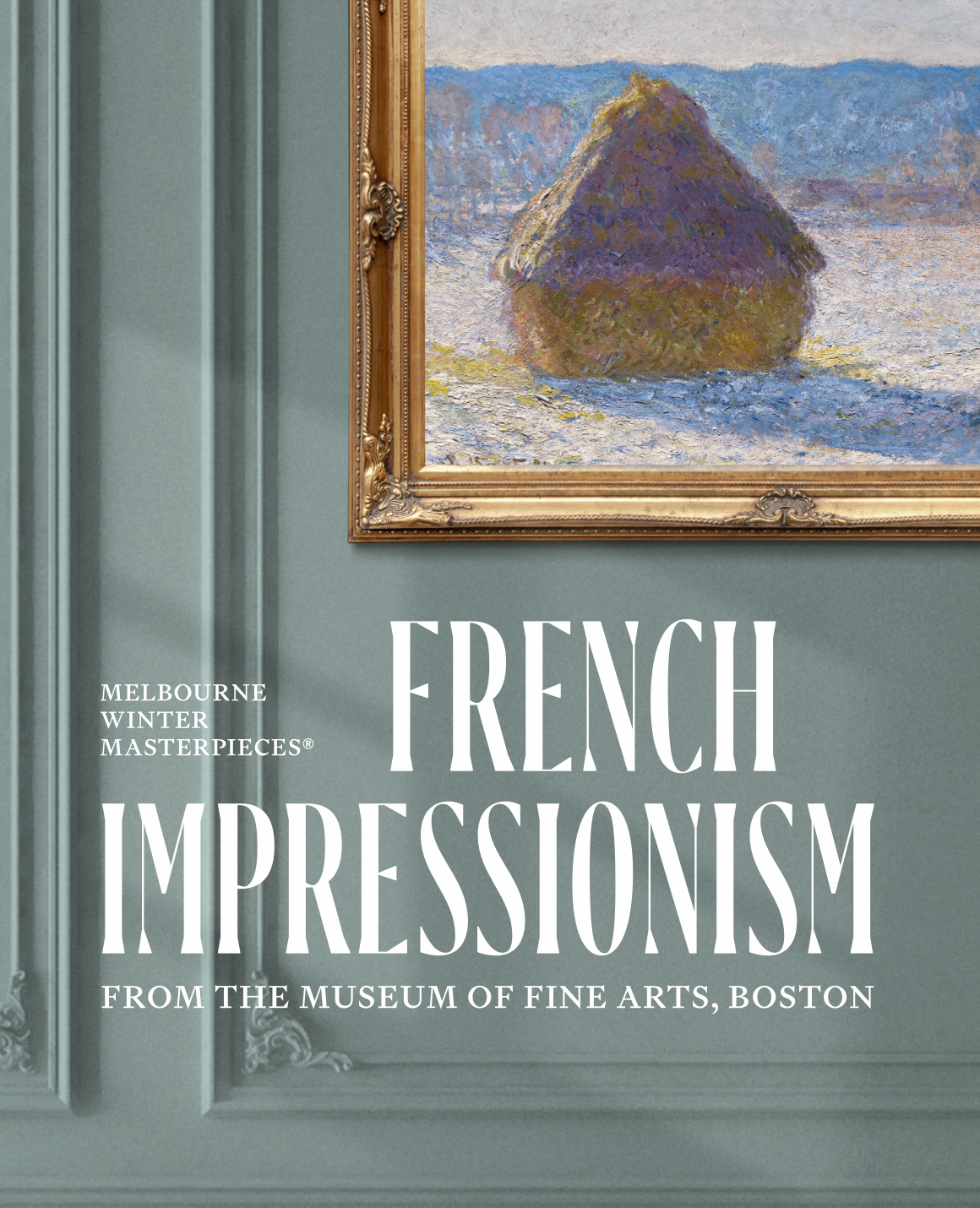

French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In 1874 a group of artists in Paris formed a society for the purpose of exhibiting their work independently of the Salon, the official exhibition program the French government established in 1748. This new group staged eight public exhibitions between 1874 and 1886, revealing an approach to painting that privileged ‘impressions’ – often painted en plein air (outdoors, directly in front of the subject) – over what the selecting judges for the Salon considered ‘finished’ works, which were highly academic in style and painted entirely in the studio. In critical responses to these independent exhibitions, this daring, varied and ambitious new painting became known as Impressionism.

The Impressionists were united by a common belief that they should respond to and represent the world around them. This was not a world populated by traditional art historical subjects, such as gods and goddesses, biblical figures or heroic military leaders. Instead, their attention was on the world in which they lived and worked, with a primary focus on nature.

Drawn from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, this exhibition presents more than one hundred artworks, including many that exemplify Impressionism at its high point in the mid 1870s, with such characteristics as luminous colour palettes, distinctive brushwork and scenes of the French countryside.

All works in this exhibition are from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, unless otherwise indicated.

Italy

Aphrodite

2nd century CE

marble

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1929 3071-D3

Francis Chantrey

English 1781–1841

George Canning

1828

marble

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1968 1540-D5

Impressionism in 1874

They are Impressionists in the sense that they render not the landscape, but the sensation produced by the landscape.

– Jules-Antoine Castagnary

Social connections among the artists played an important role in the development of Impressionism. These artists knew each other and each other’s work, and held strong opinions on the aims, limits and directions of their own art and the art world of their time. They wrote to and about one another, they sometimes painted side by side, and they exhibited together. Throughout the exhibition are extracts from letters, journal entries and other primary sources, which connect the artists’ voices to the fresh and inspiring vision for which Impressionism is so celebrated.

The role of artistic camaraderie is evoked by this pair of quintessentially Impressionist paintings by Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Monet and Renoir met as art students in Paris, and undertook numerous painting excursions together in the 1860s. Both artists loved to capture radiant outdoor light and vegetation, painting scenes suggestive of leisure and ease. Although their foci differed, both Renoir and Monet were committed to painting the world around them as they saw it, directly in front of the subject and en plein air (outdoors).

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

French 1841–1919

Woman with a parasol and small child on a sunlit hillside

c. 1874–76

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.593

Renoir’s model for this painting was likely Camille Monet, wife of his fellow Impressionist Claude Monet. Renoir painted her on several occasions between 1874 and 1876. Here she sits on a hillside, her white dress dappled with pink and blue in the shade. Her grace and composure stand in marked contrast to the child who wanders off into the background at right, oblivious to the painter’s presence. The feathery brushstrokes contrast with the thicker dabs and dashes used by Monet in the painting displayed adjacent. Renoir’s painting style was judged harshly by some fellow artists, such as Edgar Degas, who disdainfully remarked, ‘[H]e paints with balls of wool.’

Claude Monet

French 1840–1926

Meadow with poplars

c. 1875

oil on canvas

Bequest of David P. Kimball in memory of his wife Clara Bertram Kimball, 1923 23.505

Don’t you think that directly in nature and alone one does better?

– Monet

Throughout his life, Monet paid tribute to the central role played by nature – both the wild nature of the Normandy coast or the Forest of Fontainebleau, and the tamed nature of his gardens at Argenteuil or Giverny – in guiding his artistic vision. In this work from the mid 1870s, Monet uses contrasting highlights (red and green, purple and yellow) in bright impasto to bring the foreground closer to the viewer, while cool tones of more fluidly applied paint suggest the background’s recession to a hazy distance.

French Impressionism in Boston

Founded in 1630, Boston is one of the oldest cities in the United States. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) was established in 1870 and has been at the heart of cultural life in the city for over 155 years.

The founding mission of the MFA – one of the first fine art museums in the United States – was to collect, exhibit and preserve works of art for the enlightenment and enjoyment of the public. The institutions renowned collection of nearly 500,000 works has been created solely through private philanthropy, with no government funding for acquisitions.

Due to the foresight and dedication of collectors over many decades, the MFA’s French Impressionist holdings are among the most impressive of any museum in the world. This exhibition presents a selection of the museums most treasured works from this art movement, displayed in rooms that evoke the nineteenth-century residences of these generous Bostonians, as well as some of the spaces beloved by the artists themselves.

Before Impressionism

The Forest of Fontainebleau was a popular destination for artists during the 1820s–70s. Just over 50 kilometres south-east of Paris, it offered an abundance of natural motifs including rock formations and plains, as well as old-growth trees. The railway connection built in the middle of the century made the famed forest just over an hour’s journey from Paris, enabling easy access by tourists and artists.

