The music of Gustav Mahler acts as a bridge from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, just as Beethoven’s music before him acted as a bridge from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century.

Gustav Mahler was one of 14 children born into a humble family in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). From the age of four, his musical talent was encouraged and he was regarded as a Wunderkind.

Following his graduation from the Vienna Conservatory, Mahler conducted orchestras throughout Germany and the Empire. Eventually he converted to Catholicism (as did many Jews) to secure the Court appointment to the Hofoper (Vienna Opera House), assuming the role of artistic director in 1897.

Revolutionising opera

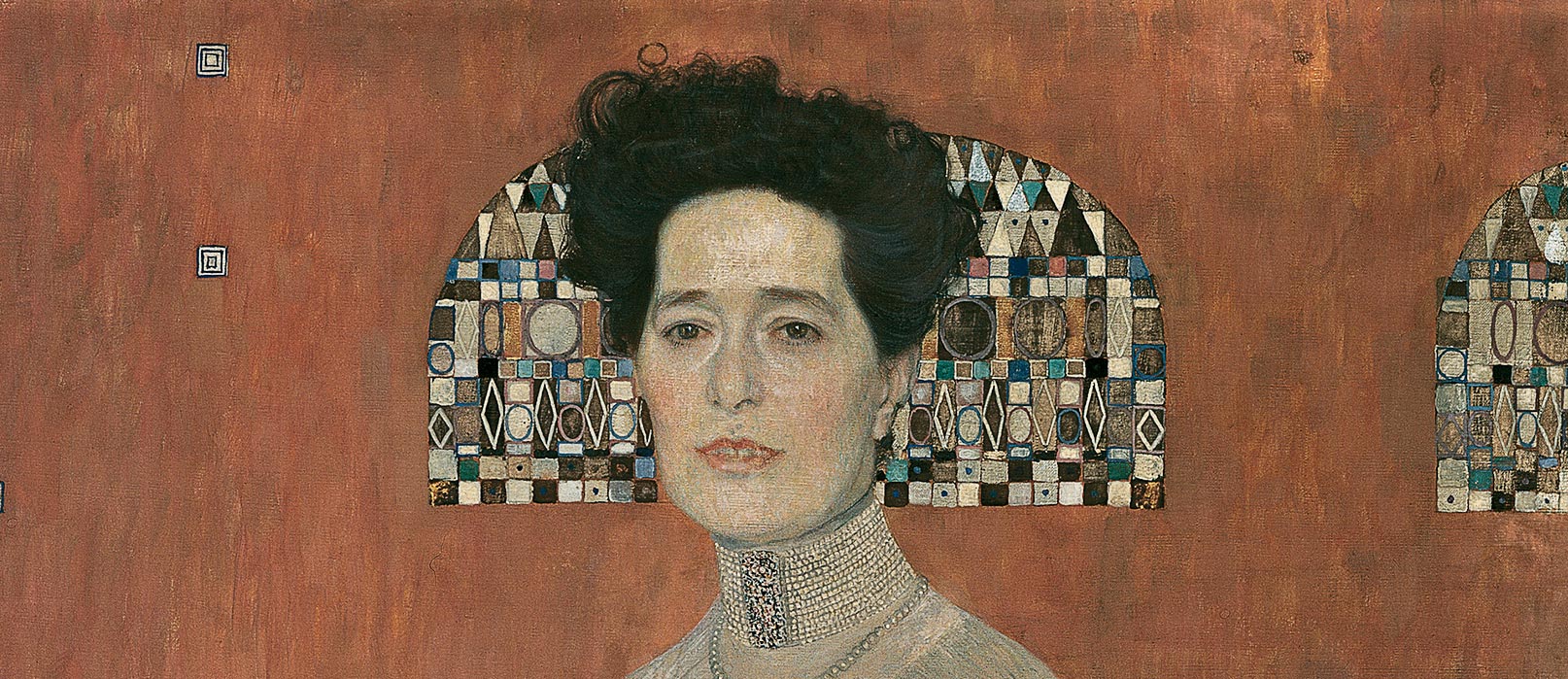

In his decade as the Hofoper’s supreme director, Mahler revived the great classics and revolutionised the staging with Secessionist artist Alfred Roller as his set, costumes and lighting designer, thus bringing opera into the modern era.

He also insisted on exacting standards from performers, decrying the ‘sloppiness’ of players and singers; this was openly resented, as was his ‘Jewishness’.

Mahler eventually resigned in 1907, leaving for New York to direct its Metropolitan Opera and subsequently the newly-constituted New York Philharmonic, reshaping and transforming it into a leading orchestra.

Mahler and Vienna

When Mahler left Vienna in 1907 he described his decade at the Hofoper as ‘ten war-years’. And in a letter to Mahler, fellow composer Arnold Schoenberg referred to ‘our hated and beloved Vienna’.

For it was, as Michael Kennedy writes in The Master Musicians: Mahler, ‘the city of light-hearted, easy-going, gracious living, of intrigue, callousness and spite where revolutionary ideas in art struggled for expression in a climate of conservative, sometimes reactionary, opinion.’

Artistic process

For Mahler, artistic creation – particularly the creation of his own vast and complex music – was an encounter with both natural and supernatural forces rather than a purely technical process.

While rehearsing for the premiere of his 5th Symphony, Mahler wrote to his wife: ‘That scherzo is an accursed movement! … How should [audiences] react to this chaos, which is constantly giving birth to new worlds and promptly destroying them again? What should they make of these primeval noises, this rushing, roaring, raging sea, these dancing stars, these ebbing, shimmering, gleaming waves?’

Belated recognition

Though Mahler was well received as a composer in Germany and in parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, his 9th Symphony was the only one to have a world premier in Vienna – just over a year after his death.

It was some 50 years before he was recognised as the last of Vienna’s great symphonic composers. His song cycles (Songs of the Wayfarer, Kindertotenlieder and Das Lied von der Erde) are equally revered.