Level 5-12

This resource explores some big ideas in contemporary art and design through the work of NGV Triennial artists, with a particular focus on the cross-curricular priorities and capabilities in the Victorian curriculum (sustainability, Asia and Australia’s engagement with Asia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures, critical and creative thinking, intercultural and ethical understanding).

It focuses in detail on ten artists and designers and includes questions, activities and resources that can be used with students both during and after a visit to the exhibition to promote critical and creative thinking about art, design and how we live, think and connect with each other. A number of the artists featured here are also included in the NGV My Contemporary Art Book designed for younger audiences.

Watch

Meet the artist – Tom Crago

Meet the designer – PET Lamp/Bula’bula artists

Meet the artist – Hahan

Meet the artist – Pae White

Teachers Notes

-

MEET THE ARTIST/DESIGNER – Guo Pei

Guo Pei is China’s most famous designer of haute couture, or made-to-measure fashion. She has created unique designs for China’s rich and famous for over twenty years, but came to global attention in 2015 when one of her creations was worn by Rihanna to the Met Ball, the annual fundraising gala held for the benefit of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute in New York City. The gown – a canary yellow floor-length dress with a large circular train, edged with yellow-coloured fur and embroidered with silver floral patterns – weighed 25 kilograms and took 100 workers 50,000 hours to create. Inspired by the splendour of Imperial China, it propelled Guo Pei to international fame.

Guo Pei (born 1967) graduated from the Beijing School of Industrial Fashion Design in 1986, having completed a four-year design program that included drawing, sketching and pattern making. After ten years designing for major manufacturers, Guo Pei founded Rose Studio, her own label and atelier, in 1997. In 2008 she was selected to design the ceremonial dresses for the Beijing Olympics. She recently opened a second atelier in Paris.

Inspired by her grandmother’s descriptions of the exquisite garments and fabrics of her youth, Guo Pei taught herself many of the artisanal skills used in her work, traditions lost during China’s Cultural Revolution, when they were considered out of step with the ideology of the regime. Today she employs nearly 500 artisans to help produce her garments, which can take thousands of hours to create.

The NGV Triennial features the 2017 spring−summer couture collection, Legend, which took two years to create using the skills of more than 300 embroiderers and 200 designers, pattern makers and seamstresses. The collection was first presented at La Conciergerie, the building where Marie Antoinette, the last Queen of France, was imprisoned and beheaded. Marie Antoinette’s story infuses the collection, which was initially inspired by the history of the missionaries, craftspeople and artists who worked within the Abbey of Saint Gall in Switzerland. Almost all of the fabrics in the Legend collection were manufactured in the town of Saint Gallen, known for its textile manufacturers and embroiderers. When the collection debuted the show opened with Luminous spirit, 2017 a garment made from phosphorescent fabric that glows ghost-like, evoking the spirit of the eighteenth-century queen. It concluded with Red goddess, 2017, a deep red robe of silk woven with fine metal fibres, modelled by 86-year-old American model Carmen Dell’ Orefice.

Questions for students

What mood or feeling do Guo Pei’s designs create? How does she do this?

What materials and techniques does Guo Pei use in this collection?

Choose one garment from the Legend collection and describe how Guo Pei’s inspiration and influences can be seen in it.

The Legend collection is haute couture – high fashion not intended for everyday wear. How might these designs be adapted for a ready to wear collection?

Create

Guo Pei’s influences are evident in the Legend collection; she has translated her inspiration into wearable art. Find images of the things Guo Pei has been inspired by and note how she has adapted her ideas from her original inspiration. Find a building that inspires you – the architecture, any stories about the building or its occupants – and turn your inspiration into a garment design!

MEET THE ARTIST/DESIGNER – Tom Crago

Tom Crago (born 1976) is the owner and CEO of video game developers Tantalus and Straight Right, companies that have produced games such as Cars, Need for Speed, Sponge Bob and Spyro the Dragon as well as the Mass Effect and Deus Ex series. Crago has degrees in Arts, Law and International Business and has previously worked as a media lawyer. He has founded and run companies in the health, fashion and new media industries, and has produced short films and written for film, print, stage and television. He is currently completing a PhD in art, video games and philosophy. Crago has also represented Australia in the sport of athletics.