The nearby villages of Chailly and Barbizon offered lodgings that attracted many artists, fostering a creative community who shared ideas or travelled together on painting excursions. After moving to Paris to pursue his artistic training, Claude Monet and his peers, who admired these artists and their direct engagement with the land, visited Barbizon and Chailly for extended painting sojourns in the early 1860s, their formative years as aspiring artists.

The name School of Barbizon was applied to artists who flocked to the small village of the same name in the 1830s and brought their paintings of rugged nature back to Paris, influencing the next generation of artists – the Impressionists.

Paul Huet

French 1803–69

The Forest of Compiègne

c. 1830

oil on canvas

Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, 2002 2002.124

Huet had first studied nature seriously as a teenager on the Île Seguin (an island in the Seine river) on the outskirts of Paris, before exploring the forest of Compiègne, north of Paris in 1826, at the age of twenty-three. His first forays in the forests of Fontainebleau took place somewhat late in his career, in 1850, and were thereafter transformative for his art. ‘I am amazed by this forest of Fontainebleau,’ he wrote in August 1850, ‘which is quite different from Compiègne in its savagery and variety.’ His regard for the vibrancy of nature is apparent in these five sketches, each capturing a view of the forest near the Château of Compiègne.

For kids

This painting is the oldest work in this exhibition, made around 1830. Instead of painting one scene on his canvas, Paul Huet has painted five. Huet has recorded landscapes from various viewpoints at different times during the day. These were studies for paintings he would later work on in his studio. All five scenes were painted in the same location: the forest of Compiègne, to the north of Paris, one of Huet’s favorite places to paint.

If you could set up an easel outdoors, where would you go and what would you paint?

Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña

French 1807–76

Clearing in the forest

c. 1855–70

oil on panel

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.537

In 1863 Diaz encountered a young man wearing the distinctive smock of a porcelain painter, struggling to compose a painting in the Forest of Fontainebleau. This was Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who received on-the-spot lessons in how to lighten his palette, which he never forgot, leading him to declare Diaz his grand homme (great hero). In this scene, the bright sky illuminates the trees and water beyond the shadowy foreground, elements that would have been instructive for Renoir. Diaz’s support of the younger artist continued through to the following decade, when he visited the very first Impressionist group exhibition, held in Paris in 1874.

Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña

French 1807–76

Pool in the forest

1858

oil on canvas

Bequest of Miss Elizabeth Howes, 1907 07.137

The composition of Diaz’s Pool in the forest bears a striking similarity to the Théodore Rousseau painting of the same title completed about eight years earlier, on display nearby. Diaz first met Rousseau in Parisian art circles around 1831, when Rousseau was only nineteen and Diaz twenty-three. After 1836 Diaz regularly encountered Rousseau at Barbizon and he quietly followed Rousseau into the woods of Fontainebleau, watching from afar as the younger landscapist painted outdoors. Gradually a friendship grew between the two men, and Rousseau shared the secret of his colour palette with Diaz, particularly the use of emerald green and Naples yellow.

Charles François Daubigny

French 1817–78

Road through the forest

c. 1865–70

oil on canvas

Gift of Mrs. Samuel Dennis Warren, 1890 90.200

It’s in the memory [of nature], or the sight of it, that we sometimes become crazy and it’s then that we make good paintings.

– Daubigny

Daubigny was criticised in his day for his often sketchy treatment of the landscape. The size of this painting and the artist’s signature confirm it as a finished work, not a preparatory sketch. In 1861 critic Théophile Gautier lamented: ‘It really is a pity that this landscapist, having so true and so natural a feeling for his subject, should content himself with an “impression” and neglect detail to a great extent. His pictures are mere sketches, barely begun.’ By the late 1860s Daubigny would become a champion for the younger generation including Cézanne, Monet, Pissarro and Renoir.

Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña

French 1807–76

Path through the forest near Fontainebleau

c. 1875–76

oil on panel

The Henry C. and Martha B. Angell Collection, 1919 19.105

I go to Barbizon to make Diaz paintings.

– Renoir

Diaz painted moody forest views throughout his career using dense and thickly applied paint. He favoured stormy and shadowy settings in which the light trunks of the forest’s beech and birch trees shone almost as if illuminated by lightning. Writing in 1873, the critic Jules Claretie mused: ‘Who better than Diaz knows how to steal one of the sun’s rays, in order to walk it cheerfully through the deep forests, on paths covered with moss, through the silver trunks of birches, on the lush foliage of oak trees?’ Diaz’s attention to the dappled play of light in the forest had a profound effect on Monet and Renoir.

Théodore Rousseau

French 1812–67

Pool in the forest

early 1850s

oil on canvas

Robert Dawson Evans Collection, 1917 17.3241

This forest view is typical of Rousseau’s style during this period: shadowy trees appear silhouetted against a sunlit field, as reflections of autumnal colours ripple on the watery surface below. Rousseau liked to immerse himself completely beneath the forest canopy, to study the uneasy truce between cultivated land and untamed nature at the forest’s edge, allowing the limits of his peripheral vision to naturally frame a chosen setting. One commentator recalled how he ‘had a cult for Fontainebleau’s old trees’.

Constant Troyon

French 1810–65

Sheep and shepherd in a landscape

c. 1854

oil on canvas

Bequest of Thomas Gold Appleton, 1884 84.276

Go to the country from time to time and make studies, and above all develop them. Do some copying at the Louvre. Come and see me often: show me what you’re doing and with enough courage you’ll make it.

– Monet’s account of advice received from Troyon, 1859

Troyon was both a landscapist and an animalier (animal painter). This landscape combines the artist’s interests by featuring a rural worker riding a donkey and herding a flock of sheep in a luminous country setting. Troyon experimented with light effects, with the cloudy sky casting a dramatic shadow in the mid-ground of the landscape. A wide variety of brushstrokes and an array of greens enlivens the lush setting. The young Monet was so impressed by Troyon’s work when he first encountered it at the Paris Salon of 1859 that he approached the older artist for advice. Ultimately, however, Monet did not follow Troyon’s recommendation that he take life-drawing classes and focus on figure studies.

Claude Monet

French 1840–1926

Woodgatherers at the edge of the forest

c. 1863

oil on panel

Henry H. and Zoe Oliver Sherman Fund, 1974 1974.325

Théodore Rousseau made some very beautiful landscapes… Daubigny, now there is a fellow who does well, who understands nature! The Corots are unadorned marvels.

– Monet

This early work reflects Monet’s admiration for the landscape painters of the previous generation, centred around the village of Barbizon on the edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau. Their commitment to direct observation and ability to find beauty in commonplace scenes set the precedent for Impressionism. Monet painted this in 1863, when he travelled to Fontainebleau in search of new motifs. His choice of subject matter and a darker colour palette echo the rural labourers and tranquil forest views of Millet and Rousseau. The baton of plein-air painting was therefore handed to a new generation of painters, nurtured in the sylvan glades of Fontainebleau.

For kids

As a young artist, Claude Monet made several trips to the countryside to paint outdoors. In this painting Monet has included two people carrying bundles of wood on their backs. The figure closest to us seems to walk slowly under the weight of their load. The wood was likely gathered to sell as kindling and firewood. Monet has hinted at the time of day – late afternoon – by recording how the long shadows and areas of sunshine affect the appearance of the field and trees.

What season do you think this was painted in? How is this like other paintings in this room?

Théodore Rousseau

French 1812–67

Edge of the woods (Plain of Barbizon near Fontainebleau)

c. 1850–60

oil on canvas

Bequest of Mrs. David P. Kimball, 1923 23.399

I will never get old, as long as I have my eyes to see.

– Rousseau

Direct observation from nature in the forests and clearings of Fontainebleau lay at the heart of Rousseau’s work. He first settled near the Forest of Fontainebleau for a sustained painting campaign in the winter of 1836–37. Entranced by the region, he also spent the next three autumns and winters in Barbizon, enjoying these seasons when most other artists and tourists had left, and he could be alone in the nearby forest. His preference for autumnal subjects contributed to his renown as a colourist, as did his mastery of an immense palette of greens, russets and browns.

Jean-François Millet

French 1814–75

Shepherdess leaning on her staff

c. 1852–53

oil on canvas

Robert Dawson Evans Collection, 1917 17.3245

While Millet at times painted idyllic rural landscape scenes, he was primarily interested in documenting the daily lives of the poor workers in Barbizon and Fontainebleau. The image of a solitary shepherdess tending her flock became a favourite motif in Millet’s depictions of French peasants and labourers. Seemingly lost in thought, the cloaked figure of the shepherdess stands quietly beside an embankment, separated from the grazing sheep. Small-scale canvases like this were attractive to private collectors; this work was sold by Millet to prominent American artist William Morris Hunt, who painted alongside Millet in Barbizon in the early 1850s.

