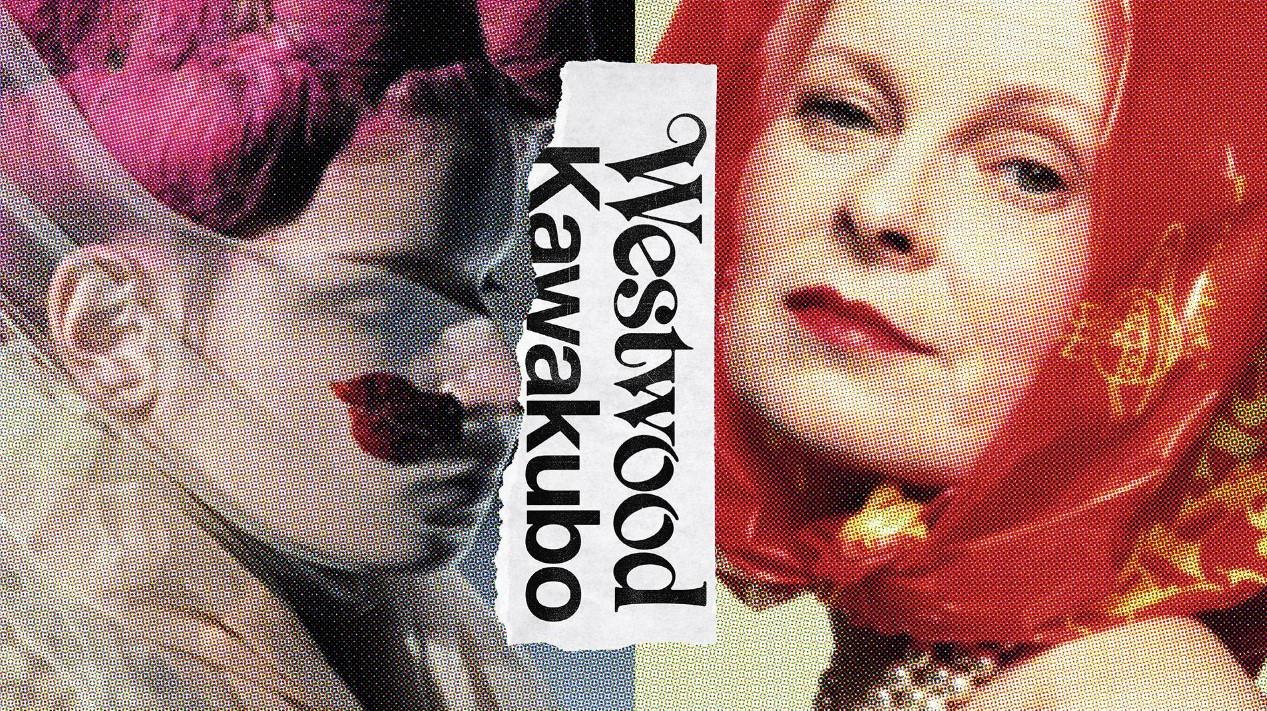

The following is an abridged version of the timeline that appears in the Westwood | Kawakubo exhibition.

1940s–60s

Westwood

Vivienne Westwood is born Vivienne Isabel Swire on 8 April 1941 in the English mill town of Glossop, Derbyshire.

The day after Westwood is born, nearby Birmingham is bombed by the Nazi Luftwaffe (German Air Force) as part of the Blitz, an eight-month campaign of aerial attacks on British towns and cities that results in over 43,000 civilian deaths.

Vivienne Westwood aged 15, c. 1956.

In 1958 Westwood and her family move to the town of Harrow, Greater London, where she undertakes a jewellery and silversmithing course at Harrow Art School.

In late 1961, while studying teaching in London, Westwood meets and later marries her first husband, Derek Westwood, wearing a wedding dress of her own creation:

‘I made my wedding dress myself. Not very well – and it wasn’t even finished. It was still all pinned together and it wasn’t finished properly. I made it to the church on time. Ish. Just.’