For the NGV Triennial Tom Crago has collaborated with numerous sound and visual artists to create a virtual reality experience called Materials, 2016–17. The game transports us onto a ship and we are asked to journey through the virtual space, discovering its possibilities, to generate our own artwork. As we undertake the journey we are surrounded by ambient sound, created by sound designer David Shea, and we discover pieces of an artwork by Viv Miller that combine into the player’s own composition.

Questions for students

For secondary school students

Virtual worlds and the objects encoded within them are first imagined and then designed … Through literature we can imagine the virtual, through art and design we can visualise the virtual, and through computer-enhanced technology we are beginning to literally experience the virtual, which is giving us glimpses into other worlds, including that of the future. But let us not forget that creativity will always power the human imagination – our ultimate virtual reality machine.

Simone LeAmon

(NGV Triennial 2017 Ewan McEoin, Simon Maidment, Megan Patty, Pip Wallis, editors and contributors pp 275)

Think

Describe your experiences on the virtual ‘ship’. What happened on your journey? How did you respond? What did you see, hear, feel?How is the virtual reality experience of the ship different to reading a story (literature) or seeing a picture or film (art and design) about a ship’s journey?

How is the virtual reality experience different to a real-life experience?

In what ways might virtual reality be used as a tool in the future?

What might be some of the advantages and pitfalls?

What ethical considerations might be involved?

What might be the effects of extended time spent in virtual realities? Consider depersonalisation (losing a sense of our physical bodies) and desensitisation (losing emotional connection to others and our real surroundings).

To what extent is the experience of the work subjective and to what extent is it controlled by the artist(s)?

What might have inspired this artwork? What do you think the creator wanted participants to experience?

What aesthetic considerations or choices have been made by the artist? What is the effect of these?

Create

Imagine that the ‘ship’ is a metaphor for your mind and your experiences in the ship are your inner life – the journey you take inside your mind. What rooms and pathways would there be? What hopes, dreams, fears, obstacles, challenges or conflicts? Describe the journey your ‘ship’ is taking with drawings and text. Make a simple animation of your drawing using an animation app like iMotion or draw a ‘mind map’.

Write a descriptive piece that paints a picture of an aspect of your journey – either the virtual journey or your metaphorical mind journey.

Write a poem that captures your sensations while participating in the artwork. Draw on your senses and consider what you saw, felt and heard. What you would be able to smell? What would the different surfaces feel like to touch?For primary school students

Create

Imagine you are going on a sea voyage. Draw a picture of the ship that will take you on your journey. What is it made from? Does it have sails? An engine? Fins? Propellers? Is it powered by dolphins or mermaids?

Who are your fellow travellers? Draw their portraits.

Draw a view from the porthole (window) of your cabin.

Draw a map of the countries you will visit. (They might be real countries, or you could invent your own.) On your map, draw some pictures of the things you encounter – buildings, treasures, monsters, hazards.

Use Minecraft to make your world come to life.

Animate one of your creatures or characters using an app like Puppet Pals or Chatterpix.

Write a diary for a week of your journey. What adventures do you have?

After you have experienced Materials, complete a (Looks like/Feels like/Sounds like) Y chart. Turn your Y chart words into a poem. Then write an epic ode – a poem that tells the story of your trip.

MEET THE ARTIST/DESIGNER – Joris Laarman

Joris Laarman (born 1979) is an innovative Dutch designer, artist and entrepreneur best known for his experimental designs inspired by science and emerging technologies. In 2004 he launched Laarman Lab with his partner, filmmaker Anita Star. Laarman Lab – a multidisciplinary team of scientists, designers, engineers, computer programmers and craftsmen – uses cutting-edge technology and manufacturing processes to create designs that push the boundaries of possibility. Laarman’s work has included the world’s first open-source 3D printed chair; furniture developed from algorithms that emulate the complex growth of trees and bones; and a living lamp made out of bioluminescent hamster cells enriched with firefly genes.

Laarman Lab and its offshoot MX3D have developed plans for the world’s first 3D printed bridge that will be built across an Amsterdam canal using robotic printers.

Questions for students

Describe how each of Joris Laarman’s designs reflect the forms of nature.