Jean-François Millet

French 1814–75

End of the hamlet of Gruchy

1856

oil on canvas

Gift of Quincy Adams Shaw through Quincy Adams Shaw, Jr., and Mrs. Marian Shaw Haughton, 1917 17.1501

My goal was to show the habitual peacefulness of the place, where each act, which would be nothing anywhere else, here becomes an event.

– Millet

Although Millet left his birthplace in Normandy as a young man to pursue his artistic training in Paris, he retained deep emotional connections to his hometown of Gruchy and to this vista in particular. He painted several versions of this composition over a number of years. Describing the impact of this view, Millet reflected: ‘Going down toward the sea, suddenly one faces the great marine view and the boundless horizon. Near the last house, an old elm stands against the infinite void. How long has this poor old tree stood there beaten by the north wind?’

Jean-François Millet

French 1814–75

Millet’s family home at Gruchy

1854

oil on canvas

Gift of the Reverend and Mrs. Frederick A. Frothingham, 1893 93.1461

Millet initially intended to be a portrait painter. However, in 1846 he met the landscape artists Constant Troyon and Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña, with Diaz later helping Millet to sell works through the Parisian dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. The following year Millet befriended Théodore Rousseau, which further cemented his commitment to painting the French countryside and the rural labours of its peasant occupants. Acting on the advice of Diaz, Millet settled in Barbizon with his wife and children in the summer of 1849. Millet started this painting when the artist returned to his childhood home in Gruchy on the Normandy coast in 1854 after his mother’s death.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

French 1796–1875

Souvenir of a meadow at Brunoy

c. 1855–65

oil on canvas

Gift of Augustus Hemenway in memory of Louis and Amy Hemenway Cabot, 1916 16.1

Brunoy is situated halfway between Paris and Fontainebleau. Corot’s painting, as the title suggests, is nostalgic. In the 1850s and 1860s Corot began to use the word souvenir (memory) in the titles of his paintings, indicating that they were not to be read as direct transcriptions of observed nature. The artist’s light touch, the feathery quivering leaves and the silvery tones of the sky reinforce the atmospheric, evocative quality of the landscape. Flowers created with dabs of pigment, figures gathering plants or ambling down a wooded path, and a cow gazing docilely towards the viewer add visual variety to this peaceful pastoral scene.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

French 1796–1875

Twilight

1845–60

oil on canvas

Bequest of Mrs. Henry Lee Higginson, in memory of her husband, 1935 35.1163

Although Corot began painting outdoors in Fontainebleau as early as 1822, drawing directly from nature was only part of his creative process. Corot also specialised in paysages composés (constructed landscapes) that combined naturalistic details with imaginative flourishes, recalling the lyrically artificial landscapes painted by Claude Lorrain in the seventeenth century. Twilight is a classic example, with its delicate balance of light and shadow capturing the precise atmospheric effect of twilight as two young women gather fruit in a clearing. Darkly silhouetted trees frame the last glimmer of sunlight caught on the surface of a lake or pond.

Eugène Boudin: Exemplar to the Impressionists

To bathe in the depths of the sky. To express the gentleness of clouds … to set the blue of the sky alight. I can feel all this within me, poised and awaiting expression. What joy and yet what torment!

– Eugène Boudin

Both Eugène Boudin and Claude Monet grew up in Normandy and maintained a lifelong friendship after meeting early in their respective careers. Boudin encouraged Monet, who was sixteen years his junior, to paint outdoors, telling him ‘a work painted directly on the spot has always a strength, a power, a vividness of touch that one doesn’t find again in the studio’. Boudin’s paintings feature a unifying focus on water and sky – a fascination shared with Monet and the younger Impressionists.

Monet would credit Boudin with his artistic formation, recalling how: ‘One day Boudin said to me: “Learn to draw well and appreciate the sea, the light, the blue sky.” I took his advice and together we went on long outings during which I painted constantly from nature. This was how I came to understand nature and learned to love it passionately … I have said it before and can only repeat that I owe everything to Boudin and I attribute my success to him.’

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Fashionable figures on the beach

1865

oil on panel

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John J. Wilson, 1974 1974.565

I shall do other things but I shall always be the painter of beaches.

– Boudin

The advent of train travel in the 1850s brought seaside holidays within reach for middle-class Parisians, who flocked to new resort towns on the Normandy coast. Boudin painted scenes of fashionable urban beachgoers in 1862 and found a steady market for luminous, light-hearted pictures like this one. His acute power of observation conveys details of up-to-the-minute trends in women’s fashion and also captures subtle, yet distinct, qualities of light and weather. Committed to painting outdoors rather than in a traditional studio, Boudin encouraged his young friend and pupil Claude Monet to work outside – from nature, in nature.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Venice, Santa Maria della Salute from San Giorgio

1895

oil on canvas

Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, 1925 25.111

At the age of sixty-eight, Boudin travelled to Venice for the first time, returning there in the summer of 1894 and again in 1895, painting at least two other versions of this scene. He made only slight variations from one painting to the other in the placement of boats and human figures. The real difference between the works and what interested him most were the cloud formations in the sky, the light and the atmosphere, which captured different effects of light and season on the same subject.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Washerwomen near a bridge

1883

oil on panel

Bequest of David P. Kimball in memory of his wife Clara Bertram Kimball, 1923 23.512

As in most paintings by Boudin, great attention is given here to the texture and colour of the cloud-filled sky and the rippling surface of the water, as well as the interplay between the two. Less characteristic is the focus on women labouring at the water’s edge, the bright white of clean laundry gleaming atop the heaps in the baskets behind them. People loiter and horse-drawn carriages move across the bridge, their sketchier rendering contributing to the sense of movement.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Figures on the beach

1893

oil on canvas

Bequest of William A. Coolidge, 1993 1993.32

Three brushstrokes directly from nature are worth more than two days of work in the studio.

– Boudin

A storm is looming: diagonal strokes at the horizon line indicate wind and rain. Yet bathers wade at low tide on the Normandy beach, seemingly untroubled by the approaching weather. Their parasols and hitched skirts are conjured with a few deft dots of paint. Boudin’s treatment of fleeting light and weather effects and the bold spontaneity of his pictures exemplify the influential role he held for Impressionist painters, most notably Monet. In 1869 the critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary wrote perceptively about Boudin’s work: ‘This is the ocean and you can almost smell the salty fragrance.’

For kids

Eugène Boudin liked to observe and paint the sky. One of his friends, the artist Camille Corot, called him the ‘king of the skies’. Boudin lived by the sea, and travelled up and down the coast capturing the sky’s changing colours and textures. In this painting, a mass of grey clouds threaten rain – in fact, it looks like it is raining heavily in the distance. Water on the sand reflects the dark sky. Small dashes of paint indicate groups of people about to get caught in the storm.

Take a look around this room. Many of these paintings record similar scenes, but there are differences between them. Can you spot any?

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Deauville at low tide

1897

oil on canvas

Bequest of Mary H. J. Parker, 1981 1981.719

Here we are in Paris. Time to pack our bags and then back to Deauville … yes, indeed! I must admit I am looking forward to seeing our beaches again and our overcast skies.

