NGV Magazine: Visitors to Westwood | Kawakubo will encounter an immersive archival display illuminating the careers of both designers. Tell us how this project came about and what visitors can expect?’

Charlotte Botica (CB): Our aim for the Westwood | Kawakubo timeline and archive was to provide rich contextual and scene-setting to allow audiences to become acquainted with the lives, personalities and creative practices of Vivienne Westwood and Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons. Upon entering, a video presentation of footage that captures 1970s–90s in London and Tokyo is interspersed with early runway presentations and television coverage of the designers. The accompanying soundtrack features reflections from fashion journalist Suzy Menkes and fellow designers Rick Owens, Bella Freud and Pharrell Williams on the influence and impact Kawakubo and Westwood have had on them and the fashion industry at large. It was also important for us to foreground Westwood and Kawakubo’s own perspectives: visitors will be able to read large quotes from each designer that reveal their views on fashion and creativity.

In the second part of the timeline, a selection of imagery, archival materials and footage documents important moments in their respective careers, in the context of broader social and cultural movements. For Westwood, examples of these iconic moments include the first issue of Deluxe magazine from 1977, which features an editorial for her shop Seditionaries; a photograph of Naomi Campbell tumbling on the runway in 9-inch platform heels during the 1993 Anglomania collection presentation; and the original pattern pieces for the crown designed by milliner Stephen Jones for the 1987 Harris Tweed collection. For Kawakubo, we show a rare early press book for her 1986 Bonding collection, photographed by Steven Meisel; footage of the costumes based on her seminal 1996 collection Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body she designed for American choreographer Merce Cunningham’s Scenario; and a campaign poster photographed by Cindy Sherman for the 1994 Eccentric collection.

NGV: You found so much rich material to work with. Where did you start when conceiving the display?

Meg Slater (MS): Both Westwood and Kawakubo were born in the 1940s and established their careers as fashion designers in the 1970s. When you have more than eighty very rich years of life to represent, it is important to establish three things: key moments, the level of detail, and points of synergy between the designers. To determine the key moments in the designers’ lives and careers, we found it best to cast the net wide and then refine. We started the research process by collating a comprehensive timeline of key events for each designer – from the years they attended university and the years seminal collections were presented to the years they received prestigious awards. From there, we closely reviewed and isolated the key moments to represent and determined how they should be represented (through written text, photography, video or archival materials).

We also established early on that it would be useful to contextualise these moments in each designer’s career by referencing broader social and cultural developments. These range from the lasting impact of WWII in Japan and the UK (where Kawakubo and Westwood where raised, respectively) and the advent of online shopping, to the cultural impact of figures like Diana, Princess of Wales and model Naomi Campbell in and beyond the fashion world. During the research process, several points of synergy between the designers were revealed, and we have integrated a selection of these moments throughout the timeline. An early example is Kawakubo (accompanied by fellow fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto) visiting Westwood’s King’s Road store in the 1970s. More recently, both designers published creative manifestos just six years apart (Westwood published her Active Resistance to Propaganda manifesto in 2007, and Kawakubo published her manifesto in a 2013 issue of System magazine). Each manifesto sets out the focus and aims of their creatively and socially motivated practices in the years to come. Finally, and from a more practical perspective, we worked closely with NGV graphic and exhibition design teams to develop a timeline that met the spatial requirements of the exhibition space.

NGV: Can you take us through your research process? How did you find information, sources and material?

CB: Instead of creating a text-only timeline, we gathered a range of materials, spanning images, sound, performance and publishing, to create an immersive environment evoking the look and feel of the times in which the designers were working. Once we had compiled a comprehensive understanding of Westwood and Kawakubo, we then determined the digestible volume of information for inclusion. For the video wall we accessed archival footage that captured the cultural Zeitgeist of 1970s Tokyo and London, respectively. These snapshots reveal the street styles and popular fashions during the designers’ early careers. For example, footage of white-collar workers exiting London’s Piccadilly Circus train station is juxtaposed with footage of punks and teddy boys parading the streets around London.

In the second part of the timeline, audiences are presented with materials produced by the fashion houses and which are now housed in the NGV Archive. Copies of magazines such as i-D, Purple and The Face highlight the significance of publications before the rise of digital and social media marketing, so it was essential to include these materials. Such publications, particularly in the 1980s–90s, were at the forefront of showcasing emerging and independent fashion. A few items also came from eBay, such as the publication from the year 2000 dedicated to Kawakubo’s Harvard University Excellence in Design Award and a Vivienne Westwood Climate Revolution T-shirt from c. 2012–13 with graphic messaging pertaining to the climate crisis. Items like these add great texture to the timeline.

NGV: What role have advertising and publishing played in the designers’ practice?