How might the technologies developed by Laarman Lab be used in the future?

Find out more about Laarman Lab and MX3D Printing:

Joris Laarman Lab: Design in the Digital Age

3D Printed Chair by Joris Laarman – Ultimaker: 3D Printing Story

MEET THE ARTIST/DESIGNER – Kushana Bush (Analytical frameworks)

Kushana Bush (born 1989) lives and works in Dunedin, New Zealand. Bush produces delicate gouache paintings on paper that reference Persian miniatures, illuminated manuscripts and European art history, blending imagery from different places and times to comment on the present.

Her dense compositions are alive with colour, pattern and movement. At first glimpse, they are filled with drama, pageantry and animated human interaction. On closer inspection, they reveal disquieting scenes of human folly.

VCE ART – ANALYICAL FRAMEWORKS

Analytical frameworks are a lens through which we can look at works of art and design to give us different perspectives and expand our understanding.

Within the VCE Art Study Design we use the Structural, Personal, Cultural and Contemporary Frameworks:

The Structural Framework is used to analyse how the style, symbolism and structural elements of artworks contribute to the meanings and messages conveyed.

The Personal Framework is used to discuss how a work of art might reflect the artist’s personal feelings, thinking and life circumstances and how the viewer’s interpretations of the work are influenced by their own life experiences.

The Cultural Framework is used to identify the influence on an artwork of the context of time, place and the society in which it was made.

The Contemporary Framework is used to interpret how contemporary ideas and issues influence the making, interpretation and analysis of artworks from both the past and present.

KUSHANA BUSH, The ones behind this, 2015

Structural framework

Kushana Bush’s The ones behind this, 2015, depicts a crowd gathered about a table cum stage, under a white pavilion in front of a high, patterned wall. Pipers play their instruments in unison to the left, while on the right figures strive to turn and support a large spoked wooden wheel. Dangling suspended by one leg from a rope in the centre is a deer, its eyes open and hooves delicately pointed. Some of the figures, tongues out, strain towards the deer to lick it.

The massed bodies – a mixture of sexes, ages and cultures – engage in a timeless ritual of celebration with an air of desperate absurdity. Muted colours unify the busy composition, which, like the wheel, draw the eye around the circle of human drama. In the empty space on the stage stand three blue and white ceramic vessels, incongruous and static in the human throng.

The symbols of sacrifice (the deer), celebration (music, flags, feasting), culture (pots and tiles), control (the wheel) and destiny (the wheel of fortune) imply that we are all swept along by forces beyond our control.

The figures are piled up high, close to the top of the picture plane, putting the viewer squarely inside the chaotic activity.

Cultural framework

Kushana Bush’s works draw influence from many artistic traditions to comment on contemporary society and current affairs:

KB: Who are the ones behind all this carnage? Not me, we say, pointing to others, yet we know that in our inaction, we are also responsible.

This work was painted in 2015, but a painting speaks across time, and since then we’ve become all too familiar with bunting, fanfare and mob mentality at the surreally televised Trump rallies.

Here the dignified musicians play on, despite the carnal tide who wrestle control with what they think is a steering wheel. Perhaps it is just a symbolic wheel of life, whose turn next?

In the age of digital media, the 24-hour news cycle delivers local and international news directly and relentlessly. Politics becomes theatre and human drama of unimaginable scale and tragedy is reduced to sound bites and stories. Bush observes our own era in the timeline of human history and suggests that we have not advanced very far.

Personal framework

Kushana Bush is inspired by art from the past and from different cultures and traditions, but the characters in her work are inspired by her reaction to the world events she hears unfolding as she works.

KB: The faces and their multiplicity of expressions could be any single person’s reaction to one event. Shock, sadness, pity, anger, spite, we oscillate between these reactions to a single current event all in a 24-hour news cycle. I notice these feelings as I’m painting a single painting over the course of a few months. What I started out feeling towards a single news story is never what I finish with.

Bush describes her work as a way to come to grips with the world.