– Boudin

In this late work, tiny strokes of paint skilfully denote figures along the inner shoreline and at the water’s edge, as blue sky peeks through a span of textured clouds. Boudin emphasises the expansive stretch of dunes and beachfront that recedes into the distance. Tiny sailboats dot the sliver of ocean at right, beneath a sweep of billowing clouds tinged with delicate purple shading.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

The inlet at Berck (Pas-de-Calais)

1882

oil on canvas

Bequest of Mrs. Stephen S. FitzGerald, 1964 64.1905

Many of Boudin’s paintings depict the fashionable Parisian tourists who flocked to Normandy starting in the 1850s. By the latter part of the 1860s, however, he had grown disenchanted with the crowds of chic Parisians, writing: ‘one feels almost ashamed at painting the idle rich’. In this view of Berck, a fishing and resort town, he instead explored the strand itself, bordered by simple houses, scattered with fence posts and tufts of seagrass. Boudin, who was aptly called the ‘king of the skies’ by fellow artist Camille Corot, fills nearly three-quarters of this composition with a delicately nuanced view of grey clouds.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Juan-les-Pins, the bay and the shore

1893

oil on canvas

Gift of Eunice and Julian Cohen, 1999 1999.584

Boudin turned his attention to Venice and the French Riviera in the 1890s.The Mediterranean coast was then, as now, a popular resort during winter. Monet had visited the small town of Juan-les-Pins in 1888, staying in nearby Antibes from January to May. Fellow Impressionist artist Mary Cassatt brought her ailing mother to Antibes in 1894 and could see Juan-les-Pins from the window of their rental. Boudin includes figures seated on an embankment, with parasols near the trees, as well as small boats resting at the coastline, all suggestive of the rest and leisure to be enjoyed in the area.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Ships at Le Havre

1887

oil on panel

Gift of Miss Amelia Peabody, 1937 37.1212

As an adolescent, Boudin had a year of schooling in Le Havre before working in a printer’s shop and then a stationer’s store that also exhibited works by visiting painters. In this way, he came to know the Barbizon School artists Jean-François Millet and Constant Troyon, whose work influenced him. But it was not so much the town and its shops than the harbour and its ships that interested Boudin. Here the delicate strokes portraying the ships’ masts and rigging vibrate against the brushy clouds. Tiny figures occupy rowboats and the wharf, diminutive in comparison to the towering ships and sky.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Trouville, jetties at low tide

1885

oil on panel

Bequest of Forsyth Wickes – The Forsyth Wickes Collection, 1965

65.2638

This quiet view of the harbour at Trouville in Normandy belies the bustling crowds of the popular beachside town. Depicted at low tide, sailboats moored in the harbour have become stranded, while a fisherman in a tiny rowboat takes advantage of the calm waters. Even in this small painting, Boudin draws attention to the vastness of the sky, the vertical masts drawing the viewer’s attention skyward. A narrow passageway between the jetties hints at the open ocean just beyond, as distant sailboats list in the wind.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Harbour scene

c. 1888–95

oil on panel

Gift of Mrs. Henry Bliss, 1967 67.906

Boudin painted ships in port under virtually all-weather conditions. In this variation of one of his favourite views of sailing vessels along a wharf, he creates a more sombre view with subtle shades of grey. Boudin painted hundreds of pictures like this one, with myriad effects of watery reflections and sunlight through the clouds – each a unique expression of a particular place and moment in time.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Port of Le Havre

c. 1886

oil on canvas

Bequest of Miss Elizabeth Howard Bartol, 1927 RES.27.90

According to the poet Charles Baudelaire (1821–67), Boudin’s remarkable skills of observation made it possible to ‘divine there the season, the hour, the wind. I don’t exaggerate!’ His exactitude in depicting particular conditions of light, weather and atmosphere is readily apparent in this view of the bustling harbour of Le Havre, a prominent port city on the English Channel where both Boudin and Monet grew up. A three-masted ship dominates the foreground, its French flag flying proudly in the breeze, as small rowboats bring passengers to and from the large ships anchored in deeper water.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Port scene

c. 1880

oil on panel

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.521

When Boudin and Monet were introduced in the late 1850s, Monet was still a teenager, sketching caricatures of local personalities in Le Havre. Boudin soon convinced the younger artist to attempt painting outdoors and, following Boudin’s example, Monet abandoned his caricatures and devoted himself to painting. Boudin’s marine paintings were intimate in scale and were popular souvenirs among the middle-class Parisian tourists who became a driving force in the art market in the late nineteenth century. Despite its scale, this painting captures the sweep and expanse of the seaside and sky, while its subtle palette evokes the closeness of moist sea air on a cloudy day.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Harbour entrance

1873

oil on canvas

The Henry C. and Martha B. Angell Collection, 1919 19.98

By the 1870s Boudin’s marine paintings shifted away from crowded beaches to focus on views of harbours, ports and coastlines. In this unassuming harbour scene, Boudin reveals a quiet energy beneath the subtle shimmer of the water’s surface, as the sun’s warm light breaks through the clouds. Quick brushstrokes animate the placid reflections of the boats, while the nearly monochrome palette mirrors grey skies in the silvery water below. By 1873, when this work was completed, Boudin had found a clientele who appreciated the subtlety of his velvety grey images of overcast harbours.

Eugène Louis Boudin

French 1824–98

Harbour at Honfleur

1865

oil on paper mounted on panel

Anonymous gift, 1971 1971.425

There’s a large number of us herein Honfleur at this point … [Johan]Jongkind and Boudin are here, we get along famously and don’t leave each other’s side.

– Monet, 1864

Throughout his life, Boudin repeatedly spent summers in the town of Honfleur, where he was born – it was an ideal setting for his seascapes and harbour views. Typically, these works depict the Honfleur harbour and coast, rather than the open ocean. Boudin, like the younger Monet, admired and learnt from the Dutch marine painter Johan Jongkind (whose works are also included in this exhibition), who had moved permanently to France in 1860 after living there between 1846 and 1855. With his consistent focus on the sky and its varied effects, Boudin also liked to employ unexpected compositions. Here the quay juts into the foreground, its triangular shape drawing our eye towards the horizon.

In the studio

While they spent much time painting outdoors, the Impressionists also worked in the studio for many reasons, such as creating still-life paintings. ‘I’m astonished that these painted studies of flowers find any takers, it is such a painterly feeling I’m always astounded that anyone but painters has a taste for them,’ confided Henri Fantin-Latour about his still-life paintings. For some of the Impressionist painters, however, their still-life paintings found a ready market, possibly because their compositions were more conventionally appealing than their landscapes.

In practical terms, still-life subjects were easier to arrange and light – a creative alternative to the vagaries of weather when working outdoors. Still life also allowed the artists to work towards their painterly goals, as Berthe Morisot observed: ‘To catch the fleeting moment – anything, however small, a smile, a flower, a fruit – is an ambition.’ Others, like Paul Cézanne, were more specific and enthusiastic: ‘As to flowers, I have given them up. They wilt immediately. Fruits are more reliable. They love having their portraits done.’

Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña

French 1807–76

Flowers

c. 1850–60

oil on canvas

Bequest of Ellen F. Moseley

24.236

Diaz was a member of the Barbizon School, the group of French landscape painters who were important precursors to the Impressionists. This flower piece, one of only a few by Diaz, is painted with his characteristic vigorous brushwork and interest in generalising individual forms into broad areas of colour. The bright pastel colours allude to Diaz’s early training as a porcelain decorator.

Gustave Courbet

French 1819–77

Hollyhocks in a copper bowl

1872

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.530

I am coining money out of flowers.

– Courbet

Despite the profitability of still lifes, Courbet painted very few of them in his career, and those he did paint were often created out of necessity. In September 1871 he was sentenced to six months in the prison at Sainte-Pélagie for his involvement in the destruction of the Vendôme Column during the popular uprising known as the Paris Commune earlier that year. During this period, Courbet was denied both live models and access to the prison roof to paint landscapes, so his subjects became the fruit, fish and flowers delivered by his sister. The context of isolation within which he was working explains several of this painting’s compositional elements, including the dark, sombre background engulfing the hollyhocks.

Alfred Sisley

British (active in France) 1839–99

Grapes and walnuts on a table

1876

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.601

Sisley painted only nine still lifes, remaining committed to landscape painting throughout his career. This work is believed to have been painted with the encouragement of his friend Monet. Like the still lifes of Sisley’s fellow Impressionists, this painting captures both the objects on display – a selection of fruit on a plate, walnuts, a knife and a nutcracker – and the changing atmospheric conditions. The casual arrangement of the items across a crisp white tablecloth resembles forms found in a natural landscape, a subject that Sisley and many of his fellow Impressionists more readily embraced.

Édouard Manet

French 1832–83

Basket of fruit

c. 1864

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.576

The still life is the touchstone of the painter.

– Manet

While Manet observed the conventions of traditional still-life painters, he paid equal attention to transcribing the world around him, claiming that ‘one has to belong to his own time and reproduce what he sees’. Using innovative and experimental pictorial techniques, Manet countered the symbolic and decorative traditions long associated with still-life painting. Painted early in Manet’s career, this still life is characterised by loose, abbreviated brushstrokes. Despite the ridicule Manet received for the flatness, brevity and abstract quality of his painting style, he deemed this work sufficiently finished to include in his first solo exhibition in 1867.