CB: For Kawakubo, publishing and advertising are an extension of Comme des Garçons’ brand identity and her broader creative practice. She sees no hierarchy in the brand’s outputs. From the beginning she worked with key photographers on largely black and white press books and editorial images. From 1988 to 1991, Comme des Garçons published Six magazine, an eight-issue experimental magazine comprising new and archival photography, images of interiors and architecture, and work by contemporary artists. Issues rarely featured Comme des Garçons collections but were a sensory and visually arresting experience. The editorial team was composed of Kawakubo, editor Atsuko Kozasu and artistic director Tsuguya Inoue, who said of Six: ‘This is our world. We think it’s beautiful. Join us if you feel the same way.’ In the timeline we feature the first issue, published in 1988, which includes contemporary artworks by Gilbert and George and André Kertész and articles on pioneering Irish designer Eileen Gray and French avant-garde artist, director and writer Jean Cocteau. A video screen reveals the contents of the sixth issue, released in 1990, flipping through the pages to show an editorial spread shot in Tbilisi, Georgia, inspired by painter Niko Pirosmani, featuring locals wearing a mixture of Comme des Garcons clothing and Georgian traditional dress.

We also highlight a copy of System magazine from October 2013 featuring the manifesto that Kawakubo released to coincide with the presentation of her spring–summer 2014 collection, Not Making Clothing, which marked a shift in her practice towards increasingly abstract designs. ‘I tried to look at everything in a different way,’ Kawakubo states in her manifesto. ‘I thought a way to do this was to start out with the intention of not even trying to make clothes.’

MS: Publishing and advertising have played a similarly significant, albeit quite different, role in representing Westwood and her brand. Beyond the name of her eponymous brand, Westwood embedded her image and her values into everything she made. From her earliest collaborations with Malcolm McLaren in the 1970s, through to her final collections before her passing in 2022, she remained at the forefront, whether on the cover of a magazine or walking the runway alongside models and friends wearing her designs. Despite Westwood’s front-facing presence in her brand’s operations and output, it is important to acknowledge shifts in her approach to communicating her vision and values.

Westwood’s imaging of her brand in the final decades of the twentieth century is characterised by her bold, often humorous integration of the source material that inspired her designs. A key example is the invitation to the runway presentation of her 1993 Anglomania collection, which will be on display in the timeline. For the invite, she appropriated a sixteenth-century depiction of Queen Elizabeth I by placing a gold safety pin through the monarch’s lip. This aptly captured Westwood’s celebration and subversion of English fashion and cultural history in the looks that comprised the collection. This lightness is also represented in the campaigns and promotional materials centring British model Sarah Stockbridge, who first became Westwood’s muse for her 1987 Harris Tweed collection. Westwood saw Stockbridge as the embodiment the classic ‘English rose’ archetype, but with a modern twist – as embodied in the celebrated cover for the fiftieth anniversary of i-D Magazine, also included in this timeline.

By contrast, in the 2000s, Westwood’s brand and her public image underwent significant transformation, and Westwood began to occupy a new, expanded space in popular culture. This can be attributed to many factors, from the rise of online marketing to celebrities like Sarah Jessica Parker and Pamela Anderson wearing Westwood’s designs. Throughout this period of change, Westwood always voiced her complicated feelings about the space she occupied within the fashion industry. She shared her struggles reconciling her values and politics with the brand’s rapid growth amid a mounting climate crisis. She regularly articulated her concerns and hopes for change within her industry, most notably in her Active Resistance to Propaganda manifesto, published in 2007, a copy of which will be on display in the timeline. Beyond this text, she began to harness every opportunity – from collection titles and runway presentations to manufacturing methods – to more closely align her output with her ethics.

NGV: What does this kind of archival presentation add to an exhibition like Westwood | Kawakubo, and to archives in art museums more broadly?

MS: I think archival displays can play a crucial role in contextualising and making accessible the life and practice of a creative person. The NGV, like all public institutions, welcomes a diverse audience, so it is important to provide multiple levels of entry into a subject. This might be through the artworks or designs themselves, the wall texts accompanying them, as well as talks and tours, workshops, or additional layers of archival information that help to situate audiences in a time and place.

Galleries and museums can be intimidating, especially if you feel there is certain level of knowledge required to appreciate an exhibition or collection display. We kept this front of mind when developing the timeline in this exhibition, and it is part of the reason why we applied a broader lens to our subjects. Rather than simply recounting the career milestones of Westwood and Kawakubo, we contextualised the development of their practices as designers, in and beyond the fashion world. For example, to represent the conditions that led Westwood and Kawakubo to pursue fashion design, we firstly describe and illustrate post-WWII society in Japan and the UK, the emergence of countercultural movements including feminism and gay rights, and other major historical developments that shaped the fashion industry of the 1960s and 1970s.

In the twenty-first century, fashion undergoes significant changes amid the rise of online shopping and the advent of fast fashion. Both Westwood and Kawakubo rebel against many of these dominant trends by exploring alternative design methodologies, modes of production, promotion and retail. Without representing these broader sociocultural shifts, the significance and impact of the unconventional ways of working that have established Westwood and Kawakubo as fashion visionaries would not be clear. Further, these developments are more widely known and experienced by exhibition visitors and can provide a point of entry into a more specific subject.

NGV: Did you find any surprises or new discoveries along the way?