KB: The real world is full of failure and discontent. In my little painted world, I get to play god. That’s very empowering. I think the tragi-comic is a useful term to describe them – the paintings challenge us to laugh or be doomed

(http://pantograph-punch.com/post/interview-with-kushana-bush)

Contemporary framework

These descriptions capture Bush’s ability to draw from the iconic imagery and style of past traditions to express both the grand narratives and the personal complexities of modern life. Her visual language is fresh and witty, young and wise, quoting contemporary culture as well as that of the past.

In a digital age, Bush eschews technology to use processes that involve time, precision and manual skill. She works exclusively in gouache. Her technique involves tracing multiple drawings and then painting in a medium that doesn’t allow room for error.

Questions for students

Structural framework

How does Bush’s manipulation of scale affect the work? How does Bush use space and depth? How is symbolism important in the work?

How does the artist’s style affect the way you interpret the work?

How do Bush’s techniques and processes add to her work?

How are Bush’s influences – Persian miniatures and Japanese prints – evident in her work?

Cultural framework

What contemporary ‘carnage’ is Bush referring to in her comment?

How important is the artist’s commentary for understanding this work?

In what other ways might this work be seen to represent the time in which it was made?

Personal Framework

Find out more about Kushana Bush

What personal associations does Bush’s work hold for you? What cultural references do you recognise? How do these affect your interpretation of the work?

How is humour used in Bush’s work?

How important is it that the viewer understand her artistic and cultural references?

Contemporary framework

What contemporary ideas are evident in Bush’s paintings?

What might be the ‘contemporary anxieties’ referred to by David Eggleton?

Create

Find some examples of Persian miniature painting. Observe and describe the artists’ composition and use of colour and space.

Make your own miniature painting in gouache, inspired by an historical painting and an aspect of current affairs.

MEET THE ARTIST/DESIGNER – PET Lamp/Bula’bula artists

PET Lamp, in close collaboration with local indigenous artists, co-design unique, handwoven lampshades that reuse PET plastic bottles.

The PET Lamp project began in 2011, when industrial engineer Alvaro Catalan de Ocón took part in a project focused on the reuse of PET (polyethylene terephthalate) plastic bottles as a way to address the issue of plastic waste affecting the Colombian Amazon.

The PET bottle is a product with a very short lifespan but it takes decades to decompose. Billions of PET bottles are produced each year, and their disposal is a global environmental problem. By merging local Colombian weaving techniques with industrial lighting design, Alvaro created a new purpose for the plastic bottle. The project began as a way to raise awareness of the overuse of plastic bottles, and has evolved as a means to highlight the value of different indigenous or traditional weaving practices and their role in preserving culture and community, knowledge and tradition. As well as celebrating these traditional practices, a design collaboration such as that with the PET Lamp project offers communities an avenue for generating ongoing income. The project has worked with artists in Colombia, Chile, Ethiopia and Japan.

For the NGV Triennial the PET Lamp project formed a partnership with Bula’bula artists from the community of Ramingining in North East Arnhem Land. Bula’bula Arts is an Aboriginal owned and governed, not-for-profit organisation that aims to preserve and foster Yolngu culture.

The Bula’bula weavers (with name, language group) were: Lynette Birriran, Djambarrpuyungu, born 1960; Mary Dhapalany 1, Mandhalpuy, born 1950; Judith Djelirr, Liyagalawumirr, born 1950; Julie Djulibing Malibirr, Ganalbingu, born 1948; Joy Gadawarr, Dabi, born 1960; Melinda Gedjen, Liyagalawumirr, born 1973; Betty Matjarra 1, Garrwura, born 1949; Cecily Mopbarrmbrr, Marrangu, born 1995; Evonne Munuyngu, Mandhalpuy, born 1960.

Yolgnu women have a strong tradition of weaving. Objects such as fish traps and nets, mats, string bags, baskets and dilly bags are traditionally made using materials harvested from plants such as pandanus, sandpalm and kurrajong, and coloured with natural dyes.

For the NGV project the Ramingining weavers created a large installation in which individual stories are woven together in a work that reflects both the landscape and kinship connections.

Questions for students

Look at the project created by the Bula’bula artists. How does it reflect the landscape and culture of the artists?

In what ways is the Ramingining project similar to and different from the other PET Lamp projects?

Is the project effective in raising awareness of the problem of PET plastic? In what ways?