Henri Fantin-Latour

French 1836–1904

Plate of peaches

1862

oil on canvas

M. Theresa B. Hopkins Fund, 1960 60.792

Fantin-Latour often selected commonplace, domestic subjects, as is demonstrated in this early, informal composition of three peaches, a plate and a fruit knife. This unusually small composition betrays Fantin-Latour’s debt to Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin, the eighteenth-century master of the still life, who regained popularity among artists and connoisseurs in the early 1860s. Although Fantin-Latour’s approach to still-life painting remained relatively conservative, the nuanced transitions from shades of yellow to red to brown in Plate of peaches underscore the artist’s great attention to colour and subtleties of light effects, a fascination he shared with his Impressionist contemporaries.

Henri Fantin-Latour

French 1836–1904

Roses in a glass vase

1890

oil on canvas

Bequest of Alice A. Hay, 1987 1987.291

I’m astonished that these painted studies of flowers find any takers, it is such a painterly feeling I’m always astounded that anyone but painters has a taste for them.

– Fantin-Latour

During an extended visit to London in 1861, Fantin-Latour was introduced to the collectors and art enthusiasts Mr and Mrs Edwin Edwards, who subsequently brokered many sales of his paintings in England. The artist’s many compositions of roses in glass vases were particularly successful with private collectors in England, where the cultivation of roses had surpassed that of France. Minutely observed still lifes of flowers, like this one, are among Fantin-Latour’s most celebrated works. These share the Impressionists’ interest in direct observation and domestic intimacy, but they also possess a hushed, timeless quality far removed from the immediacy of Impressionist landscapes.

Henri Fantin-Latour

French 1836–1904

Roses in a vase

1872

oil on canvas

Frederick Brown Fund, 1940 40.232

Unlike his friend Manet, Fantin-Latour remained committed to the more conservative realist tradition, capturing a level of naturalistic detail – particularly in his compositions of roses in glass vases – that Manet never sought to record. In these relatively austere still lifes, Fantin-Latour concentrated on the specific forms of the individual flowers, adopting a short, feathery brushstroke to render the petals. Fantin-Latour was the late nineteenth-century’s undisputed master of the rose. Here a rough, scumbled background offsets the delicacy and fleshy softness of these overblown blossoms, so real we can almost smell their perfume.

Henri Fantin-Latour

French 1836–1904

Flowers and fruit on a table

1865

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.540

Fantin-Latour met Manet and Degas at the Louvre Museum, where they went in the late 1850s and early 1860s to copy Old Master paintings. Fantin-Latour quickly fell in with the pair’s avant-garde circle but refused to participate in the Impressionists’ group exhibitions of the 1870s, choosing instead to continue showing his work at the official Salon. He produced still lifes often with very casual compositions like this one, and once claimed to ‘put a great deal of thought into the arrangement of random objects’ to give ‘the appearance of a total lack of artistry’.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

French 1841–1919

Mixed flowers in an earthenware pot

c. 1869

oil on paperboard mounted on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.592

Some Impressionist artists strived to bring highly naturalistic and ‘living’ effects to their still lifes, representing the textures, colours and vibrancy found in nature using idiosyncratic brushwork and bright palettes. This is reflected in this painting by Renoir, which captures both the subject – an arrangement of dahlias, asters and sunflowers in a stoneware pot alongside a selection of apples and pears – and its surrounding atmosphere. The painting marks Renoir’s closest collaboration with Monet; the young artists painted the same subject, sitting side by side before the arrangement. Monet’s version of the composition is now in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

For kids

When he was thirteen, Pierre-Auguste Renoir left school to start work in a porcelain factory. He was trained to paint porcelain objects like vases and plates with delicate bouquets of flowers and other pretty scenes. This vase of brightly coloured flowers shows that Renoir continued to use the skills he learned as a porcelain painter when he was painting on canvas.

Can you recognise any of the flowers in Renoir’s arrangement?

Paul Cézanne

French 1839–1906

Fruit and a jug on a table

c. 1890–94

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.524

I want to astonish Paris with an apple.

– Cézanne

Described by critic Thadée Natanson as the ‘master of still life’, Cézanne, like Manet, dedicated roughly a fifth of his oeuvre to the genre. While his practice was informed by the Impressionists’ aims, his vision was fundamentally distinct from theirs. Rather than seeking to capture ephemeral impressions, Cézanne’s chief objective was to investigate form, structure and colour, and the relationships between these compositional elements. Still life was the central subject matter through which he conducted his research. His dedication to still-life painting produced complex, carefully sculpted compositions laden with inanimate objects.

Gustave Caillebotte

French 1848–94

Fruit displayed on a stand

c. 1881–82

oil on canvas

Fanny P. Mason Fund in memory of Alice Thevin, 1979

1979.196

Caillebotte found his subject for this modern still life in the display of an upmarket fruit seller, likely near the independently wealthy artist’s Paris home. In traditional still-life paintings, fruits are arranged on tables near dishes or cutlery, suggesting a domestic setting. Here white wrappers and the distribution of fruits by kind makes evident that these are commodities for sale. Caillebotte’s unconventional choice of subject matter was praised in 1882 by writer and critic Joris-Karl Huysmans, who described the artist’s depiction of fruits of varying shape, size and colour on their ‘white paper beds’ as ‘extraordinary’ and heralded the painting as a ‘still life freed from its routine’.

For kids

This painting is different from the other images of fruit in this room. Instead of a bowl filled with a few pieces of fruit displayed on a table, the artist has painted a fruit stall. He has painted it just as the grocer arranged it, very carefully, with each ripe fruit sitting in a cradle of white paper. Some of the fruits, like the figs, oranges and berries, would have been grown in warm climates.

What colours has the artist used to paint the different fruits?

Berthe Morisot

French 1841–95

White flowers in a bowl

1885

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.581

Morisot was introduced to the Impressionist circle in 1869 by Manet, her mentor, close friend and eventual brother-in-law. She quickly became a core member of the group and participated in all but one of the eight Impressionist exhibitions. As an upper middle–class woman, Morisot was unhindered by financial hardship. Unlike Monet and Renoir, her livelihood did not depend on the sale of her paintings. As a result, she was able to produce highly experimental works. This still life exemplifies Morisot’s immediate and direct approach to painting, with its sweeping brushstrokes that capture the subject with a minimum of loose, fluid lines and forms.

Watery surfaces

Flickering colour and light on rippling watery surfaces were favoured subjects for the Impressionists and their friends. Direct engagement with the fleeting and momentary nature of water is paired with innovative compositions in which the viewer appears to hover above or float on the surface of a body of water. Édouard Manet dubbed Claude Monet the ‘Raphael of water’, his achievements in capturing its many moods and appearances overshadowing those around him.

Charles François Daubigny, an older artist who was a great champion of Monet’s work, first created a studio boat, or floating atelier, for painting rivers on location. Like Eugène Boudin, Johan Barthold Jongkind, a Dutch marine painter who spent much of his career in France, also encouraged the young Monet’s interest in marine painting. Monet’s peers took a variety of approaches to waterways: some, like the Norwegian Frits Thaulow, revelled in rippling colours and reflections. Others, like Paul Cézanne, used expanses of pond water to challenge the perception of depth and space in their compositions. Alfred Sisley also experimented with compositions and effects, describing the river Loing, a regular subject in his work, as ‘so beautiful, so translucent, so changeable’.

Frits Thaulow

Norwegian 1847–1906

River view

c. 1890–1900

oil on canvas

Deposited by the Trustees of the White Fund, Lawrence, Massachusetts Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

L-R 3.1989

Time and again, Thaulow painted waterways as though from a boat or precariously close-range on land, revelling in the moving surface of the water. He created immersive compositions such as this one, in which no other intruding vessels or visitors interrupt the luminous, shimmering tableau. Glistening ripples extend across the river to the edge of the canvas in this late autumn scene. The last orange-red leaves drift upon the river’s surface. Above, glimmers of sky, clouds and trees swirl together. A contemporary critic applauded how ‘the mass, the fluidity and the depth’ within such works surpasses the mere flickering sensations of Impressionist painting.

For kids

Frits Thaulow painted River view from an unusual point of view. When you first look at the painting, it seems as if you could wade right into the glistening, swirling water. The river ripples right out to the edges of the canvas, as if Thaulow painted while he was standing waist-deep in the water! This was not the case. Thaulow remained dry but wanted to create a detailed painting of the river that captured its changing surface.

Spend time looking at the surface of the water the artist has painted. Can you spot leaves floating downriver? What else do you notice about the water?

Frits Thaulow

Norwegian 1847–1906

Abbeville

c. 1894

oil on canvas

Deposited by the Trustees of the White Fund, Lawrence, Massachusetts

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

L-R 1329.12

I will remain … the naturalist that I always was: I will always attempt to produce the illusion that I observed in nature.