In 1965 Westwood divorces her husband and meets Malcolm McLaren, who later becomes the manager of several prominent punk and New Wave bands, including the Sex Pistols. She begins a new career in fashion.

The 1960s in London are marked by the emergence of countercultural movements which see the city become a centre for alternative music and fashion. These movements are characterised by a rejection of traditional values and societal norms, and a focus on self-expression.

Two dominant, opposing youth subcultures emerge amid this change: the clean-cut, scooter-riding, blues-obsessed ‘mods’, and the leather-jacket-wearing, motorcycle-riding ‘rockers’. The latter are now recognised as precursors to the punk subculture that would take shape the following decade.

Kawakubo

Rei Kawakubo is born in Tokyo on 11 October 1942.

In March 1945 the United States Air Force conducts the largest aerial bombing raid in history on Tokyo, resulting in the deaths of over 100,000 civilians.

In August 1945, the US drops two atomic bombs, first on Hiroshima and then on Nagasaki. Japan surrenders to the Allies in September, ending the Second World War, but is placed under US occupation until 1952.

Kawakubo is raised by her mother in Tokyo, within a period of significant urban transformation and cultural change:

‘Up until fifteen or so, my mother made my clothes. And I also wore school uniforms … I did express myself by doing things with my socks … I pushed them down … Radical.’

Tokyo, c. 1964.

In the 1960s, Japan emerges as a global economic power. Amid this period of rapid industrialisation and technological advancement, Japanese fashion undergoes a significant shift from tailor-made clothing to affordable ready-to-wear styles, mirroring similar developments in Western fashion.

These broader shifts also usher in an era of social and political upheaval, which sees the emergence of avant-garde artist groups and filmmakers centred in Tokyo. Subcultural fashions – such as the preppy American Ivy League–inspired Miyuki-zoku style – become bolder, driven by youth culture and a vibrant publishing scene.

In 1964 Kawakubo graduates from Keio University with a degree in fine art and aesthetics. She leaves home, moving into an apartment in Tokyo’s fashionable Harajuku district. After working in advertising then as a freelance stylist, she begins making clothes, motivated by not being able to find what she wants to wear. In 1969 the label Comme des Garçons (French for ‘like some boys’) is born.

1970s

Westwood

Let It Rock shopfront, photographed for an an magazine, 1972.

Throughout 1971, countercultural protests take place across London. On 6 March, the newly formed women’s liberation movement marches for equal pay and equal rights. In October, informal Gay Pride marches are staged to advocate for sexual freedom.

In 1971, amid these broader social developments, Westwood and McLaren open Let It Rock, a small boutique at 430 King’s Road. They sell vintage and new clothes, records and memorabilia. The shop is rebranded four times: as Too Fast To Live, Too Young To Die (1972–74), then SEX (1974–76), then Seditionaries (1976–79), and finally as Worlds End (1979–83). Each iteration of the shop introduces a bold new fit-out. Westwood and McLaren’s DIY ethos and provocative designs, worn by the likes of the Sex Pistols, are credited with shaping the early look of punk.

Kawakubo

The first Comme des Garçons flagship store, Minami-Aoyama district, Tokyo, 1976.

In the early 1970s, Japan witnesses the rise of environmental activism and the women’s liberation movement, and the end of the country’s postwar economic boom.

In 1973 Kawakubo incorporates Comme des Garçons, Co. Ltd and opens the first flagship store in Tokyo in 1976. Unlike typical retail environments, there are no window displays or mirrors in the boutique. The garments are loose-fitting, inspired by workwear and folk traditions.

Also during this decade, Kawakubo, accompanied by fellow Japanese fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto, visits Westwood and McLaren’s King’s Road store. McLaren remembers the designers as ‘excellent customers’.

1980s

Westwood

Westwood and McLaren’s 1981 Pirate collection, photographed by Australian-born London-based photographer Robyn Beeche.