Design your own art project to raise awareness of the issues of plastic pollution.

Find out more about PET Lamp on catalandeocon.com

MEET THE ARTIST/DESIGNER – Uji ‘Hahan’ Handoko Eko Saputro

Uji Handoko Eko Saputro (aka Hahan) was born in Kebumen, Java, Indonesia, in 1983 and graduated from the Indonesian Institute of the Arts, Yogyakarta, in 2009. Hahan’s work encompasses various forms of media, including sculpture, painting, printmaking and music. It is characterised by a vibrant and chaotic mix of colour, humour and references to music, popular culture, comics and street art – blurring the boundaries between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art to comment on contemporary art, politics and culture.

Hahan is a founding member of Ace House, an artists’ collective based in Yogyakarta. The collective regularly runs a gallery, Ace Mart, that functions as a 24-hour convenience store which sells works of art alongside the usual convenience store items. Ace Mart is an art project that plays with ideas of the global art market and art as a commodity, as well as with the idea of the artist as a producer in these contexts. Hahan also has his own clothing and merchandise line – which, like Ace House , is part of a strategy to make art more accessible.

For the NGV Triennial Hahan has produced an installation called Young speculative wanderers, 2014–15, that looks at art and the art world including artists, collectors and galleries. It consists of three paintings, each supported by a group of figures in a room decorated with patterned tiles and painted walls.

Questions for students

What symbolism or cultural references can you see in the work Young speculative wanderers, 2014 –15?

How might the presentation of the work affect how it is experienced by the audience?

What role does humour play in Hahan’s work?

In what ways does Hahan’s work fit within or challenge our traditional notions of art and art galleries?

Hahan has included the NGV International (St Kilda Road) building in his work. How does he portray the Gallery? What other comments does he make about the world of art?

MEET THE ARTIST/DESIGNER – SHILPA GUPTA

Shilpa Gupta is an Indian artist who lives and works in Mumbai, India. She creates interactive projects, sculptural works and multimedia installations that investigate issues such as politics, changing borders, the environment, globalisation and human rights.

Gupta’s work in the NGV Triennial, Untitled, 2012–15, is a solid mass of microphones rising from the floor in the darkened space, like a massive, humming hive. The work is accompanied by a soundscape of voices and running water and a text that reads:

We look forward towards our past

To the edge of the sea

Waters sink

Oceans flood

Oceans flood

A folded boat risesThe soundscape reflects flows of people through time and place, and Gupta says the gigantic form ‘represents solidified voices, which form a chorus, ready to hurl themselves forward into, and [merge] with, the ocean’.

She says, ‘I use a combination of light and sound and play with the gallery [space] to create an experience for the viewer.’ Each viewer is invited to experience the work subjectively to arrive at their own meaning. Gupta relies on these myriad interpretations: ‘I am generally interested in perception and the translation which takes place – basically, the shift of information from one place to another.’(http://www.sculpture.org/documents/scmag15/sep_15/fullfeature.shtml)

Questions for students

What does the work Untitled, 2012–15 remind you of?

How do the scale of the work and the sound affect the way we experience the work?

What are the cultural elements of Gupta’s work?

In what ways does it transcend cultural borders?

Write your own sound sculpture to describe an issue or idea you would like to bring attention to. Record your work and share it.

MEET THE ARTIST/DESIGNER – Hassan Hajjaj

Hassan Hajjaj is a multidisciplinary artist whose work has embraced film, advertising, photography and graphic design. Born in Morocco in 1961, Hajjaj moved to London in the 1980s. His work mixes music, street culture and design, celebrating individuality and embracing the cultural diversity characteristic of both London and Morocco. In Hajjaj’s photos an array of compelling characters – often friends of the artist – are posed before colourful patterned backdrops. Dressed and styled by Hajjaj, the subjects wear bright clothes that often incorporate fabrics printed with counterfeit brands and logos, purchased in markets in London or Marrakesh. The images are framed in vibrant repeating patterns of found objects such as tins, product labels, plastic construction blocks or tyre rubber. The photographs embrace a Pop–kitsch aesthetic that urges us to celebrate individuality and personal creativity and prompts us to question stereotypes, consumerism and global culture.