– Thaulow

Although he did not participate in their group exhibitions, Thaulow knew many of the Impressionists, including Monet, having spent much of his career in France. Thaulow visited Paris in 1882–83, exhibited at the 1889 Exposition Universelle and moved to France definitively in 1892. He visited Abbeville, a commune in northern France on the Somme river, in 1894. Thaulow conveys the subtle swirling of the river’s surface with astonishing variety. Luminous blues and greens represent the sky’s reflection on the moving water, while touches of additional colours, reflected from the architecture, glow near the river’s edges. The overcast day provided a captivating quality of light, lending mysteriousness to the simple, familiar waterway.

Charles François Daubigny

French 1817–78

Woman washing clothes at the edge of a river

c. 1860–70

oil on canvas

Gift of Louisa W. and Marian R. Case, 1920 20.1864

We are only bothered by the steamboats, and there are a lot of them going back and forth.

– Daubigny

By the late 1860s, the Barbizon School painter Charles Daubigny would become a champion for the younger generation including Cézanne, Monet, Pissarro and Renoir. Monet wrote to Boudin enthusiastically about Daubigny: ‘Here is one who does well, who understands nature!’ In this painting, Daubigny captures the way that colours seem abnormally bright on a clear day, which places the viewer in the middle of the river itself – the placid water spreads nearly from edge to edge. Daubigny realised this immersive composition through his inventive use of a boat repurposed as a floating studio, an idea later taken up by Monet in the 1870s.

Alfred Sisley

British (active in France) 1839–99

Waterworks at Marly

c. 1876

oil on canvas

Gift of Miss Olive Simes, 1945

45.662

The artist’s impression is the life-giving factor … the surface, at times raised to the highest pitch of liveliness, should transmit to the beholder the sensation which possessed the artist.

– Sisley

Although less celebrated than some of his colleagues such as Monet, Sisley maintained an emphatically Impressionist sensibility throughout his career. Waterworks at Marly exemplifies Sisley’s enduring efforts to translate his ‘sensation’ to canvas. From the rippling water to the rustling foliage of burnt orange and ochre, Sisley ignites the senses in a view of what may otherwise be a rather unremarkable subject – a pumping station that provided water for the fountains at the Palace of Versailles.

Alfred Sisley

British (active in France) 1839–99

La Croix-Blanche at Saint-Mammès

1884

oil on canvas

Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, 1939 39.680

This painting, titled for the grand seventeenth-century manor La Croix-Blanche shown at the right, illustrates Sisley’s masterful blending of light and colour throughout all elements of the landscape. ‘The sky must be the medium,’ he wrote, ‘the sky cannot be a mere backdrop.’ Here the bright sky graduates from delicate blue at the upper left to a nearly white glow at centre – while the water’s distant, pale tones deepen to navy as the river approaches. Although Sisley’s vision may begin with the sky, the water’s surface also subtly connects land, water and sky in the finished work.

Alfred Sisley

British (active in France) 1839–99

The Loing at Saint-Mammès

1882

oil on canvas

Bequest of William A. Coolidge, 1993 1993.44

Every picture shows a spot with which the artist has fallen in love.

– Sisley

Between 1880 and 1885, Sisley painted nearly three hundred scenes of the riverside town of Saint-Mammès, located 60 kilometres outside Paris. This quiet bend of the Loing river is lined with poplar trees, boats, houses and an arching railway viaduct that spans the distant horizon line. Sisley was particularly attached to this river, a tributary of the Seine that meets it at Saint-Mammès.‘The waters of the Loing, so beautiful, so translucent, so changeable,’ he wrote. Of note here is what Sisley called the ‘variation of surface within the same picture’, which he felt was crucial to ‘rendering a light effect’.

Paul Cézanne

French 1839–1906

The pond

c. 1877–79

oil on canvas

Tompkins Collection–Arthur Gordon Tompkins Fund, 1948 48.244

From far off one often gets an entirely different idea of things. But likewise when one is too close one sees nothing; you can’t see a Cézanne by holding it against your nose.

– Pissarro

Cézanne exhibited in two of the eight Impressionist exhibitions, including the first one, held in Paris from 15 April to 15 May 1874. He worked closely alongside his elder colleague Pissarro in the 1870s and emulated his technique of using regular, directional brushwork. The rhythmic, even brushstrokes of The pond, particularly visible in the hillside and the tree at right, create a feeling of solidity rather than depth or movement.

Claude Monet

French 1840–1926

Grand Canal, Venice

1908

oil on canvas

Bequest of Alexander Cochrane, 1919 19.171

When I looked at your Venice paintings with their admirable interpretation of the motifs I know so well, I experienced a deep emotion … I admire them as the highest manifestation of your art.

– Signac

Venice, Monet once told his wife, was ‘too beautiful to paint’. But when he accepted the invitation of an American friend to stay at her rented palazzo on the Grand Canal in 1908, he set to work, painting thirty-seven canvases over the course of his visit. This view, taken from the boat landing of the Palazzo Barbaro, captures the baroque church of Santa Maria della Salute and its reflection dancing on the water. Unlike many painters of Venetian views, Monet showed less interest in representing famous monuments than in capturing the play of light and reflection on the city’s waterways.

For kids

In autumn of 1908, Claude Monet spent two months in the Italian city of Venice. During his visit, he often set up his easel beside the city’s famous canals. This painting shows a famous church called Santa Maria della Salute, which sits at one end of Venice’s Grand Canal. On the left are the poles used to tie up boats and gondolas. Monet’s main interest seems to have been recording changes in the atmosphere around the church, from the shifting clouds to the glimmering surface of the water.

Monet liked to paint the same subjects multiple times to capture how the colours and light would change over time. At what time of day do you think Monet painted this canvas?

Johan Barthold Jongkind

Dutch 1819–91

Harbour scene in Holland

1868

oil on canvas

Gift of Count Cecil Pecci-Blunt, 1961

61.1242

[Jongkind] asked to see my sketches, invited me to come and work with him, explained to me the why and the wherefore of his manner, and thereby completed the teachings that I had already received from Boudin.

– Monet

Although he was of Dutch origin, Jongkind studied and painted in France from the mid 1840s onwards, later meeting Monet and Boudin, among other artists, during repeated stays in Normandy in the 1860s. While Jongkind moved permanently to France in 1860, he periodically returned to the Netherlands for visits throughout the decade, with this painting made on one of his final visits. It underscores Jongkind’s lively touch – the complex arrangement of light and shadow sparkling upon the water’s surface, with small dabs of paint creating a palpable sense of movement and energy throughout the bustling harbour.

Johan Barthold Jongkind

Dutch 1819–91

Harbour by moonlight

1871

oil on canvas

The Henry C. and Martha B. Angell Collection, 1919 19.95

[There is] always something to gain from studying Jongkind’s landscapes because he paints what he sees and what he feels with sincerity.

– Monet

In the 1870s Boudin and Monet both visited the Netherlands, not only to study the accomplishments of seventeenth-century Dutch painters, but undoubtedly also to appreciate firsthand the watery landscape familiar to them from Jongkind’s works. Although Jongkind did not return to his Dutch homeland after 1869, elements reminiscent of it continued to appear in his works. Here a windmill identifies this painting’s Dutch setting. The main subject, though, is the scintillating moonlight playing off the clouds and across the surface of the water.

Camille Pissarro: Mentor and mentee

Perhaps we all come from Pissarro.

– Paul Cézanne

Camille Pissarro was the oldest member of the Impressionist group and among its most daring innovators. He was a dedicated family man, living outside of Paris where costs were more manageable, but despite living away from the artistic centre, Pissarro remained abreast of new directions and was sought out by others for advice. He was also open to learning from others. In the latter half of the 1880s, Pissarro experimented with Neo-Impressionism, having been introduced to its younger practitioners by his son Lucien.

Neo-Impressionism abandoned the wet-on-wet application of harmonious tones preferred by Impressionism in favour of placing strong, opposing blocks of colour side by side. Pissarro’s interest in this new painting technique, however, was short-lived. His own distinctive vision demanded a less rigorously theoretical approach. By 1895 Pissarro was exasperated with critics who derided superficial similarities between his works and the work of others: ‘In Cézanne’s show at Vollard’s there are certain landscapes of Auvers and Pontoise that [they say] are similar to mine. Naturally, we were always together! But what cannot be denied is that each of us kept the only thing that counts, the unique “sensation”!’