In 1980s London, amid the political conservatism of the Thatcher administration and ‘Princess Diana fever’, subcultural style is harnessed as a source of resistance to and liberation from the status quo. The early 1980s are dominated by the decline of punk and the emergence of the New Romantics, distinguished by theatrical, flamboyant and androgynous fashions. A legacy of punk, the goth aesthetic also develops during this period.

Westwood’s collections begin to interrogate Savile Row tailoring techniques and ideas of ‘Britishness’. She captures the creative energy of the decade, merging disparate contemporary and historical references. Her source material ranges from nineteenth-century patterns to screenprinted stills taken from the 1982 science-fiction film Blade Runner.

In 1981 Westwood and McLaren present a collection titled Pirate, and Kawakubo presents her autumn–winter 1981–82 collection, later titled Pirates. Though radically different in their inception and presentation, both collections represent a subversion of the fashion codes of the time and mark a definitive shift in each designer’s practice.

Kawakubo

In 1982 Kawakubo shows her revolutionary autumn–winter collection Holes (also known as Destroy) in Paris.

Throughout the 1980s, Japan undergoes a series of major economic and sociocultural shifts. With a booming ‘bubble economy’, the country becomes increasingly more open to international creative influences. Simultaneously, Japanese technology and culture – such as the Sony Walkman, video games, anime and manga – make a significant impact overseas.

By the early 1980s, Comme des Garçons has a cult-like following across Japan, with 150 franchised shops, eighty employees and revenues of thirty million US dollars per year. The brand’s followers become known as karasu-zoku (crow tribe), named for their penchant for black clothing.

In 1981 Kawakubo, alongside Yohji Yamamoto, makes her Paris runway debut. This and her subsequent collections of loose-fitting, distressed, layered and asymmetrical clothing contrast with the feminine silhouettes that dominate the runways of the decade, leading critics to dub Kawakubo’s work ‘anti-fashion’.

1990s

Westwood

In 1990 Westwood presents her Portrait collection, photographed here by Robyn Beeche. Westwood is heavily inspired by the collection of eighteenth-century oil paintings and decorative arts housed in the Wallace Collection, most famously expressed in her corsets featuring François Boucher’s Daphnis and Chloe, 1743.

In the 1990s fashion takes a turn towards minimalism, with designers like Calvin Klein and Miuccia Prada popularising the slip dress.

Westwood embraces theatricality and maximalism. Drawing on sources ranging from Rococo art to historical British dress, she questions, deconstructs and reimagines her references. This process of exploration finds expression in Westwood’s production of hyper-feminine, exaggerated silhouettes, such as the 9-inch (22 cm) ‘super-elevated gillie’ platform shoes debuted in her 1993 Anglomania collection. Westwood’s key innovations in the 1990s also include using traditional Scottish tartan and remaking the corset as outerwear.

Westwood’s contributions to British dress and culture are formally recognised throughout the decade. In 1990 and 1991, Westwood is named British Fashion Council’s British Designer of the Year. In 1992 she receives an Order of the British Empire (OBE) from Queen Elizabeth II.

Kawakubo

In 1994 Kawakubo echoes grunge aesthetics in her collection Metamorphosis, which features ragged, tattered designs. The garments are created using boiled woollens that are shrunk after construction.

Like Westwood, Kawakubo’s 1990s collections stand in stark contrast to dominant trends in mainstream fashion.

Questioning limited definitions of beauty and taste, Kawakubo experiments with atypical fabrics and the language of deconstruction. In collections like Lilith, 1992, Synergy, 1993, and Metamorphosis, 1994, she explores fabric manipulation, pattern-making and lurid colour. Many of her collections also question garment function and associated gendered conventions. Kawakubo also continues to experiment with form, most notably in her infamous 1997 collection Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body, which blurs the line between body and garment.

Kawakubo’s services to fashion are acknowledged with several honours during this decade. In recognition of her contributions to furthering the arts in France and beyond, she is awarded the prestigious Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Minister of Culture in 1993.

2000s

Westwood

In 2000 model Kate Moss – a close friend of Westwood – is famously photographed by paparazzi wearing original Pirate collection boots.