Hajjaj also designs interiors. Like his clothes and photographs, these installations are a mix of vibrant textiles and eclectic furnishings, creating a playful atmosphere in which the everyday is treasured and the unique is celebrated. For the NGV Triennial Hajjaj has styled the Gallery Kitchen to re-create the mood of a modern Moroccan tea house, including Moroccan food and music. Custom-designed patterned wallpapers cover the walls and floor and visitors have the opportunity to take their own photographic self-portraits against Hajjaj’s decorative backdrop.

Questions for students

Look closely at the furniture that Hassan Hajjaj has constructed for the Gallery Kitchen. What materials have been used? Why might Hajjaj have chosen these?

What mood has Hajjaj created for the Gallery Kitchen space?

Do a photo shoot that considers costume, character, setting and props. Try to capture the character of your subject by emphasising their traits through props and poses. Make a frame for your portrait that uses labels or products from the sitter’s life.

Design a themed room or corner. Choose a ‘look’ and research which elements are needed to complete that look.

Upcycle found materials to make a new decorative art object – such as a frame, a light shade or a seat, for example.

MEET THE ARTIST/DESIGNER – BEN QUILTY (Analytical frameworks)

Ben Quilty is an Australian artist based in New South Wales. Quilty studied at the Sydney College of the Arts, obtaining a Bachelor of Visual Arts (Painting) in 1994, and at Western Sydney University, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts (Design) in 2002. He also obtained a Certificate in Aboriginal Culture and History. Quilty won the Archibald Prize in 2011, for his portrait of Margaret Olley, and the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize in 2009, for his portrait of Jimmy Barnes. In 2011, Quilty travelled as a war artist to Afghanistan.

VCE ART – ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORKS

Analytical frameworks are a lens through which we can look at works of art and design to give us different perspectives and expand our understanding.

Within the VCE Study Design we use the Structural, Personal, Cultural and Contemporary Frameworks:

The Structural Framework is used to analyse how the style, symbolism and structural elements of artworks contribute to the meanings and messages conveyed.

The Personal Framework is used to discuss how a work of art might reflect the artist’s personal feelings, thinking and life circumstances and how the viewer’s interpretations of the work are influenced by their own life experiences.

The Cultural Framework is used to identify the influence on an artwork of the context of time, place and the society in which it was made.

The Contemporary Framework is used to interpret how contemporary ideas and issues influence the making, interpretation and analysis of artworks from both the past and present.Ben Quilty, High tide mark, 2016

Structural framework

In Ben Quilty’s High Tide Mark, 2016, a single orange life vest hovers in front of a murky background. The vest is inflated with the belt strapped as if in use, but the occupant is missing. Thick sweeps of paint in rich impasto add energy to the vest’s presence. The horizontal lines of the zips and belt divide the image in thirds, like the grinning eyes and mouth of a Halloween mask, while dangling black cords and straps split the painting vertically, adding further structure to the composition.

The vest holds the promise of security and salvation, but the void left by the absent wearer raises uncertainty – did they reach safety? This feeling of apprehension is intensified by the roughly applied paint and sharp contrasts.

Personal framework

In 2011, during the war in Afghanistan, Ben Quilty spent three weeks in Kabul, Kandahar and Tarin Kowt as an official Australian war artist. He witnessed first hand the realities of conflict, and captured the experiences and emotions of Australian servicemen and -women.

In January 2016 Quilty travelled with author Richard Flanagan to Lebanon, Greece and Serbia to witness the refugee crisis in those regions. He describes picking up life jackets strewn across the beach on the Greek island of Lesbos, the stepping-off point for those arriving in Europe:

I picked up the vest that became the subject for High tide mark from the beach at Lesbos. I filled my bag up with broken vests that first day and have brought many more home since then. Each one has been worn and discarded. When the people land from the ocean they are told that they are safe and that they have reached Europe straight away. There is a sense of massive relief as they climb ashore. Most of them are very wet. Richard and I only witnessed two boats land and it was a very bright sunny day, but very cold. The people pay $1000 for each vest and are not allowed to board the boats without one. In essence, the vests are purchased tickets. There are small vests for kids and big vests for adults. On almost every single one of them a label reads, ‘To be worn by strong swimmers in sheltered waters’. Most Syrians cannot swim and the vests are worn across open ocean, mostly at night. I imagined the vests as knight’s armour, but flawed and functionless.