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

French 1796–1875

Turn in the road

c. 1868–70

oil on canvas

Gift of Robert Jordan from the collection of Eben D. Jordan, 1924 24.214

Pissarro always acknowledged the great debt his work owed to the Barbizon School painter Corot. In the late 1850s Pissarro had been a regular visitor to Corot’s studio, and he declared himself a ‘pupil of Corot’ when first submitting works to the Paris Salon exhibitions. Here the tall spindly trees, dappled foliage and silvery, cool palette are typical of Corot’s late work, which often stemmed more from the artist’s imagination, imbued as it was with years of landscape study. The figures populating this quiet woodland scene are all stock characters Corot reused in many different compositions.

Paul Gauguin

French 1848–1903

Entrance to the village of Osny

1882–83

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.545

[Pissarro] looked at everybody, you say! Why not? Everyone looked at him, too.

– Gauguin

A young stockbroker, Gauguin was an ex–merchant marine and French naval officer who, with little formal instruction, began to paint in 1873. He first exhibited with the Impressionists in 1879, and in the same year he visited Pissarro in Pontoise for the first time, painting alongside him outdoors. While Gauguin was still working as a stockbroker in 1882, he frequently travelled to Pontoise on Sundays to visit with Pissarro and paint his own views of the town. This composition, a complex depiction of a hamlet some fifty minutes’ walk from Pontoise, was probably painted during one of these weekend visits.

Camille Pissarro

French (born in the Danish West Indies) 1830–1903

Sunlight on the road, Pontoise

1874

oil on canvas

Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, 1925 25.114

Do not forget, one merely has to be oneself! But what an effort this requires!

– Pissarro

Pissarro was an important mentor to many of the mostly younger artists with whom he associated, and to whom he offered advice on painting and lessons on life. In this scene of a village road beside a river in Pontoise, Pissarro used the cool, blonde palette and buttery style of paint application typical of his early work. He has saturated the composition with spots of lush colour, which are used to great effect to capture shimmering water and dappled sunlight playing over earth and grass alike. Both Cézanne and Gauguin worked alongside Pissarro as they developed their artistic careers, adopting characteristic features of his work into their own. Gauguin also collected Pissarro’s work and lent to exhibitions during the artist’s lifetime.

Paul Cézanne

French 1839–1906

Turn in the road

c. 1881

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.525

Pissarro was a father to me. He was a wise counsellor and something like God Almighty.

– Cézanne

Both Pissarro and Cézanne were fascinated by debate over the importance of representational accuracy in landscape painting versus alterations for the sake of compositional interest. Cézanne was a young art student when he first met Pissarro in 1861. From late 1872 until mid 1874 Cézanne lived in Auvers-sur-Oise, just under ninety minutes’ walk from Pontoise, in order to work more closely with his elder friend and mentor. Cézanne lived in Pontoise itself from May to October 1881, and returned there again the following summer, painting outdoors alongside Pissarro. This work was painted during this time of direct dialogue between the two artists.

Vincent van Gogh

Dutch (worked in France) 1853–90

Houses at Auvers

1890

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.549

In Antwerp I did not even know what the Impressionists were, now I have seen them and though not being one of the club, yet I have much admired certain Impressionist pictures.

– Van Gogh, 1886

When Van Gogh arrived in Paris in February 1886, his aesthetic was still guided principally by seventeenth-century Dutch Old Masters and French landscape painters of the Barbizon School. His brother, Theo, an art dealer in Paris, had been urging him for some time to introduce more light and colour into his work. Once in France, Van Gogh achieved this. In May 1890 Van Gogh moved to Auvers, north-west of the capital, at the recommendation of Pissarro. Auvers was favoured by artists he admired and was also home to Dr Paul Gachet, described by Pissarro to Theo as ‘a man who has been in touch with all the Impressionists’.

For kids

The winding road is an interesting device in paintings. Its changing, diagonal lines create a fascinating composition (the various parts of a picture that the artist brings together). Your eye travels along the road and into the scene. It helps create a sense of depth. It also makes us wonder what, or who, we might find if we could travel further along the path.

Imagine walking along the path in this painting and the ones nearby. Where do you think they might lead?

Paul Signac

French 1863–1935

View of the Seine at Herblay

1889

oil on canvas

Gift of Mrs. Charles Sumner Bird (Julia Appleton Bird), 1980 1980.367

Signac’s variety of brushstrokes – dots, dabs and dashes – helps to suggest different textures and also gives the composition here a visual energy, an optical quiver. The pale grey of the primed canvas is evident between strokes, especially in the water and sky, creating a silvery mid tone and a sense of the work being rapidly made. Drawn lines at the water’s edge and the crest of the hill, as well as the thoughtful use of colours opposite each other on the colour wheel (like orange and blue in the reflection of the foliage), reveal the artist’s careful planning.

Paul Signac

French 1863–1935

Port of Saint-Cast

1890

oil on canvas

Gift of William A. Coolidge, 1991 1991.584

In front of a divided picture, it will be advisable first to stand far enough away to perceive the impression of the whole, then stop and come closer to study the play of coloured elements.

– Signac

Signac was a keen sailor who owned more than thirty different boats during his lifetime. He was drawn to the French coast, where he applied the Neo-Impressionist technique to capture startling stretches of iridescent water. Port of Saint-Cast is one of a series of four seascapes that Signac painted along the coast of Brittany. The idea of working in series may have come from Monet. Signac’s composition is spare and carefully balanced, with the painstaking method of applying dabs of paint enlivened by vibrant colour and light. The subtlety of his attention to colour and touch evokes the granular texture of the sand and the shimmering surface of the water as it ripples towards the shore.

Camille Pissarro

French (born in the Danish West Indies) 1830–1903

Pontoise, the road to Gisors in winter

1873

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.587

Pontoise, a sizeable rural town roughly 30 kilometres north-west of Paris, was Pissarro’s primary base for close to twenty years. From the 1860s through to the early 1880s he painted some three hundred views of the town’s centre and his favourite corners of its less densely populated outskirts. France experienced unusually harsh winters and heavy snowfall in the early 1870s. This street scene shows residents sweeping up a light dusting of snow beneath a sky that promises more, the town’s rural architecture and the lowering sky evoked with short, broad strokes of juxtaposed, unblended colour.

Camille Pissarro

French (born in the Danish West Indies) 1830–1903

Two peasant women in a meadow (Le Pré)

1893

oil on canvas

Deposited by the Trustees of the White Fund, Lawrence, Massachusetts Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston L-R

1333.12

How can one combine the purity and simplicity of the dot with the fullness, suppleness, liberty, spontaneity and freshness of sensation postulated by Impressionist art?

– Pissarro

In this seemingly simple depiction of peasant women conversing and cows grazing, Pissarro worked through complex technical concerns. His use of a variety of brushstrokes enlivens the composition and suggests the differing textures of grass, fabric and foliage, as well as the movement of a breeze. Suffering from an eye ailment, Pissarro worked less directly before nature in this period, applying Seurat’s new scientific theories of colour and optics to paintings completed principally in his studio.

Camille Pissarro

French (born in the Danish West Indies) 1830–1903

Spring pasture

1889

oil on canvas

Deposited by the Trustees of the White Fund, Lawrence, Massachusetts Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston L-R

1323.12

The great problem that has to be solved, is the matter of relating everything in the picture, even the smallest details, to the overall harmony.

– Pissarro

Pissarro’s art moved into an entirely new phase in October 1885, when he met the young painters Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who were exploring scientific theories of colour and optics, in works that became known as Neo-Impressionism (also known as Pointillism, after the French word for ‘dot’, point). Painted with countless tiny, palpitating strokes, this painting reflects Pissarro’s experimentation with Neo-Impressionism. Placing dabs of colour side by side, according to Pissarro, ‘stirs up more intense luminosities than does mixture of pigments’. Here the vibrant greensand cool blues employed by Pissarro evoke the freshness of spring.

For kids

In the mid 1880s, Camille Pissarro became interested in a new style of painting called Pointillism. This painting technique involves using the tip of a paintbrush to create small, distinct dots of colour on the surface of the canvas. When finished, the coloured dots mix in your eye to form a complete image, like this scene of a woman and goat in a lush green field.

Take a closer look at this painting by Pissarro, and at the paintings by Paul Signac nearby. Up close, you can see how each artist has applied dots of pure pigment to the surface of their canvases. Then take a step back and see it all come together!