In line with the rapid technological and cultural developments of the new millennium, the 2000s for Westwood are marked by significant growth and change. According to her biographer Ian Kelly, there is a ‘Vivienne Westwood assault on mainstream consciousness’: her designs are increasingly worn by significant figures in popular culture, including actors Sarah Jessica Parker, Kate Winslet and Pamela Anderson and fashion model Kate Moss.

Simultaneously, Westwood grapples with reconciling the commercial success of her company with her growing concerns about the overconsumption and waste prevalent in the fashion world. In 2007 she publishes her manifesto, Active Resistance to Propaganda, and begins a period of tireless campaigning for humanitarian causes and environmental sustainability.

In 2002 a capsule collection developed by Westwood and Kawakubo is realised. The collaboration features Westwood designs produced in Comme des Garçons fabrics.

Kawakubo

Kawakubo’s 2009 Wonderland collection features childish illustrations and surreal or trompe l’œil effects.

Throughout the 2000s, Comme des Garçons undergoes significant expansion, particularly through Kawakubo’s embrace of highly experimental and unconventional retail environments.

Comme des Garçons marks its fortieth anniversary with a secondary clothing line titled BLACK. Launched during the 2008 global financial crisis, BLACK offers a selection of the most popular designs from the label’s archive at a lower price point.

Despite the brand’s expansion through these retail experiments and limited collections, Comme des Garçons’ mainline runway collections remain Kawakubo’s purest mode of artistic expression. She continues to explore form and function and unorthodox working methods in service of her unique design lexicon.

2010s

Westwood

Westwood presents her spring–summer 2019 collection virtually, with an online lookbook and short film.

Throughout the 2010s Westwood continues to harness her influence to raise awareness about the effects of climate change. In 2010 she launches her Climate Revolution project at the Worlds End storefront on King’s Road. She also aligns herself with and becomes a spokesperson for prominent international NGOs, including Greenpeace and Cool Earth, committed to protecting the natural environment.

Many of Westwood’s collections from this decade blur the line between fashion and activism, with models wearing garments with messages pertaining to political corruption and the climate crisis, and runways being transformed into protest marches. Beyond these more visible displays of her politics, Westwood also begins to consider alternative modes of manufacturing and presenting her collections, examples of which include working with the Ethical Fashion Initiative to connect with artisans based in Nairobi and replacing runway presentations with short films.

Kawakubo

Kawakubo backstage at the Not Making Clothing runway presentation, 2013.

Kawakubo’s runway presentations in the 2010s feature increasingly abstract and sculptural forms. This shift is articulated by the designer in an October 2013 article published in System magazine (reproduced and on display nearby) that coincides with the presentation of Comme des Garçons’ spring–summer 2014 collection, Not Making Clothing:

In order to make this collection, I wanted to change the usual route within my head. I tried to look at everything I look at in a different way. I thought a way to do this was to start out with the intention of not even trying to make clothes. I tried to think and feel as if I wasn’t making clothes.

This sets the tone for her design practice into the present day.

Kawakubo, quoted in System, no. 2, autumn–winter 2013.

2020s

Westwood

Entering her final decade, Westwood continues to use her brand and profile to advocate for political and environmental causes. In 2020 she protests imprisoned WikiLeaks founder and free speech activist Julian Assange’s possible extradition to the US, suspending herself in a giant birdcage outside the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales in London. In 2022 she designs the outfits for Assange’s wedding to Stella Moris in Belmarsh Prison.

Westwood peacefully passes away on 29 December 2022. An official statement reads: ‘Vivienne continued to do the things she loved up until the last moment … changing the world for the better.’

Kawakubo

From 2020 Kawakubo’s collection titles become more explicit, providing insights into her values and concerns. Her stated approach is to look inwards for inspiration and meaning, and each collection is a creative expression of her emotional state and response to global affairs. Smaller is Stronger, Kawakubo’s autumn–winter 2025 collection, is a critique of corporate dominance and patriarchal systems, while After the Dust, her spring–summer 2026 collection, is a meditation on the beauty of imperfection.