The single vest, I hope, is like the unknown soldier, a single motif of many, a metaphor for all of the human race, adrift.

By pointing out individual humanity I reckon it’s possible to break through all the crap and get to the core.

(NGV Triennial 2017 Ewan McEoin, Simon Maidment, Megan Patty, Pip Wallis, editors and contributors pp 38)

Cultural framework

The European migrant crisis began in 2015 when large numbers of people began seeking refuge in the European Union (EU) from ongoing conflict in countries in Western Asia, South Asia and Africa – with the greatest exodus from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. The number of forcibly displaced people in the world today – more than 60 million – is at the highest level since the Second World War.

The EU has struggled to cope with the influx of new arrivals. Border control, deaths at sea, immigration detention and refugee settlement are political and humanitarian issues on a massive scale.

The life jackets distributed to asylum seekers as they make the perilous water crossing to Europe are often of inferior quality and of little use in preserving life in dangerous conditions. This is emblematic of contemporary mass manufacturing, where lower production costs and higher profits come at the cost of human safety.

Despite its geographical isolation, Australia is not immune from the effects of global conflict. Issues such as border protection, immigration and migrant detention are subjects of ongoing political debate. The avoidance of deaths at sea is used as an argument for stringent immigration quotas and border control measures.

In Australia, a country girt by sea, the life jacket is a potent symbol of these issues.

Contemporary framework

Ben Quilty uses his art and his profile as an artist to draw attention to a contemporary issue, highlighting the role of the artist as a social commentator and an advocate for those without a voice. In this work Quilty focuses on the plight of the individual in relation to global issues that are often depersonalised or sensationalised for political expedience. In doing so, he draws attention to the human impact of global politics.

By using traditional techniques – paint on canvas – in such an expressive way he emphasises his presence as the artist, and humanises an issue that has become less potent because it is so frequently seen in the media.

Questions for students

Structural framework

How is colour used in this image to create impact?

What effect is created by the rough application of paint?

What are some of the other choices made by Quilty in this work? What is the result?Find out about more about Ben Quilty as war artist here

Personal Framework

How is Quilty’s personal experience evident in his work?

What personal associations does this image hold for you as the viewer?

How does your own experience impact your interpretation of the work?Cultural framework

How does knowledge of news and current affairs influence your understanding of this work?

How might this work be viewed by an asylum seeker? How might you view it if you had no knowledge of the context in which it was created?Contemporary framework

In what ways does this work reinforce or challenge traditional notions of art?

How might this work challenge or reinforce traditional notions of the role of the artist?

Compare High tide mark, 2016 to other works in the Triennial that deal with similar issues of displacement: Richard Mosse, Incoming, Candice Breitz, Love story, for example. Which work is, in your opinion, the most effective in communicating a message?MEET THE ARTIST/DESIGNER – PAE WHITE

Pae White (born 1963) is an American artist who currently lives and works in Los Angeles, California. Since 2004 Pae White has produced large scale tapestries that highlight the details of everyday materials: fabric swatches, junk mail, advertising, wrapping paper. White photographs the objects, creating a digital image which is then reproduced by artisans – machine-loomed into a woven form. Her Triennial work Spearmint to Peppermint 2013 is an enormous silver-green foil wrapper, crumpled into a topography of folds and creases to form a grand abstract tapestry. What appears to be a shimmering metallic surface reveals itself to be threads and fibres on closer inspection.