Camille Pissarro

French (born in the Danish West Indies) 1830–1903

Morning sunlight on the snow, Éragny-sur-Epte

1895

oil on canvas

The John Pickering Lyman Collection – Gift of Miss Theodora Lyman, 1919 19.1321

In April 1884 Pissarro moved to Éragny-sur-Epte, where he would mostly reside until his death in 1903.In this painting, a peasant woman trudges through the snow, her back to the viewer, her arms taut with the weight of two buckets. Pissarro combines here his sympathy for rural labourers with his interest in winter landscapes. Committed across several decades to humble rural scenes and flickering brushstrokes, Pissarro varied his touch from the broader Impressionist stroke to a more methodical Neo-Impressionist dot and back again. From the late 1880s, Pissarro suffered from an eye condition that made it difficult to work out-of-doors for long periods. He probably painted this scene from the window of his studio, a converted barn in Éragny.

Paul Signac

French 1863–1935

Gasometers at Clichy

1886

oil on canvas

National Gallery of Victoria Felton Bequest, 1948 1817-4

This painting is one of the first works painted by Signac according to Neo-Impressionist principles. From the beginning of his practice, Signac’s landscapes imaged semi-industrial locales. This choice followed naturally from his family’s move in 1880 to Asnières, an outer area of Paris that was dotted with factories, cranes, chimney stacks and large gas-storage tanks. The contradiction inherent in this painting, a luminous depiction of an unimposing urban scene, is part of the work’s radical intent. The subversive nature of such aesthetically pleasing urban landscapes lies in their depiction of the polluted locales of working-class Paris – districts that were seldom visited by the wealthy Parisian socialites or members of the bourgeoisie who constituted the artist’s viewing public.

Urban realisms

The new painters have tried to render the walk, the movement, and hustle and bustle of passers-by, just as they have tried to render the trembling of leaves, the shimmer of water, and the vibration of sun-drenched air.

– Edmond Duranty

While much Impressionist art celebrates natural light and outdoor suburban or coastal scenes, certain artists thrived on the energy and rapid change of urban life and, in turn, on the regular interaction with other artists that the city afforded. They were enthralled by Paris’s lively entertainments, motivated by the accessibility of professional models, and absorbed by the everyday experiences of the city streets and the way people lived. As Edgar Degas wrote of his home and the source of his subjects, ‘Paris is charming and is not work the only possession one can always have at will?’

Increasing urbanisation and industrialisation brought rapid change to social customs and fashions. In Paris, such spectacle both attracted and repelled, creating interest as well as anxiety. The Impressionists and their circle reflected these changes in their scenes of urban subjects. Édouard Manet’s childhood friend Antonin Proust recalled that Manet revelled in the modernisation of Paris under Napoleon III, and saw art and artistry in the renewed city precincts, its grand boulevards and great stone edifices: ‘[W]ith Manet, the eye played such a big role that Paris has never known a flâneur [one who walks the streets, observing the crowd] like him nor a flâneur strolling more usefully.’

Jean-François Raffaëlli

French 1850–1924

Garlic seller

c. 1880

oil on paper mounted and extended on canvas

The Henry C. and Martha B. Angell Collection 19.103

Raffaëlli began his career as a history painter but was soon converted to the ‘new school’ of painting championed by Degas and Manet. He was invited by Degas to participate in the fifth and sixth Impressionist exhibitions of 1880 and 1881. Exhibited in 1881, Garlic seller depicts an itinerant street vendor. Many of Raffaëlli’s paintings offer detailed visual descriptions of life in the rapidly growing suburbs encircling Paris. Raffaëlli himself moved to the suburb of Asnières in 1879, where he could closely observe his fellow citizens. Eschewing the picturesque for suburban actuality, Raffaëlli was acclaimed by critic Jules Claretie as ‘the painter of the disenfranchised, the poet of the Parisian suburbs’ and hailed for achieving a new form of realism.

Edgar Degas

French 1834–1917

Portrait of a man

c. 1865–70

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.532

Although his father, a successful banker, encouraged him to focus his artistic energies on the potentially lucrative genre of portraiture, Degas never made a career for himself as a portraitist. He restricted his work in this vein to close friends and family members, of which the unidentified sitter for this picture is almost certainly one. The young man’s elegant attire and searching, melancholy gaze mark him as a member of the artist’s rarefied social circle.

Edgar Degas

French 1834–1917

After the bath III

1891–92

lithograph

Schorr Collection Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

L-R 21.1994

Often in Degas’s artistic practice, it is art that generates art, rather than direct observation of a phenomenon. This lithograph relates closely to Nude woman standing, also displayed here, the familiar figure and setting now in reverse. The printmaking process afforded Degas the opportunity to repeat, rework and revise figures and entire compositions, resulting in extended groups of similar scenes. This was particularly pertinent for depictions of repetitive activities, like bathing or rehearsing a dance, that are themselves experienced in life as iterative, recurring often with only subtle variation from time to time.

Edgar Degas

French 1834–1917

Nude woman standing, drying herself

1891–92

lithograph, transfer from monotype, crayon, tusche, and scraping

Katherine E. Bullard Fund in memory of Francis Bullard, by exchange, 1983 1983.313

Degas exhibited pastels (some over monotype) of women bathing at the1877 and 1886 Impressionist exhibitions. Mary Cassatt and Gustave Caillebotte both owned such works made by their friend. Some critics observed that Degas’s bathers were viewed as though through a keyhole and this later lithograph likewise presents a private moment as if surreptitiously viewed. As the woman leans to the side, drying herself, her hair falls dramatically. Its inky mass is repeated in two hairpieces on the tufted chaise next to her. The domestic setting confirms that this is a modern woman attending to her ablutions rather than a nymph or goddess.

Edgar Degas

French 1834–1917

Ballet dancer with arms crossed

c. 1872

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.534

What’s underneath is no-one’s business. Works of art must be left with some mystery about them.

– Degas

Degas completed a great number of sketches at the opera and theatre – the urban playgrounds that inspired his most acclaimed works. This painting demonstrates his method of sketching contours and then building mass and form with colour and tone. Found in Degas’s studio after his death in 1917, this work is evidently unfinished, yet captures the artist’s most distinctive painterly traits. Partial focus, selective intensity of vision, unconventional perspective and figures caught unposed or in movement – these are some of the aspects that tether Degas’s images to a specific instant in time, giving them their sense of realism.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

French 1864–1901

Carmen Gaudin in the artist’s studio

1888

oil on canvas

Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 1948 48.605

Although Lautrec was only a child when the first Impressionist exhibitions were held, by 1882 he was an art student in Paris. This portrait of Carmen Gaudin, a professional artist’s model with distinctive red hair, is unlike the caricatural depictions of cabaret and circus performers that dominate Lautrec’s works from around 1890. Rather, it belongs more to the ‘Impressionist realism’ of Degas and Manet. The life of a professional model was difficult and fraught with social stigma, her employment dependent on whether her look fitted an artist’s vision. When Gaudin changed her locks from red to brown, Lautrec no longer hired her.

Victorine Meurent

French 1844–1927

Self-portrait

c. 1876

oil on canvas

Arthur Gordon Tompkins Fund 2021.554

Meurent made her debut as a painter at the Paris Salon in 1876 – although she is most remembered for being an artist’s model. Manet’s favourite for over a decade, Meurent most sensationally modelled for his 1863 works Olympia and Luncheon on the grass (both Musée d’Orsay, Paris). In this room, she is the subject of a bust-length portrait by Manet, as well as his near life-size Street singer. Here, however, we see Meurent as she saw herself. Her face turns towards us, and her expression suggests serious concentration. Found in a Paris flea market in 2010 and acquired by the MFA Boston in 2021 (the first museum outside France to acquire Meurent’s work), this could be the very painting that she entered into the Salon in 1876.

Édouard Manet

French 1832–83

Victorine Meurent

c. 1862

oil on canvas

Gift of Richard C. Paine in memory of his father, Robert Treat Paine 2nd, 1946 46.846

While Manet never participated in the so-called ‘Impressionist exhibitions’ held between 1874 and 1886, he was a friend and mentor to Degas, Monet and other Impressionist artists. Victorine Meurent was Manet’s great model and muse in the 1860s. Her oval face, russet hair and grey eyes appear in many of the artist’s most ambitious paintings of the period, including Street singer, on view nearby. This smaller portrait was probably Manet’s first painting of Meurent, made when she was still a teenager. It conveys a sense of wary intimacy far removed from his subsequent large-scale works.

Édouard Manet

French 1832–83

Street singer

c. 1862

oil on canvas

Bequest of Sarah Choate Sears in memory of her husband, Joshua Montgomery Sears, 1966 66.304

A picture like this, over and above the subject matter, is enhanced by its very austerity; one feels the keen search for truth.

– Émile Zola, writer