MS: Prior to working on this project, I was aware of Kawakubo’s collaborations with artists, but I hadn’t appreciated the full extent of her engagement with art history. It is a throughline that connects the many arms of Comme des Garçons. Kawakubo has crafted collections referencing mythological figures like Lilith (Adam’s first wife, who in Jewish folklore, was banished from Eden for refusing to ‘lie beneath’ him) and the avant-garde practice of twentieth-century queer French artist and writer Claude Cahun.

Since opening her first store in the Minami-Aoyama district of Tokyo in 1976, which did not have any mirrors or window displays, Kawakubo has prioritised creating unique, alternative retail models and environments. This has often been achieved through collaborations with leading architects and artists, which has seen the constant reimagining of Comme des Garçons stores across the globe. This innovation is also reflected in the unconventional promotional materials produced to support Kawakubo’s collections, which are printed and often comprise source imagery spanning many disciplines, from photographs by Peter Lindbergh to sculptures by Ai Weiwei.

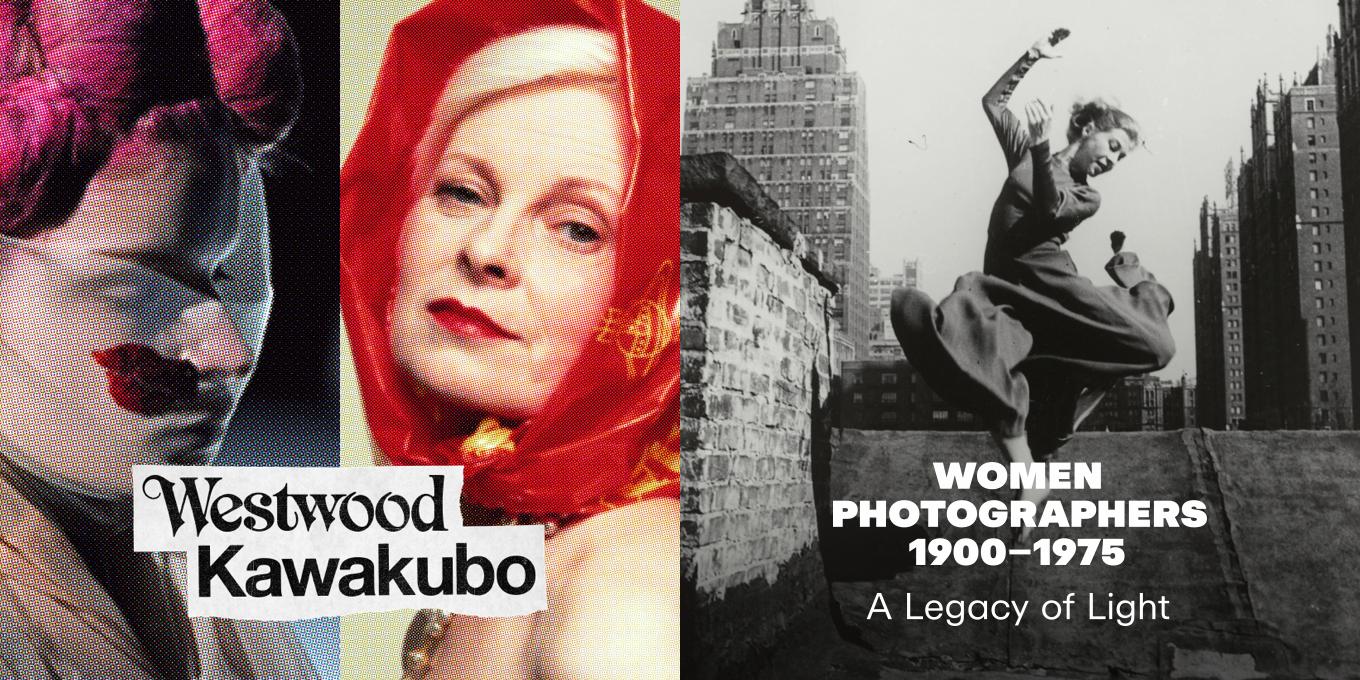

In the exhibition timeline, we have taken the opportunity to spotlight some of the interdisciplinary artistic collaborations undertaken by Kawakubo for Comme des Garçons. We are thrilled to include examples of Kawakubo’s collaborations with renowned artists like photographer Cindy Sherman and choreographer Merce Cunningham. I am also excited for visitors to see lesser-known items like the experimental program Kawakubo produced with Raw Vision, a journal dedicated to outsider art, to accompany Comme des Garçons’ MONSTER collection, autumn-winter 2014.

CB: Audiences might be surprised by Kawakubo’s association with celebrities and artists, with past Comme des Garçons campaigns featuring the likes of actors John Malkovich and Sandra Bernhard. In 1986 the New York artist Jean-Michel Basquiat walked for the menswear line Comme des Garçons Homme – the timeline features footage of Basquiat walking the runway wearing a grey double-breasted suit. Another moment to keep an eye out for is a postage stamp featuring an outfit from Vivienne Westwood’s’ 1993 Anglomania collection, released in 2012 for the Royal Mail’s Great British Fashion Stamp series. The stamp is a reminder of Westwood’s enduring influence and impact on the fashion industry, as someone who was once an outsider, provocateur and disrupter became part of the establishment.

Audio Description and Touch Tour

Audio Description and Touch Tour