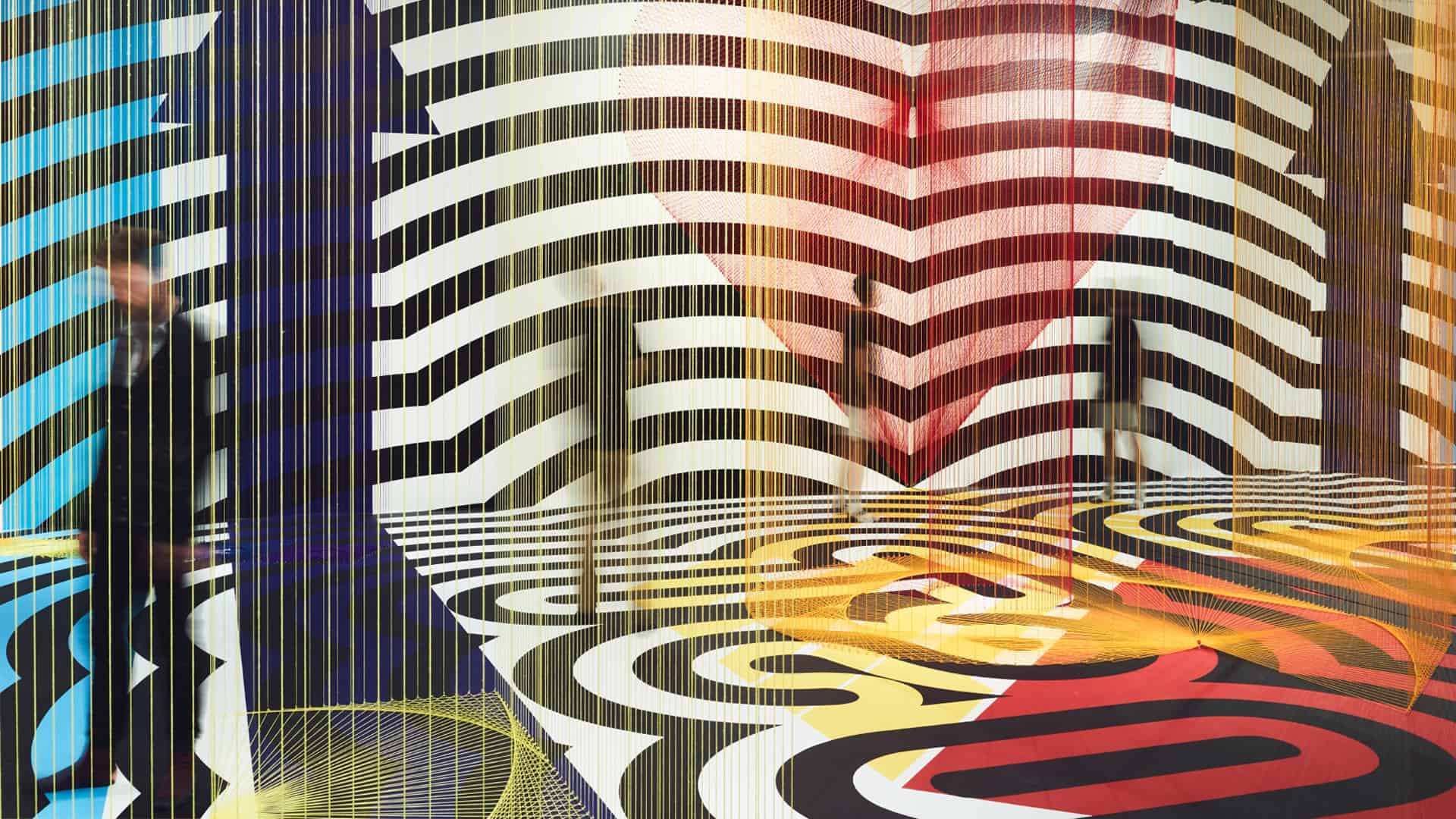

Pae White’s work Untitled 2017 is an immersive installation inspired by the graphic design for the 1968 Olympics, held in Mexico City. The Olympic design – which incorporated the text ‘Mexico 68’ in a rounded font with strong black and white parallel lines along with the Olympic rings – was intended to recall the patterns of the Huichole Indians of Mexico. In Untitled 2017 the viewer negotiates the maze of super graphics, bright threads and mirrors, becoming a part of the installation as they pass through it.

Questions for students

List the materials and techniques used in Pae White’s works Spearmint to Peppermint 2013 and Untitled 2017.

How is scale important in White’s work?

How are the man-made and the machine-made contrasted in Pae White’s work?

How does each of Pae White’s works play with illusion and our perception of space?

In what ways do Pae White’s works challenge our perceptions and expectations?

What is the role of the viewer in each of the works?

Resources